Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

To think that two and two are four / And neither five nor three / The heart of man has long been sore / And long ‘tis like to be. A.E. Housman.

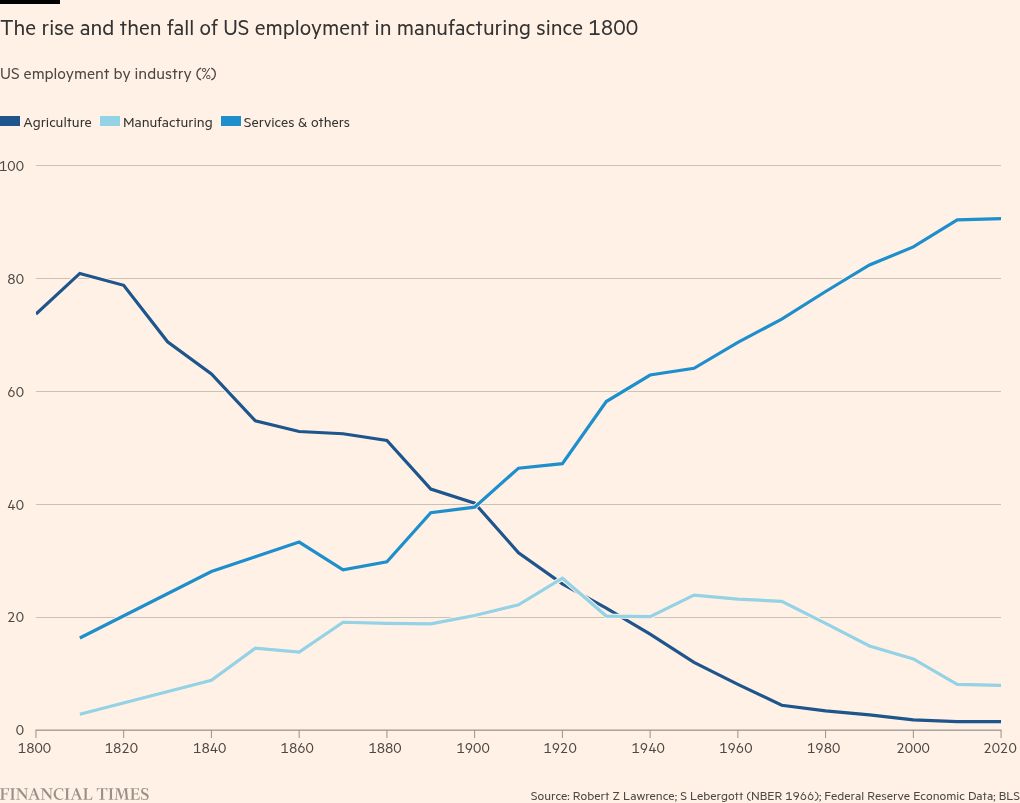

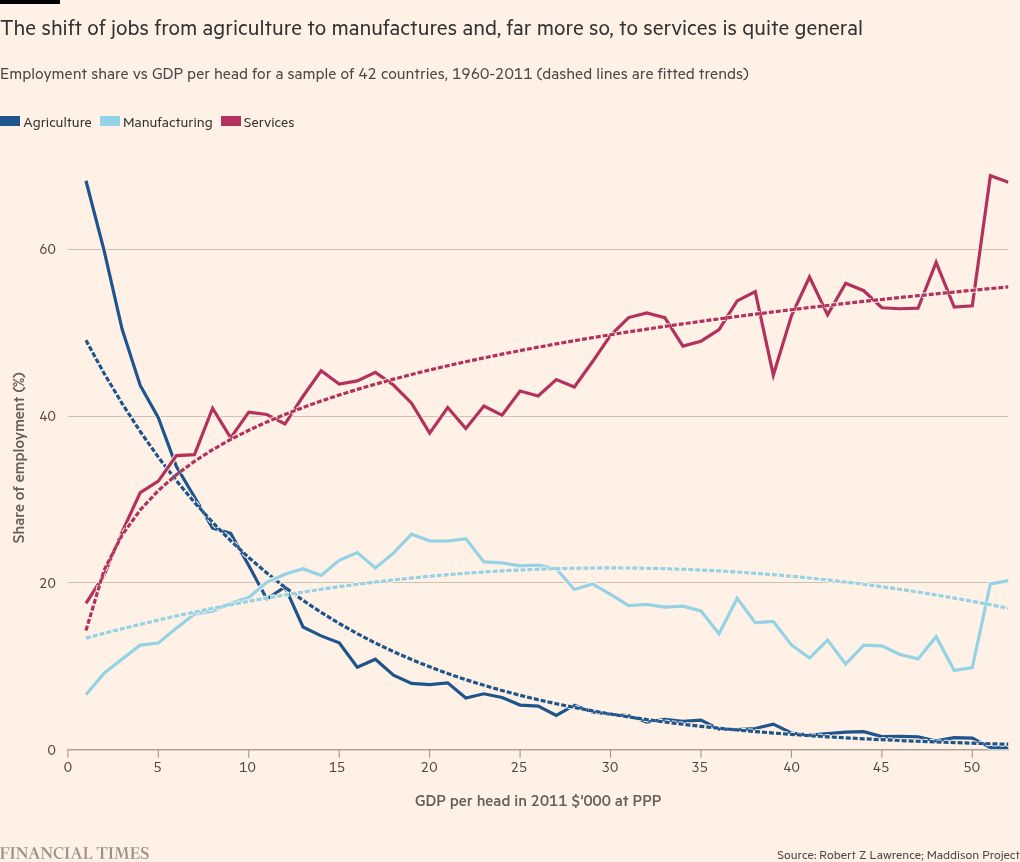

In 1810, 81 per cent of the US labour force worked in agriculture, 3 per cent worked in manufacturing and 16 per cent worked in services. By 1950, the share of agriculture had fallen to 12 per cent, the share of manufacturing had peaked, at 24 per cent, and the share of services had reached 64 per cent. By 2020, the employment shares of these three sectors reached under 2 per cent, 8 per cent and 91 per cent, respectively. The evolution of these shares describes the employment pattern of modern economic growth. It is broadly what happens as countries become richer, whether they are big or small or run trade surpluses or deficits. It is an iron economic law.

What drives this evolution? In Behind the Curve — Can Manufacturing Still Provide Inclusive Growth?, Robert Lawrence of Harvard’s Kennedy School and the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) explains it in terms of a few numbers — the initial shares of employment in each of the three sectors, “income elasticities of demand” for their products, their “elasticities of substitution” and relative rates of growth of productivity. Income elasticities measure the proportional increase in demand for a category of goods or services relative to income. Elasticities of substitution measure the impact of changes in price on demand. A crucial consequence of the simple model that emerges is “spillovers”: what happens to a sector also depends hugely on what happens in the other sectors.

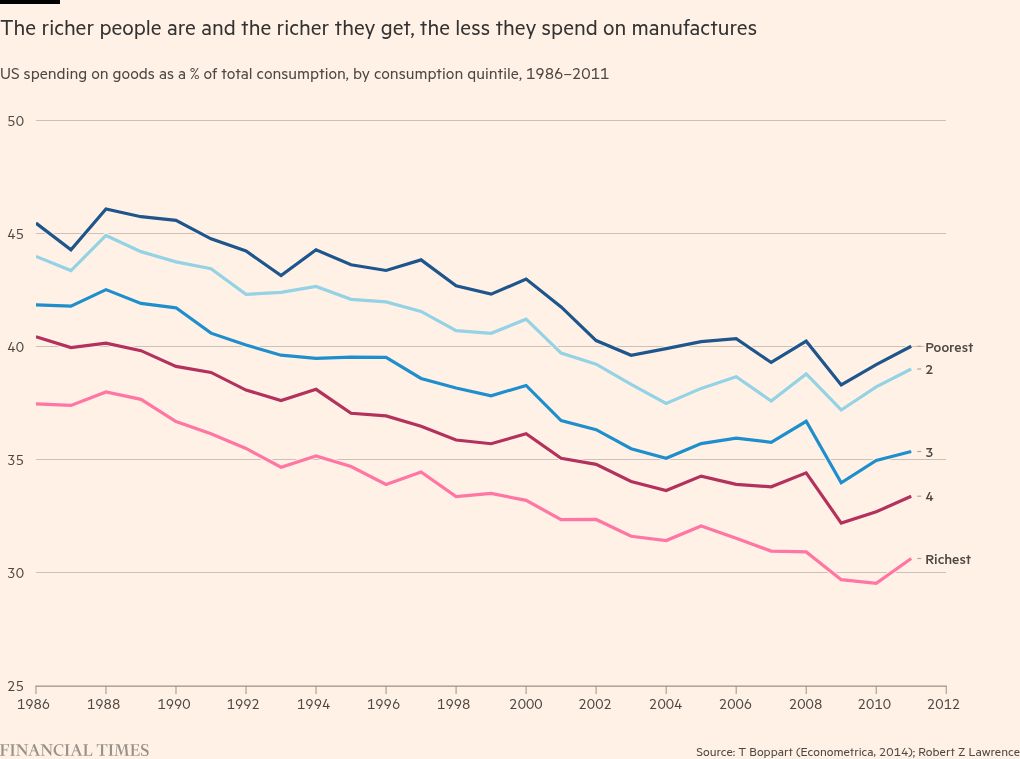

Now make the following simple and empirically-based assumptions. First, productivity grows fastest in agriculture, followed by manufacturing and then services. Second, income elasticities of demand are below one for agriculture, but above one for manufactures and still higher for services. Third, elasticities of substitution are all below one. This means that the proportion of income spent on a given broad category declines as it becomes relatively cheaper. Assume, too, that economies have all started with similar proportions of workers in the three sectors to those of the US in the early 19th century.

What happens is the pattern seen in the US and other contemporary high-income countries (except city-states, where food was partly imported from outside). Initially, two positive forces — cheaper food and higher incomes — shift spending towards manufactures and drive up the share of manufacturing in employment. But two negative forces — the decline in prices of manufactures relative to services and the higher income elasticity of demand for the latter — do the reverse. Initially, the positive effects on manufacturing dominate, because the agricultural revolution is so huge. Yet there comes a time when agriculture is too small to provide a positive impulse to manufacturing. Then forces operating within manufacturing and the service sector dominate. Employment shares in manufacturing start to fall. In the US, these have been falling for seven decades. The idea that this process is reversible is ridiculous. Water flows downhill for a good reason.

In manufacturing, tasks are repetitive and must be done precisely in a controlled environment. This is perfect for robots. The overwhelming probability then is that in a few decades nobody will work on a production line. In some ways, that is a pity. But the work was also dehumanising. Surely, we can do better than hanker nostalgically for this inescapably vanishing past.

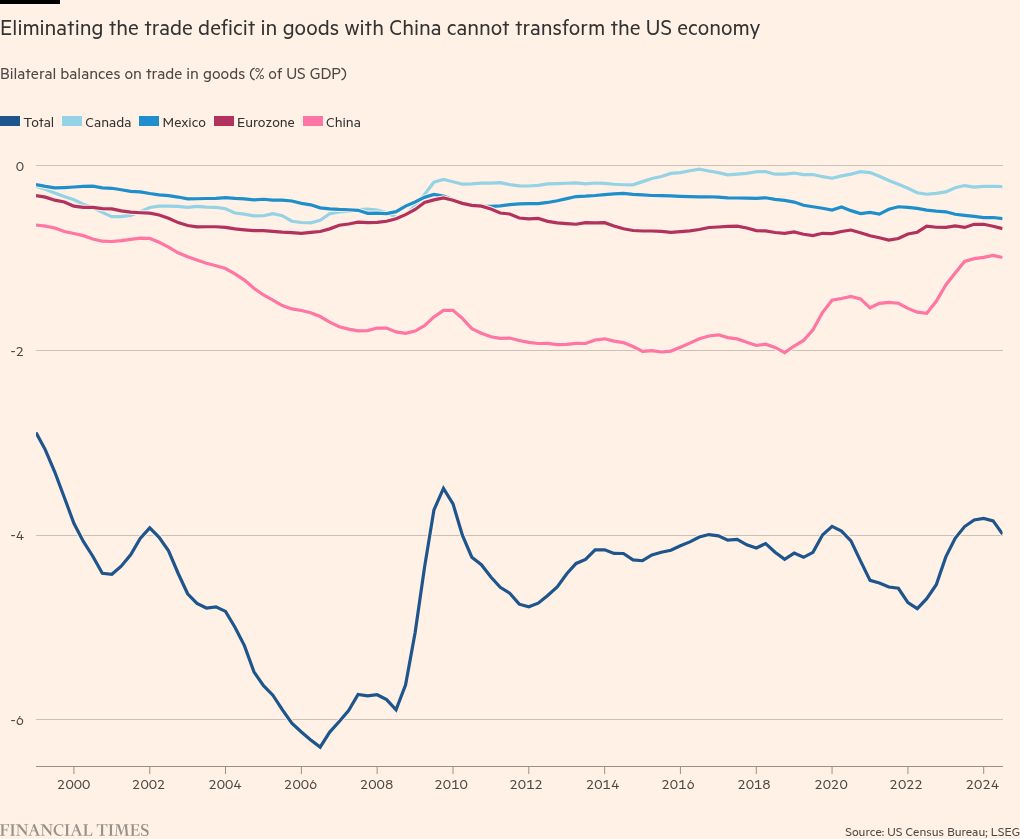

Humans seek to blame someone for events beyond anybody’s control. It is so much easier to blame the disappearance of US manufacturing jobs on China than on domestic consumers and automation. The bilateral US trade deficit in goods with China is only 1 per cent of GDP. The overall US deficit in goods has been around 4 per cent of GDP since just after the 2008 financial crisis. If that were eliminated (probably impossible, given US competitiveness in services and the macroeconomic forces causing US trade deficits), it would indeed increase domestic output of goods (presumably at the expense of services). But the very most it is likely to do is to bring employment shares to the levels of a decade or two ago.

In fact, as Lawrence shows in another paper for the PIIE, “Is the United States undergoing a manufacturing renaissance that will boost the middle class?”, even Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act merely delivered a further “steady decline in the manufacturing employment share of non-farm employment”. Trump’s tariffs will probably deliver no more than this. After all, rich Asian countries with trade surpluses in manufactures also have falling shares of jobs in that sector.

This is not to argue that there are no important issues in production and trade in manufactures. Some manufactures are indeed vital to national security. The ability to produce some manufactures may also generate important externalities for the economy. Even so, the idea that these are manifestly more important than in other sectors — software, for example — is nonsense. Equally, as the structure of the economy shifts, people need help in developing new skills. The absence of a market in the creation of human capital is a market failure that justifies intervention.

Fetishising manufacturing cannot restore the old labour force. Worse, the Trump tariffs will not only fail to achieve that goal, but will cause further malign side-effects. Not least, they will create a clash between the effects of the tariffs, the intended expulsion of millions of illegal immigrants and the planned tax cuts. The consequences for political and economic stability will be the subject of next week’s column.

Follow Martin Wolf with myFT and on Twitter