Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Across the developing world some women still walk miles each day in order to fetch fresh water for their families. Building wells, to reduce the risk of waterborne illness and give women back their time, is therefore a popular project among development agencies. Yet these seemingly useful initiatives can sometimes fail.

During the war in Afghanistan, US marines found that one newly built village well had been destroyed — not by insurgents but by the women for whom it was built. Why? The daily walk for water was the women’s only chance to escape home life. Their action illuminates a simple but often forgotten point about policymaking: what is true in one place is not necessarily true in all.

Ceteris paribus — all else being equal — is a popular principle in the study of social science. By assessing the partial impact of one variable upon another, practitioners can develop causal theories. Sometimes, however, this can encourage blinkered thinking.

The appeal of causal models lies in their simplicity. Rule of thumb is often preferred to convoluted explanations. Emphasis is placed on theories that pitch schools of thought against one another, Keynesianism versus Monetarism, for example.

But the real world is a complex system full of feedback loops, reverse causality and tipping points. Ceteris paribus is an essential tool for controlled studies, but in an evolving economic, technological or social environment, following the principle of mutatis mutandis — changing what needs to be changed — is essential.

There are a number of reasons for this. First, relied-upon theories often break down. Take central bankers’ focus on the Phillips curve (the theoretical negative relationship between inflation and unemployment). In Europe, joblessness is tame despite falling inflation. Other factors must be at play. One explanation is that as supply-chain shocks unwound, price pressures dropped but companies, concerned about the post-pandemic availability of workers, decided to hoard labour.

Second, theories can result in unintended consequences. One example is the attempt by the US to decouple itself from China. Raising import barriers should reduce the direct flow of goods from China to America — and it has. But one study suggests the US may still be dependent on China because supply chains have simply been rewired through other countries.

Third, causal relationships may follow theory but not in quite the way that was expected. Bank runs are often triggered by negative news, but before the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank few social scientists factored in how social media might expedite that process. The spread of information on X, coupled with the ease of digital banking, contributed to faster-than-anticipated depositor outflows.

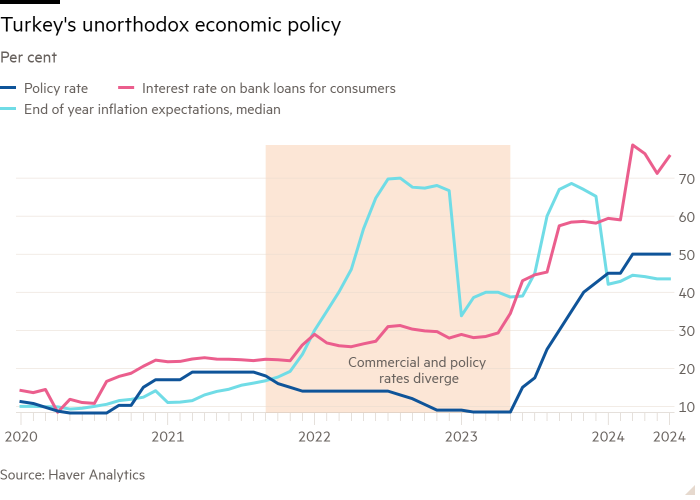

There is another example of this in Turkey. In late 2021, the central bank was pressured by the president to cut interest rates despite high inflation. Price growth surged, as expected. But in early 2023 it dropped. Some economists were surprised that inflation did not spiral further. One explanation is that despite low official interest rates, private lenders kept their own rates high in anticipation of uncontrollable inflation. This helped to maintain credit discipline, taming prices.

Some observers adopt a cynical view that such complexity means policymakers cannot control or model anything and ought to focus on simple interventions that do no harm. Then again, this is what well-builders in Afghanistan thought they were doing. Even simple interventions can have unexpected consequences.

There are established public policy frameworks, from regulations to taxation and spending, that influence norms and incentives in a broadly predictable manner. Policymakers just need to remember that all solutions must be considered as part of a system.

That means encouraging small-scale policy experiments, drawing on multidisciplinary expertise and using granular and more real-time data. Maja Göpel, a political economist, is hopeful that technology might help. “The digital revolution — sensors, imagery, digital twins, data processing, pattern recognition and automated processes — can play a decisive role in connecting assumptions about economic agents and best policy options with real-world developments,” she says.

Over the past few centuries, economics and the social sciences have helped us to simplify the world into rules, relationships and trends. But their utility over the coming decades is going to be determined by how well they can capture complexity.