This article is an on-site version of Martin Sandbu’s Free Lunch newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every Thursday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

When Donald Trump won the US presidential election in 2016, a debate broke out over whether he owed his victory to economic grievances or cultural resentments, with many right-thinking liberals mocking the economic explanations. There is little trace of that debate today. Most people seem to agree that “economics won it” to bring Trump back to the White House for a non-consecutive second term.

The irony is that nobody believed more strongly in the economic argument than Joe Biden’s White House, which from the start saw its challenge as akin to Franklin D Roosevelt’s — to deliver an economic transformation that restored prosperity to people otherwise tempted by authoritarianism. And they were willing to go against a lot of Democratic establishment orthodoxy in the pursuit of that.

The entire policy agenda of “Bidenomics” was designed to make the American working class feel that the government, and the Democratic party, had their backs: high-pressure labour markets and macroeconomic policy, a strengthened economic safety net, interventionism for industrial renewal, protectionist tariffs and an antitrust policy to rebalance the power between consumers and corporate monopolies.

My doomed prediction for a solid Kamala Harris victory two weeks ago was grounded in a similar view. I thought the Biden White House was — except for the tariffs and protectionism — pursuing policies that made not just economic but also electoral sense. What matters here is not my error of judgment, but how the result makes political decision makers reconsider the merits of a Biden-style economic policy going forward. We could plausibly see the case for an ambitious, economy-reshaping policy discredited for a whole political generation.

So where did the reasoning go wrong?

Was it not “the economy, stupid” after all — in other words, did people not vote based on their economically rooted grievances? Or did they do so, but Bidenomics failed to address those grievances? Or did it address them, but voters still swung away from Biden’s party on economic grounds — and if so, what were they?

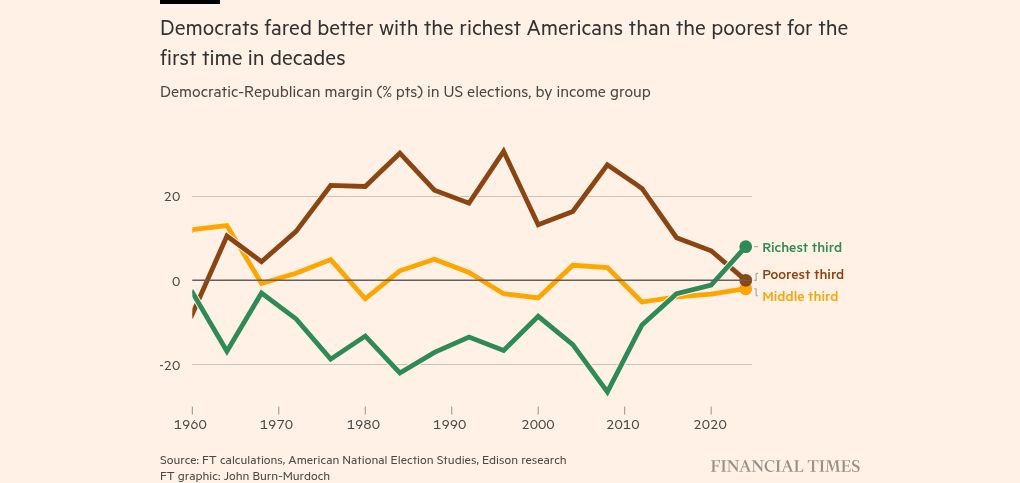

We should be clear about what we need to explain here. It is not that about half of the US electorate chose Trump. That has been true for a decade. It is, rather, why a small but pivotal number of voters added their votes to his count in 2024 — and that this swing was accounted for by the lowest-income voters, across virtually all states, who had already been consistently turning more Republican since 2012. It was this shift (the brown line in the chart below) that the Biden White House and its economic policies had set out to reverse.

As I said, most people seem to think economics mattered a lot, and it was the worst-off who made the swing happen. And, importantly, a lot of people told pollsters and journalists that the economy was one of their main concerns in choosing how to vote — Trump voters in particular. A lot of people said the economy was bad; and the worse they said the economy was, the more likely they were to vote for Trump.

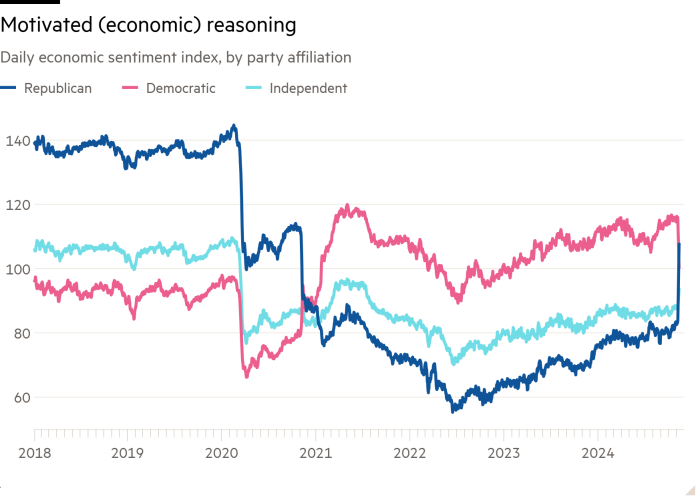

At the same time, people also tell pollsters things like this:

That’s the daily consumer sentiment index from Morning Consult by party political affiliation, which turns out to depend wildly on whether “your” president is in office. This shows that when people tell pollsters what they think about the economy, they may really be telling them about something quite different.

So we cannot simply be satisfied with “what voters tell us”; but we need to make sense of how the economic feelings they report relate to what we can measure separately.

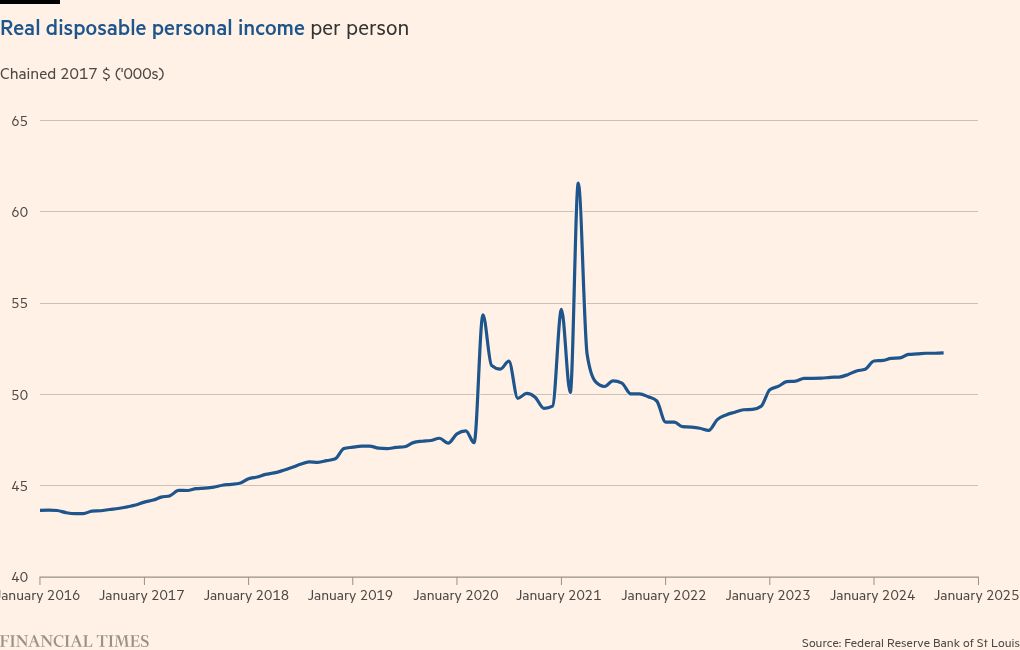

The most common economics thesis of this election is that people were angry about inflation. But inflation peaked in the summer of 2022, and is mostly gone by now. Even more strikingly, probably the best measure of material living standards — real disposable personal income per capita — bottomed out in the same month as inflation peaked, and has been rising strongly ever since. Self-reported economic sentiment, such as the Morning Consult index mentioned above, also bottomed out at the same time, and was at higher levels right before this election than four years ago for most groups including political independents and the lower-paid.

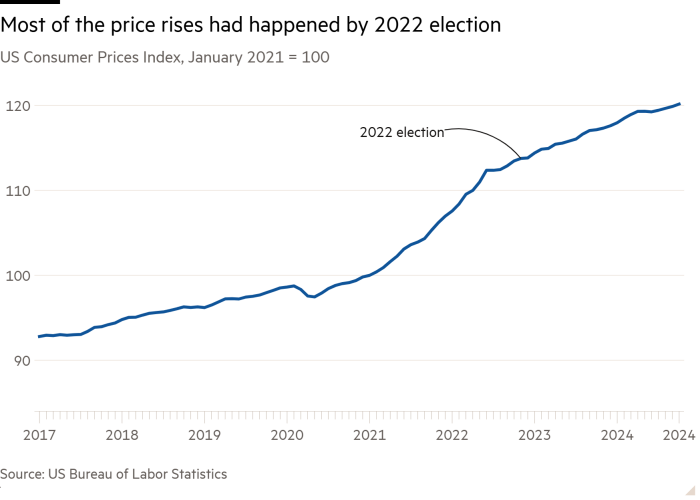

Here is a problem: the Democrats were not punished in the midterm elections in 2022 (or not much — and unlike this year, there were many states where voters swung to Biden’s party that year). So if voters’ anger about inflation drove the election results this year, why were they not at least as angry about it two years ago?

The standard answer is that when voters complain about inflation, they don’t mean what economists mean: it’s the higher level of prices they react to rather than the rate of change. It’s also a common view that people blame the government for high prices and don’t credit it for wage growth. But that’s problematic too: most of the sharp rise in the price level — two-thirds — had already happened by the time of the November 2022 election. And it is surely wage growth people credit the first Trump administration with when they say it was better economically — so why not credit the recent wage growth to Biden?

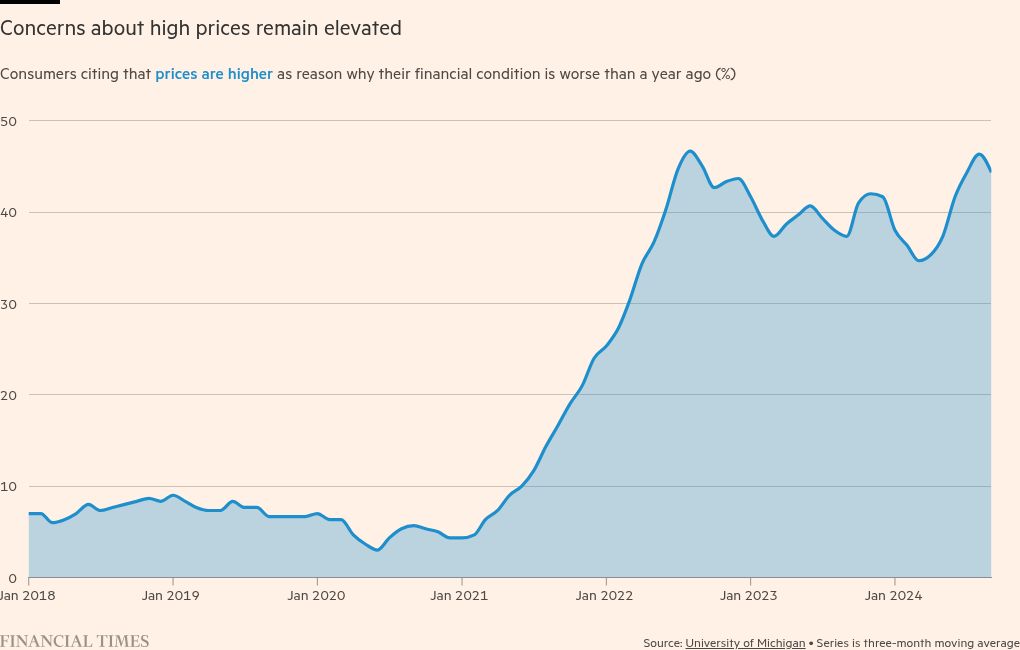

An ad hoc theory can be constructed that it takes time for people to get angry and that the anger, like a radioactive isotope, then has some sort of half-life governing how fast it dissipates. That view has been expressed by the White House economic team. But the evidence is that the higher price levels sank in in no time, as my colleague Joel Suss has pointed out (see his chart below). So we are still stuck with the conundrum of explaining a recent political shift with something that didn’t get worse in the past two years.

Annie Lowrey has long theorised that the real underlying grievance is the overall “unaffordability of American life” which has been going on for a long time. “The economy under Biden looked good but felt bad,” she wrote after the election. That many Americans have poor economic prospects is entirely plausible, and is a good explanation of Trump’s 2016 victory.

But then why did this not benefit Republicans in 2020 and 2022? Lowrey’s answer seems to be that the annoying reminders from the recently more expensive small things (such as groceries and petrol) finally brought home the unaffordability of the big things. But I find it completely implausible that somehow Americans were oblivious to the long-festering cost of living crisis until things were finally getting better.

If it were not for that last point, the “economic voting” story could just be the straw that broke the camel’s back. But many important aspects of Americans’ economic lives — especially of those lower-income groups that swung most strikingly towards Trump — have been improving. That includes people’s self-reported feelings about the economy (such as the Morning Consult survey charted above; despite the strong political partisanship, both Democrats and Republicans show a two-and-a-half-year upwards trend). It also includes their willingness to spend and most importantly real wages, including for the lowest-paid.

It seems incontrovertible that “vibes” have at least something to do with the “economic” vote — that a preference for Trump leads to a negative assessment of the Biden economy as much as the other way round. Insofar as the real economy did drive the Trump swing among the lower-paid, it must involve things that got noticeably worse in the past few years. Here are two.

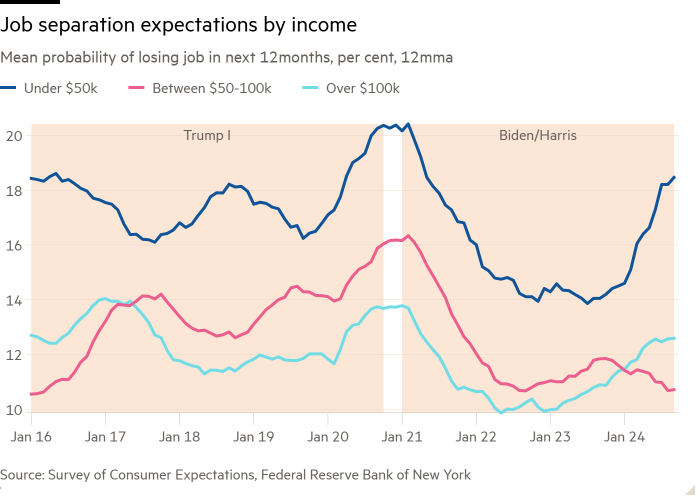

As my colleague Tej Parikh has highlighted (see his chart reproduced below), expectations of job loss rose significantly for the lowest paid in the second half of Biden’s term (and to well below Trump-era levels) after the remarkably strong jobs market of his first half. The lower-paid have also worried more about a rise in the unemployment rate in Biden’s second half than the first half. The employment-to-population ratio, of course, has stagnated for more than a year and started to slip.

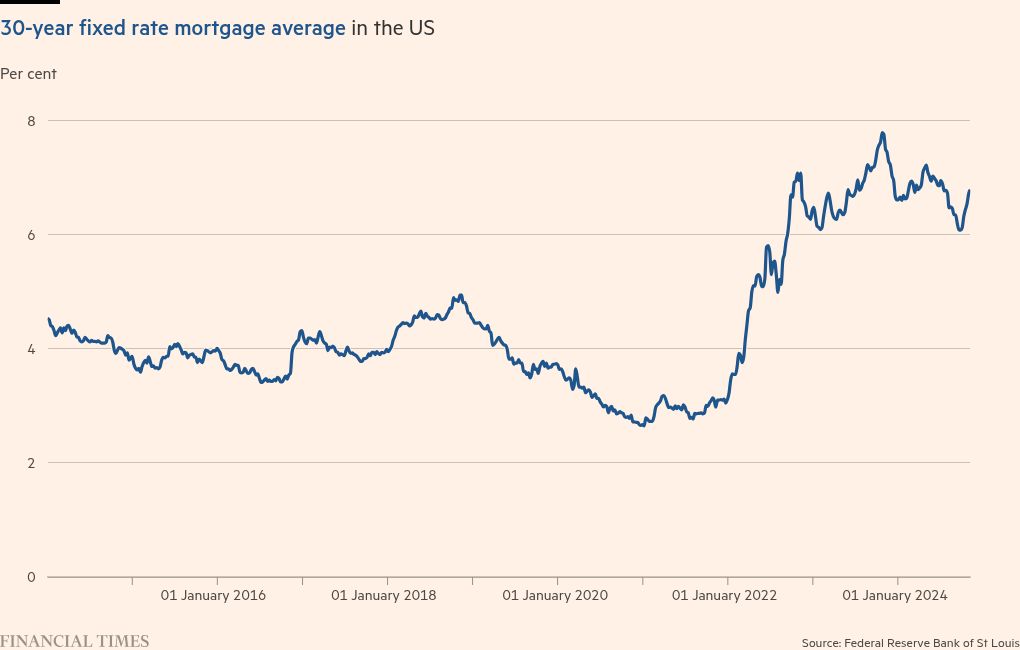

It has also become a lot more expensive to buy a home. In the four years from the start of the pandemic, the monthly cost of a 90 per cent mortgage for the average US home doubled. Some of that was because house prices have risen by just under 40 per cent since Biden took office, of which most had happened by summer 2022. But the 30-year mortgage rate hit an all-time low of 2.65 per cent in the month of Biden’s inauguration and only really started climbing in 2022. By the election that year, it had gone above 7 per cent, and has stayed around that level since.

This affects new buyers, not existing mortgages. So unlike general prices, which hit everyone immediately, the cost of higher interest rates seeped through the economy like a poison from 2022 on, for anyone who bought a new home — or would have liked to but now found it unaffordable. More and more people from late 2022 onwards would come to know of someone suddenly priced out of the housing market.

So how should we think about the electoral failure of the Biden White House’s attempt to emulate Roosevelt? There is nothing here to suggest that the policies themselves were not the right ones. They did not lead to electoral punishment when the economy was at its worst, and they did produce an objective economic improvement and indeed an improvement in economic sentiment.

Two largely uncomfortable conclusions emerge. First, more than inflation itself putting people off Bidenomics — let alone Biden’s actual policies — it was the Federal Reserve’s response to it that created economic unhappiness, by doubling housing costs and ending the strong jobs market. Politically speaking, the cure may have been worse than the disease. And, second, “vibeonomics” undermined economics: those voters tempted by populist economic promises were not being sold Biden’s effective economic populism hard enough to shift the vibes.

Could anything have changed this? Who knows. But I find myself thinking that if there was little the Biden administration should have changed in terms of economic policy (apart from less gratuitous protectionism), then it ought to have doubled down on selling its economic message electorally. Note that Harris did better in the polls (for what they were worth) while emphasising prices and what she would do to bring them down. As that message faded — at the behest of the corporate establishment in her entourage, according to The Atlantic’s Franklin Foer — she fell back in the polls. And economic arguments were never her strong suit.

The Democrats had a good economic story to tell, but one that wasn’t as good as it could have been and, above all, they didn’t tell it loudly enough. In hindsight, my mistake was to miss that. If I had seen it in time, my conclusion would have been that the Democrats should have doubled down on both the economic substance and the message. But it’s too late to know if that would have worked.

Other readables

Recommended newsletters for you

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Your essential guide to money, interest rates, inflation and what central banks are thinking. Sign up here

Unhedged — Robert Armstrong dissects the most important market trends and discusses how Wall Street’s best minds respond to them. Sign up here