The blowout victory of Donald Trump and the Republican party on Tuesday night will lead to major changes in important policy areas, from immigration to Ukraine. But the significance of the election extends way beyond these specific issues, and represents a decisive rejection by American voters of liberalism and the particular way that the understanding of a “free society” has evolved since the 1980s.

When Trump was first elected in 2016, it was easy to believe that this event was an aberration. He was running against a weak opponent who didn’t take him seriously, and in any case Trump didn’t win the popular vote. When Biden won the White House four years later, it seemed as if things had snapped back to normal after a disastrous one-term presidency.

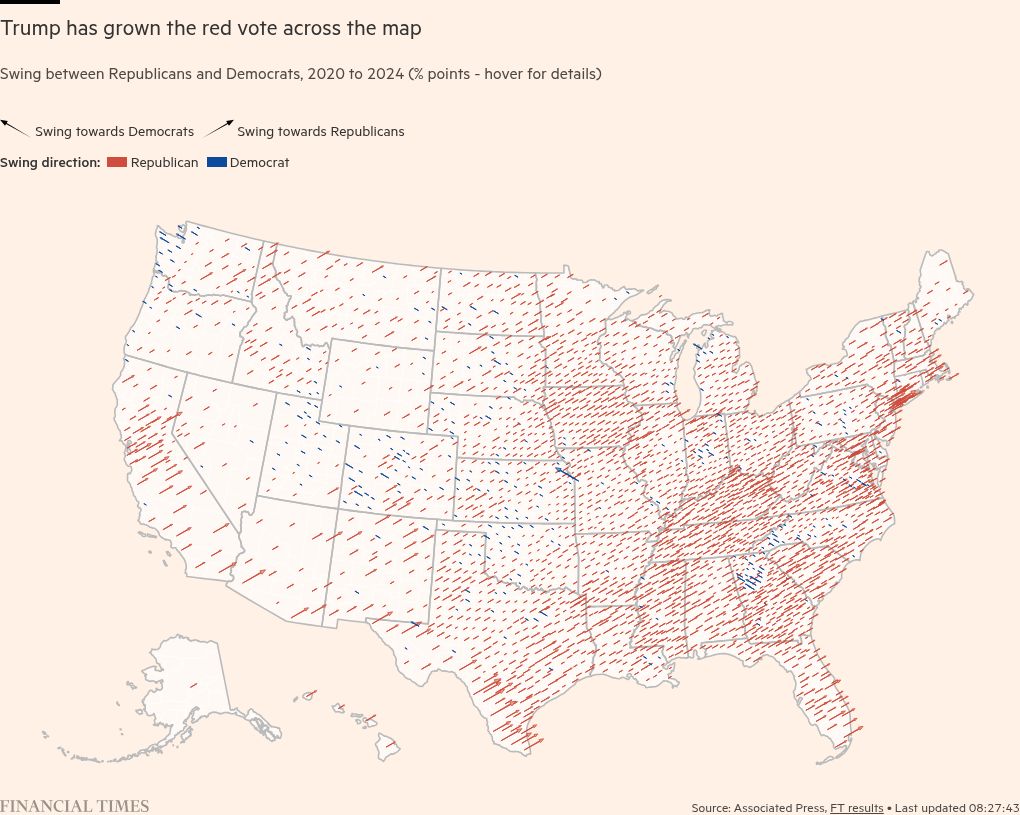

Following Tuesday’s vote, it now seems that it was the Biden presidency that was the anomaly, and that Trump is inaugurating a new era in US politics and perhaps for the world as a whole. Americans were voting with full knowledge of who Trump was and what he represented. Not only did he win a majority of votes and is projected to take every single swing state, but the Republicans retook the Senate and look like holding on to the House of Representatives. Given their existing dominance of the Supreme Court, they are now set to hold all the major branches of government.

But what is the underlying nature of this new phase of American history?

Classical liberalism is a doctrine built around respect for the equal dignity of individuals through a rule of law that protects their rights, and through constitutional checks on the state’s ability to interfere with those rights. But over the past half century that basic impulse underwent two great distortions. The first was the rise of “neoliberalism”, an economic doctrine that sanctified markets and reduced the ability of governments to protect those hurt by economic change. The world got a lot richer in the aggregate, while the working class lost jobs and opportunity. Power shifted away from the places that hosted the original industrial revolution to Asia and other parts of the developing world.

The second distortion was the rise of identity politics or what one might call “woke liberalism”, in which progressive concern for the working class was replaced by targeted protections for a narrower set of marginalised groups: racial minorities, immigrants, sexual minorities and the like. State power was increasingly used not in the service of impartial justice, but rather to promote specific social outcomes for these groups.

In the meantime, labour markets were shifting into an information economy. In a world in which most workers sat in front of a computer screen rather than lifted heavy objects off factory floors, women experienced a more equal footing. This transformed power within households and led to the perception of a seemingly constant celebration of female achievement.

The rise of these distorted understandings of liberalism drove a major shift in the social basis of political power. The working class felt that leftwing political parties were no longer defending their interests, and began voting for parties of the right. Thus the Democrats lost touch with their working-class base and became a party dominated by educated urban professionals. The former chose to vote Republican. In Europe, Communist party voters in France and Italy defected to Marine Le Pen and Giorgia Meloni.

All of these groups were unhappy with a free-trade system that eliminated their livelihoods even as it created a new class of super-rich, and were unhappy as well with progressive parties that seemingly cared more for foreigners and the environment than their own condition.

These big sociological changes were reflected in voting patterns on Tuesday. The Republican victory was built around white working-class voters, but Trump succeeded in peeling off significantly more Black and Hispanic working-class voters compared with the 2020 election. This was especially true of the male voters within these groups. For them, class mattered more than race or ethnicity. There is no particular reason why a working-class Latino, for example, should be particularly attracted to a woke liberalism that favours recent undocumented immigrants and focuses on advancing the interests of women.

It is also clear that the vast majority of working-class voters simply did not care about the threat to the liberal order, both domestic and international, posed specifically by Trump.

Donald Trump not only wants to roll back neoliberalism and woke liberalism, but is a major threat to classical liberalism itself. This threat is visible across any number of policy issues; a new Trump presidency will not look anything like his first term. The real question at this point is not the malignity of his intentions, but rather his ability to actually carry out what he threatens. Many voters simply don’t take his rhetoric seriously, while mainstream Republicans argue that the checks and balances of the American system will prevent him from doing his worst. This is a mistake: we should take his stated intentions very seriously.

Trump is a self-proclaimed protectionist, who says that “tariff” is the most beautiful word in the English language. He has proposed 10 or 20 per cent tariffs against all goods produced abroad, by friends and enemies alike, and does not need the authority of Congress to do so.

As a large number of economists have pointed out, this level of protectionism will have extremely negative effects on inflation, productivity and employment. It will be hugely disruptive of supply chains, which will lead domestic producers to request exemptions from what amount to heavy taxes. This then provides the opportunity for high levels of corruption and favouritism as companies rush to get on the president’s good side. Tariffs on this level also invite equally massive retaliation by other countries, setting up a situation in which trade (and therefore incomes) collapse. Perhaps Trump will back off in the face of this; he may also respond as former Argentine president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner did by corrupting the statistical agency reporting the bad news.

With regard to immigration, Trump no longer simply wants to close the border; he wants to deport as many of the 11mn undocumented immigrants already in the country as possible. Administratively, this is such a huge task that it will require years of investment in the infrastructure needed to carry it out — detention centres, immigration control agents, courts and so on.

It will have devastating effects on any number of industries that rely on immigrant labour, particularly construction and agriculture. It will also be monumentally challenging in moral terms, as parents are taken away from their citizen children, and would set the scene for civil conflict, since many of the undocumented live in blue jurisdictions that will do what they can to prevent Trump from getting his way.

With regard to the rule of law, Trump during this campaign has been singularly focused on seeking revenge for the injustices he believes he has suffered at the hands of his critics. He has vowed to use the justice system to go after everyone from Liz Cheney and Joe Biden to former Joint Chiefs of Staff chair Mark Milley and Barack Obama. He wants to silence media critics by taking away their licences or imposing penalties on them.

Whether Trump will have the power to do any of this is uncertain: the court system was one of the most resilient barriers to his excesses during his first term. But the Republicans have been working steadily to insert sympathetic justices into the system, such as Judge Aileen Cannon in Florida, who threw out the strong classified documents case against him.

Some of the most important changes will come in foreign policy and in the nature of the international order. Ukraine is by far the biggest loser; its military struggle against Russia was flagging even before the election, and Trump can force it to settle on Russia’s terms by withholding weapons, as the Republican House did for six months last winter. Trump has privately threatened to pull out of Nato, but even if he doesn’t, he can gravely weaken the alliance by failing to follow through on its Article 5 mutual defence guarantee. There are no European champions that can take the place of America as the alliance’s leader, so its future ability to stand up to Russia and China is in grave doubt. On the contrary, Trump’s victory will inspire other European populists such as the Alternative for Germany and the National Rally in France.

East Asian allies and friends of the US are in no better position. While Trump has talked tough on China, he also greatly admires Xi Jinping for the latter’s strongman characteristics, and might be willing to make a deal with him over Taiwan. Trump seems congenitally averse to the use of military power and is easily manipulated, but one exception may be the Middle East, where he is likely to be wholeheartedly supportive of Benjamin Netanyahu’s wars against Hamas, Hizbollah and Iran.

There are strong reasons for thinking that Trump will be much more effective in accomplishing this agenda than he was during his first term. He and the Republicans have recognised that policy implementation is all about personnel. When he was first elected in 2016, he did not come into office surrounded by a coterie of policy aides; rather, he had to rely on establishment Republicans.

In many cases, they blocked, deflected or slow-walked his orders. At the end of his term, he issued an executive order creating a new “Schedule F” that would strip all federal workers of their job protections and allow him to fire any bureaucrat he wanted. A revival of Schedule F is at the core of the plans for a second Trump term, and conservatives have been busy compiling lists of potential officials whose main qualification is personal loyalty to Trump. This is why he is more likely to carry out his plans this time around.

Prior to the election, critics including Kamala Harris accused Trump of being a fascist. This was misguided insofar as he was not about to implement a totalitarian regime in the US. Rather, there would be a gradual decay of liberal institutions, much as occurred in Hungary after Viktor Orbán’s return to power in 2010.

This decay has already started, and Trump has done substantial damage. He has deepened an already substantial polarisation within society, and turned the US from a high-trust to a low-trust society; he has demonised the government and weakened belief that it represents the collective interests of Americans; he has coarsened political rhetoric and given permission for overt expressions of bigotry and misogyny; and he has convinced a majority of Republicans that his predecessor was an illegitimate president who stole the 2020 election.

The breadth of the Republican victory, extending from the presidency to the Senate and probably to the House of Representatives as well, will be interpreted as a strong political mandate confirming these ideas and allowing Trump to act as he pleases. We can only hope that some of the remaining institutional guardrails will remain in place as he takes office. But it may be that things will have to get a lot worse before they get better.

Francis Fukuyama is a senior fellow at Stanford’s Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law, and author most recently of ‘Liberalism and Its Discontents’

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen