Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

How did the polls in the US fare over the past week? This may sound like a simple question, but depending on what you’re actually asking, your chosen yardstick and possibly even your fundamental beliefs about the human psyche, there are half a dozen equally legitimate answers.

Let’s start with the basics. At the national level, the polling average on election eve had vice-president Kamala Harris winning the popular vote by around one and a half percentage points. At the time of writing, Donald Trump is on course to win by that same margin, for a combined miss of around three points. This is a smaller error than four years ago, and almost bang on the long-term average.

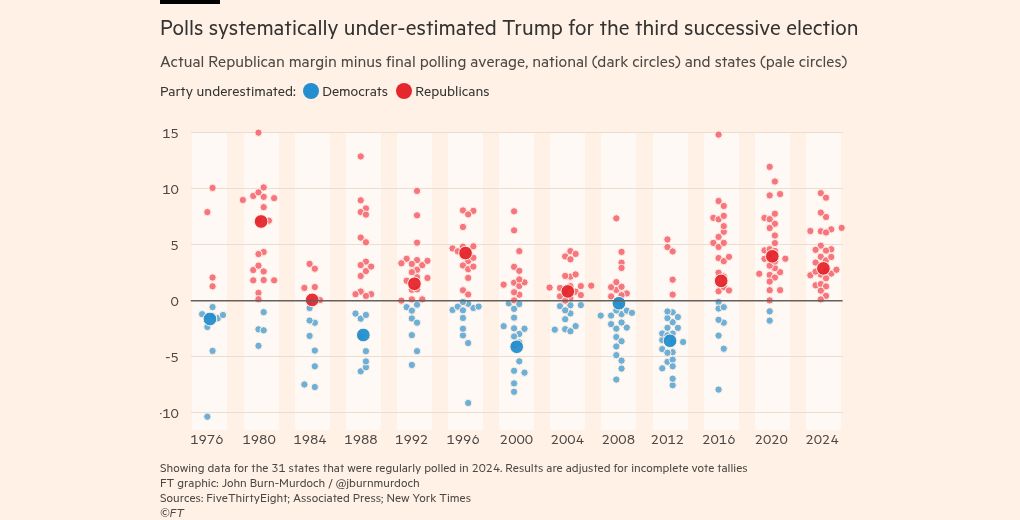

At the state level, the polls were on average closer to the outcome this year than in either 2016 or 2020. However, for the first time in 50 years of public polling, the average survey in every single state underestimated the same candidate — Trump.

But the thing is, these same statistics provoke wildly different reactions in different people. For the average left-leaning American who had spent weeks staring at a blue number that was marginally higher than a red number, Tuesday’s results were earth shattering proof that polling is broken. The three-point miss might as well have been 20 points.

But from the perspective of pollsters, political scientists and statisticians, the polls performed relatively well. The misses, both at national and state level, were all well within the margin of error, and the fact that the polls were no worse at capturing the views of Trump states than of deep blue ones — a marked contrast to 2016 and 2020 — suggests the methodological refinements of recent years have worked.

If your temptation is to scoff at that last paragraph, let me offer you this: Google searches in the US for terms like “why were the polls wrong” peaked far higher last week and in 2016 than they did in 2020, despite the fact that the polls underestimated Trump by even more in 2020.

The reason is fairly obvious, but it has nothing to do with statistics or polling methodology. The human brain is much more comfortable with binaries than probabilities, so a close miss that upturns the viewer’s world stings much more than a wider miss that doesn’t.

But I don’t mean to let the industry completely off the hook, and to that end there are two separate issues that need to be addressed.

The most obvious is that although the polls fared slightly better this year, this was still the third successive underestimation of Trump. The methodological tweaks that pollsters have made since 2016 have clearly helped, but the basic problem remains. Whether due to new sources of bias introduced by these tweaks, or to further shifts in the rates at which different types of people answer surveys, pollsters appear to be walking down the up escalator.

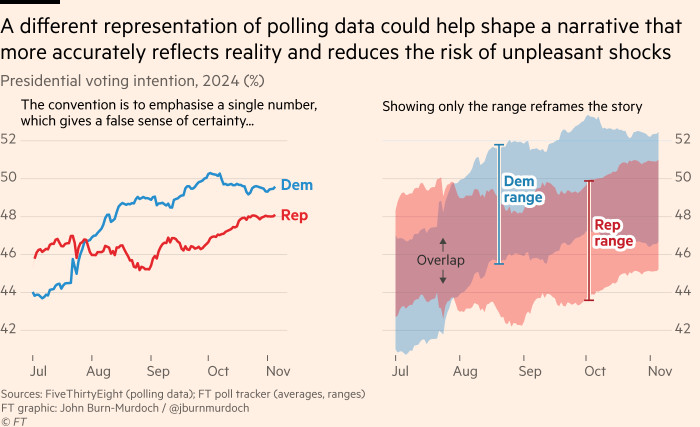

The second is a more fundamental issue with how the numbers are presented. It’s true that pollsters and polling aggregators have been giving loud and clear warnings for weeks about how a very narrow margin in the polls not only could, but quite likely, would still see one side or the other win decisively. But such a proliferation of health warnings raises the question of whether polls, polling averages and their coverage in the media are doing more harm than good.

Let’s say that you the pollster and I the journalist know that the true margin of error in a poll is at best plus-or-minus three points per candidate — that is, a poll with candidate A leading by two points is not inconsistent with that candidate losing by four on election day even if the poll was perfect. And suppose that we also know that humans instinctively dislike uncertainty and will fixate on any concrete information. Then who is served when we highlight only a single number?

If we want to minimise the risk of nasty shocks for large portions of society, and we want pollsters to get a fair hearing when the results are in, both sides need to accept that polls deal in fuzzy ranges, not hard numbers.