Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

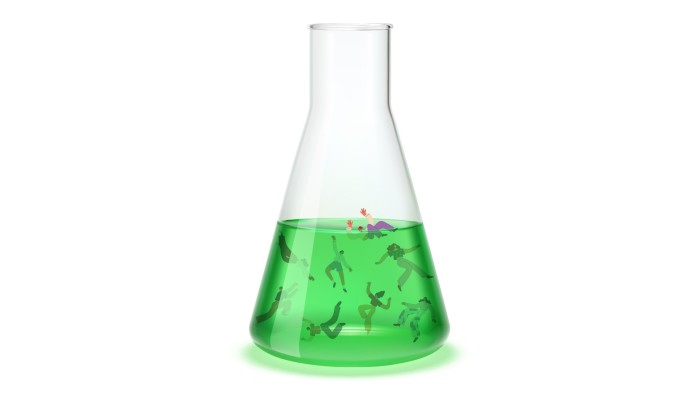

The democratic world is stuck in a self-destructive, self-reinforcing loop: unforced policy errors lead to desperate gambles both by politicians and voters, leading to yet more unforced policy errors. I think it’s safe to say that there is room for improvement. But what might a better path look like?

It sometimes pays to look for a very different perspective, and I’ve found one in an “abbreviated and extemporaneous” lecture given in 1971 to the American Psychological Association, unpublished for many years, and yet even today worth serious attention. That lecture was titled “Methods for the Experimenting Society” and it was given by an academic, Donald T Campbell. It’s partly a manifesto arguing for the use of more rigorous randomised trials in evaluating public policy, but it’s much more than that.

Campbell begins: “The experimenting society will be one which will vigorously try out proposed solutions to recurrent problems, which will make hard-headed and multidimensional evaluations of the outcomes, and which will move on to try other alternatives when evaluation shows one reform to have been ineffective or harmful. We do not have such a society today.”

There’s a lot to explore there. First, that there are some “recurrent” problems that never seem to go away, and yet we should be energetically trying solutions. Campbell calls for a dynamic, can-do attitude, yet recognises that some problems are stubborn. Second, that idea of “hard-headed and multidimensional evaluations”. The phrase suggests that we need serious evidence of success, not just good vibes or empty boasts, but also that rigour shouldn’t mean a blinkered narrowness. Success can come in many forms.

And third, Campbell takes it for granted that many reforms simply won’t work, and we should not hesitate to discard them and try again. Remember, we’re not dealing with the easy stuff here, we’re dealing with the “recurrent problems”. If they were easy to solve they would have been solved already, so we need to be nimble, not dogmatic.

Campbell was a hugely influential thinker in policy evaluation. His name lives on in the Campbell Collaboration, which assembles evidence in social policy, and also in Campbell’s Law, which holds “The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to measure.” When sensible metrics become high-stakes targets, those metrics crack under pressure.

To a certain kind of person, there is something very appealing about the idea of technocrats running randomised trials to discover the best way to run schools or prisons or traffic calming. Campbell was definitely that kind of person, as am I. But Campbell understood that his utopia, his “experimenting society”, had to embody something more fundamental than that. He listed some of the values he had in mind. An experimenting society had to be active, always looking for improvements and practical solutions. It had to be honest, willing to criticise itself and face facts.

It’s striking how different those virtues are from the fearful and polarised habits of today. Populists are temperamentally inclined to dismiss expertise, and Donald Trump, in particular, is unrivalled in his capacity to deny the most straightforward truths about the world.

But neither the Democrats in the US nor the Labour government in the UK have been paragons of open-minded dynamism. The centre left suffer from a brittle arrogance, simultaneously convinced of their superiority yet fearful of attack. That was on display in the Democratic party’s reluctance to challenge a fading Joe Biden until the last possible moment, and their refusal to run a primary process to test out possible successors.

It is also visible in Labour’s timid policy offerings: no serious attempt to find a closer relationship with the EU, and a promise to raise none of the major taxes despite a desperate need for revenue. If they thought the status quo was so terrible, why make such a performance of maintaining it?

One can sympathise. We do not seem to be living in an age that rewards humility, an honest admission of uncertainty or a willingness to change course. But we won’t know for certain until a serious politician gives it a try.

It’s natural to advocate an experimental approach to policy on the grounds of effectiveness: good policy experiments produce results, telling us what works and what doesn’t and allowing us to get better outcomes for less effort. Children learn more, criminals go straight, new drugs cure old diseases. Results matter, but they are not the only reason to aim for an experimenting society. Such a society values curiosity, the childlike sense that the world is full of mysteries to be solved. It values humility, the recognition that nobody has all the answers and that others may know more than we do. It values practical action, the drive to get things done and to solve problems.

In countries gripped by anger and frozen by polarisation, there is not much room for the curious, humble, practical problem solving of the experimenting society. Yet somehow the vicious circle must be broken. “We do not have such a society today,” says Campbell. There is always tomorrow.

Follow @FTMag to find out about our latest stories first and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen