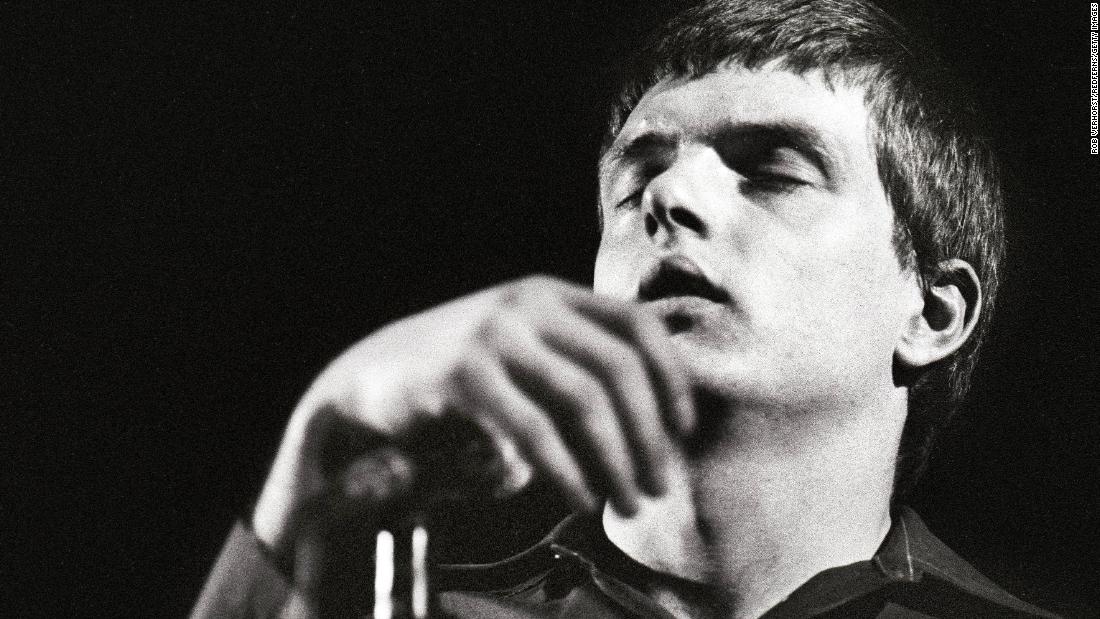

After battling epilepsy and depression, Curtis died on May 18, 1980. He was just 23 years old.

In the years since his death, Curtis’ bandmates Bernard Sumner and Stephen Morris have sought to pay tribute to his life, both through the music of New Order — the later reincarnation of their band — and now by raising awareness about suicide prevention.

Both men spoke to CNN to discuss the legacy of their friend and to reflect on the signs that they didn’t pick up on regarding his struggles.

Curtis’ lyrics partially reflected his real-life torment — one that wasn’t always visible, according to Sumner.

“The thing was that there was two personas, there was the Ian that hung out with us and was a good laugh and had lots and lots of fun. And then there was the persona that was expressed through his lyrics and they were, you know, poles apart, really, the two didn’t add up, and it was confusing,” Sumner said.

Morris said he regrets that he was only able to pick up on the significance of what Curtis had been writing about after he had passed.

“Ian’s lyrics were great, you were very lucky to have someone who wrote such fantastic lyrics, but we thought, ‘that’s really clever, he’s writing about somebody else, it’s great how he can get in the mind of another person.’ And then after his death, you look at it and think, ‘oh, it was all about him,'” he said.

Towards the end of his life, Morris and Sumner said they tried to use music to help Curtis as they began to register that he was struggling.

“We wrote two songs, I think, two weeks before Ian died to try and heal him through music,” Sumner said.

One song was “Ceremony,” Sumner said, describing it as their attempt to get Curtis “involved in the band and involved in music and remind him of what … a great future he had.”

“Unfortunately, it didn’t work,” Sumner added.

New Order still performs the song in celebration of Curtis.

On Wednesday, Morris and Sumner participated in an event at the UK Houses of Parliament, in London, to remember Curtis and to promote mental health in collaboration with the charity Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM).

The band wants to raise public awareness and to help increase funding for mental health, particularly for young people, Sumner said.

In the United Kingdom, suicide is the biggest killer of men under the age of 45, causing 18 deaths a day, according to CALM.

“Anything that you can do to stop people taking their own life has got to be a good thing,” Morris said, describing the mental health challenges young people face as a “crisis.”

Despite the figures, Morris said there was a greater awareness of mental health struggles today, compared to when Curtis died.

“In the ’70s, there was a sort of stigma that you didn’t want to admit that there was anything wrong with you. You would be really macho … it was a sign of weakness to say there was something wrong with you.”

“Particularly with young men, you should be able to talk about issues like that, which is one of the big things about mental health these days, young people becoming more aware of it,” Morris said.

While Sumner and Morris regret the premature death of their friend, they say that Curtis has achieved the kind of lasting impact that he had aspired to when he was alive.

“He was like an arrow flying towards the target and the target was to make a mark musically, which he did,” Sumner said.

Morris said the ultimate legacy of Ian Curtis is the fact that the band’s music has helped people around the world.

“When you get people come up to you and say, ‘I just want to thank Joy Division for the music because it’s really helped me through some tough times,’ it says something that there must be something in the music and the lyrics that people could identify with,” he said.