Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

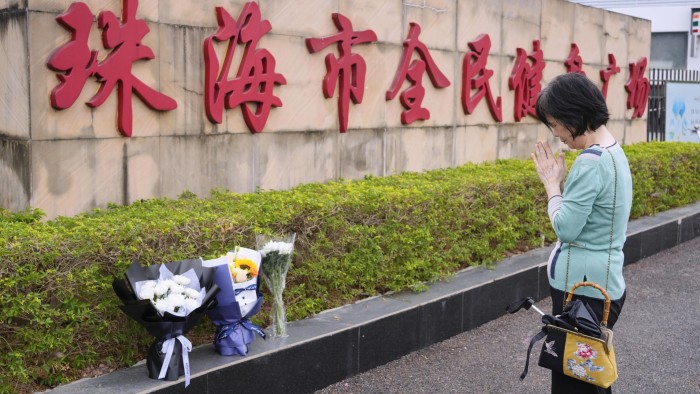

No sooner did mourners place flowers outside the sports centre in the southern Chinese city of Zhuhai, the scene this week of China’s biggest mass killing in a decade, than they were whisked away.

Under police supervision, attendants stuffed the offerings into an office beside the main gate, an apparent effort to downplay the incident in which a man rammed his vehicle into people on Monday, killing 35 and hospitalising 43 more.

“It’s despicable,” said Wang, a hotel restaurant worker who had come to pay his respects of the removal of the tributes.

So shocking was the incident in Zhuhai that it prompted President Xi Jinping to order officials to tighten China’s extensive security networks. All authorities should “strengthen at-source risk prevention and control . . . to protect people’s lives and social stability”, Xi said on Tuesday.

His decree — a rare public statement on an individual crime — signalled the party’s increasing determination to step up forensic monitoring of households and neighbourhoods, as concerns grow about social stability during China’s economic slowdown.

The Zhuhai killings were the latest in a series of mass killings and stabbings this year that have garnered national attention, including two incidents targeting Japanese expatriates.

Analysts suggested economic factors might be partly to blame. Swaths of China’s economy are suffering from a slowdown wrought by a real estate slump that has reduced household wealth and led to job and salary cuts.

“It is a social stability issue,” said Minxin Pei, a political scientist and author of The Sentinel State: Surveillance and the Survival of Dictatorship in China.

Police said on Tuesday that the driver in Zhuhai was a 62-year-old man surnamed Fan, and claimed the incident reflected his unhappiness with the financial settlement from his divorce.

But it took authorities a day following the attack to reveal the death toll, and Pei questioned the police account, saying authorities might have reason to conceal the driver’s motive, particularly if it concerned disputes with local officials.

China officially has low levels of violent crime, but the government does not release clear data on mass murders and similar incidents.

“The government tightly controls information flow, and statistics related to crime — especially those that could potentially portray the country in a negative light — are often subject to strict scrutiny and limited release,” said Shuai Wei, lecturer on social policy and criminology at the University of Liverpool.

Xi has already expanded and strengthened Beijing’s apparatus of social control through grassroots human surveillance of ordinary citizens. As part of this effort, he has embraced the “Fengqiao experience”, a system named for a village in eastern Zhejiang province where, during the Mao Zedong-era, people were re-educated through struggle sessions and public humiliation.

In modern China, the Fengqiao experience refers to the collaboration of ordinary people in monitoring and preventing crime, often through community groups, companies or other local units.

But Pei noted that the party’s surveillance systems were expensive and, after decades of relative prosperity, had yet to be properly stress-tested in times of hardship.

“The system is pretty good at monitoring by my calculations about 1-1.5 per cent of the population,” said Pei, referring to the population that public security officers can feasibly actively monitor and control at any one time. “That’s a lot, but still manageable. But if it gets to about 5 per cent, then the system will really get stressed.”

Authorities have released few details about the attack, and video footage from the event has been removed from online platforms, apparently scrubbed by censors. On Wednesday, police demanded press IDs from media interviewing mourners, and warned them not to talk to journalists.

Residents in Zhuhai said they were shocked by the incident, and that information about it was frustratingly scarce. The city, an affluent manufacturing hub on Guangdong’s border with Macau, rose to prominence as one of the country’s first special economic zones in the 1980s.

Zhang, a retiree in her 50s lingering near a temporary barricade enclosing the site of the attack, said she came to try to learn more about the tragedy, but had been unsuccessful.

“How come [even] the foreign media have come to report about it, but us locals still don’t know the details?” she asked. “It’s really frightening.”

As more people arrived to pay their respects on Wednesday evening, the police presence was reinforced by multiple vans and cars. By nightfall, a team of attendants was working to remove the white flowers and candles placed by mourners.

Wang, a 19-year old Zhuhai resident, said he had come to place a bouquet on behalf of a friend who knew one of the victims. Gazing at the barricades and the empty area at the gates where the flowers once were, he said: “But I don’t really know where to put them.”