A Montreal university shut down a think-tank devoted to studying genocide, citing financial strain and a lack of academic impact, but some human rights advocates say it’s making a mistake.

The Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies (MIGS), closed last week, when Concordia University, which funded it, said it was “concluding” the institute’s operations.

While Concordia said the decision was largely financial, in a statement a spokesperson for the university also referenced the work of the think-tank and the academics associated with it.

“The work of researchers and faculty was different from the projects taken on by MIGS,” the spokesperson wrote.

‘Concordia’s loss’

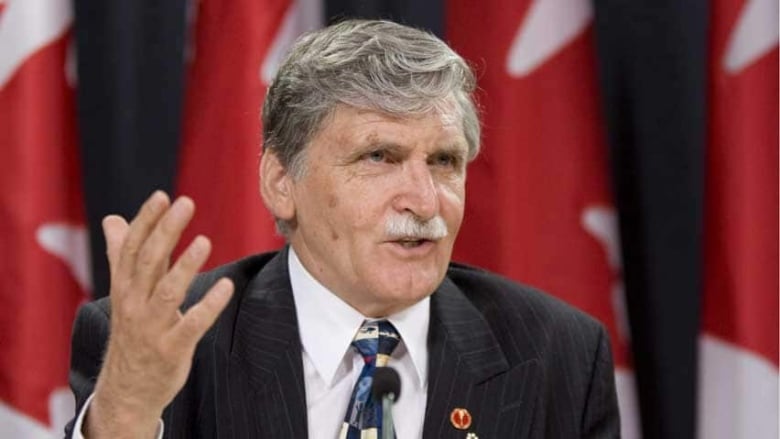

The statement reflected a view that was prevalent inside the university, according to Romeo Dallaire, a former Canadian senator and retired lieutenant-general who is known for his work advocating against mass atrocities around the world, and was a senior fellow with MIGS.

The university undervalued MIGS’s work, he said, in part because it wasn’t an academic institution and wasn’t involved in producing research.

“It wasn’t recognized as a significant asset to the university’s persona in the international sphere on human rights. They based that on research publications versus articles and engagement at home and in international bodies,” he said.

“So, fine, that’s one position.”

But MIGS did provide opportunities to students to take part in its work, he said. It also regularly hosted talks and summits. Kyle Matthews, the executive director of MIGS, attended conferences around the world and appeared in media interviews.

That work was important, Dallaire said. He argued that MIGS’s advocacy work was vital in bringing attention to published research — which he said universities often struggle to do.

Now, it will be “Concordia’s loss” that MIGS will no longer be affiliated with the university, Dallaire said, suggesting the institute could continue to operate on its own or may become affiliated with another university.

Concordia is facing financial headwinds. This year, it approved a $34.5-million budgetary deficit, in large part due to the Quebec government’s changes to the tuition fee structure for out-of-province and international students.

It’s unclear how much money the university will save by closing MIGS. Two employees lost their jobs, including Matthews. The institute also had a budget to finance its activities, which included some money to have Dallaire come and speak to students.

John Packer, the director of the Human Rights Research and Education Centre at the University of Ottawa, said MIGS gave Concordia credibility among international think-tanks.

He said the decision to close the institution was “baffling,” particularly at a time when interest in human rights issues is growing.

“Genocides, unfortunately, are multiplying, it seems, around the world,” he said. “But not only genocide. Atrocity, crimes — all kinds of related issues. In this context, MIGS was, I’d call it, a small jewel and a precious jewel. One we had to value.”

David Donat Cattin, an adjunct associate professor of international law at the New York University (NYU) Center for Global Affairs, who was also a senior fellow with MIGS, said he appreciated the institute’s ability to assemble experts on international relations and human rights.

He described the institute as a small but flexible operation and said he volunteered his time to work with MIGS.

“I didn’t co-operate with them for the money,” he said. “They were able to put together very interesting programs at very cost-effective value and I understood they had their own donors.… For me it was a bit surprising that they would shut down a think-tank that had a big impact.”

In a statement, Matthews said he was proud of his work with MIGS and said the decision to leave Concordia was not his to make. He highlighted the institute’s advocacy work, mentorship work with students and its efforts to counter hate speech.