America’s traditional allies in Europe and east Asia — not to mention its enemies — are all too aware that Donald Trump wants to keep them guessing over his plans. Yet on some issues his aides say he is crystal clear.

They insist that he will be ready to act with vertiginous speed to end the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East. All the while, he plans to threaten ever-higher tariffs to push America’s allies to spend more on defence and to equalise their trading relationship with the US — while also maintaining pressure on China.

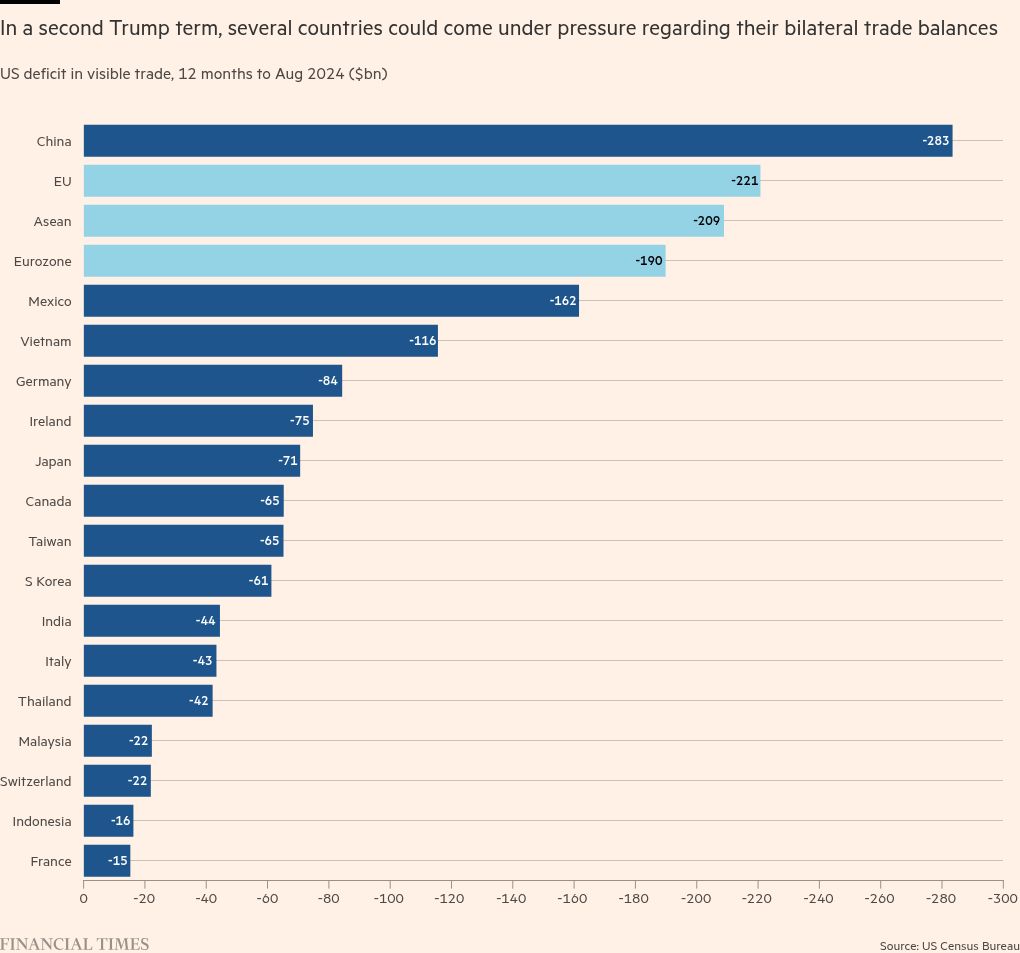

The audacious “America first” global agenda envisaged by Trump’s allies, advisers and former — and would-be future — aides, is one in which friends and foes alike will be judged by the same simple metric: their bilateral trading surplus with the US.

“It’s not a matter of whether you’re an ally or an adversary; if you’re a trading partner with us, you need to be trading in reciprocal terms,” says Senator Bill Hagerty, who was ambassador to Japan in Trump’s first term and is a potential cabinet office-holder in a second.

“He was looking for reciprocity the entirety of his time in office and he has discussed this with me: it’s going to take something dramatic to get the attention of the countries we trade with.”

Trump’s opponents say much of this prospectus is hubristic and rash. In the view of many mainstream economists it is economically illiterate. Officials around the world see it as airbrushing the complexities he will face. But they also concede that the inward-looking focus of Trump’s first term has suffused not just Republican but also Democratic thinking on America’s role in the world.

On one subject, most of America’s allies have little doubt: that they will have a turbulent relationship with the second Trump White House. They have noted how many of the establishment foreign policy figures from his first term have distanced themselves from their former boss, and in some cases, given excoriating accounts of his administration.

Trump’s confidants say America’s allies are right to be jittery. “Predictability is a terrible thing,” says Ric Grenell, a hard-charging ally of Trump who is tipped for an important role. “Of course the other side [America’s enemies] wants predictability. Trump is not predictable and we Americans like it.”

Trump’s foreign policy intimates bridle at Democrats’ accusation that they are isolationist, a term with uncomfortable echoes of the 1930s. They insist they would if needed deploy America’s military power, but selectively rather than reflexively. As for alliances, they say they believe in them but that America’s partners need to pull their weight more.

“I wrote speeches for secretaries of defence 20 years ago begging our partners to step up,” says Mike Waltz, one of the foremost Republican speakers on national security in the House of Representatives. “Collectively, Nato can take more of a share of this defensive burden. If they are not going to now, when are they?”

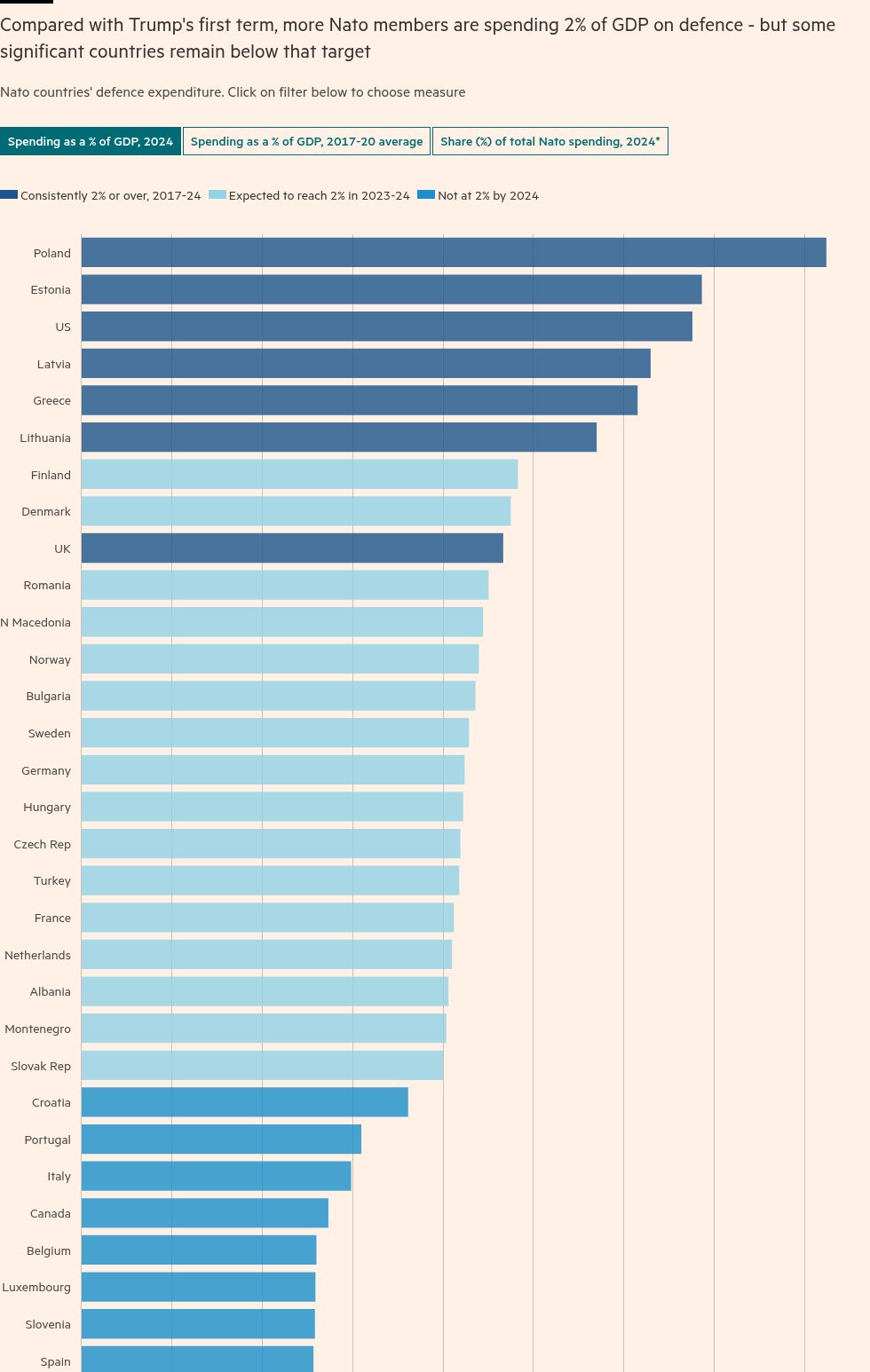

After pressure in Trump’s first term, Nato members and east Asian allies have increased the share of their budget spent on defence. As of June, 23 of Nato’s 32 members had met its target of spending 2 per cent of GDP on defence, twice as many as four years ago. But in a second Trump term they are set to face pressure to do more.

Nato’s members “patted themselves on the back” prematurely, Waltz says, at its summit in July. “Do you pat the student on the head when they go from an F to a D? We should be at 100 per cent minimum of members hitting 2 per cent, and celebrating those who are contributing three or four per cent.”

Germany and France, two of Europe’s largest economies, both of which have recently hit the 2 per cent mark, could face particular pressure over both defence spending and their bilateral trade surpluses with America.

“I think it’s going to be rocky for them, and for Nato members not paying the 2 per cent. It’s a big deal for Trump,” says Fred Fleitz, a former CIA analyst who served in Trump’s White House and is now at the America First Policy Institute Center for American Security. Fleitz, who caveats his remarks by saying he does not speak for Trump and does not know his foreign policy plans, believes that energy security, trade balances and protecting supply lines would be priorities in the second term.

Building on the protectionism of his first term, Trump has threatened a sweeping new tariff regime, including 20 per cent on all imports, up to 60 per cent on Chinese imports, and the possibility of swingeing increases on other unspecified targets. An “across-the-board” tariff is “entirely possible”, says Senator Hagerty, without carve-outs for individual countries.

In such a testing scenario, many allies believe bilateral relationships will be paramount rather than the alliance networks expanded by the Biden administration. Elbridge Colby, a Pentagon aide in Trump’s first term, who also makes clear he does not speak for the campaign, suggests the second Trump administration could be “pro-alliances, but a different approach to alliances.” He singles out Poland, South Korea, India and Israel as models of this kind of ally “who are self-reliant, capable and willing to do things for shared interests, even if they do not always agree with us”.

FT Edit

This article was featured in FT Edit, a daily selection of eight stories to inform, inspire and delight, free to read for 30 days. Explore FT Edit here ➼

As for multilateralism, that is likely to drift further to the margins of policymaking. Grenell, who was an outspoken ambassador to Berlin and a Balkans envoy in Trump’s first term, argues that America’s west European allies are “trapped” in an outdated way of thinking, looking to the UN Security Council for multilateral solutions. “We like coalitions of the willing,” he says.

“The UN can be important but it isn’t the only tool, and sometimes it’s not that useful. We would rather form coalitions with people who want to get stuff done.”

Trump and his vice-presidential running mate, JD Vance, have spoken repeatedly of their desire to end the war in Ukraine. The question is how. A rare insight came in September when Vance outlined the idea of a frozen conflict, with autonomous regions either side of a demilitarised zone — and Kyiv in diplomatic limbo, outside Nato.

A blueprint, one long-term Trump adviser says, could be a reimagining of the failed Minsk agreements of 2014 and 2015, which sought to end the fighting in eastern Ukraine between Ukrainian forces and separatists of the Russian-speaking minority backed by Moscow. These pacts outlined a plan that kept Ukraine’s territorial integrity while enshrining autonomous zones, but the terms were never implemented or enforced.

This time around, the adviser says, there are likely to be enforcement mechanisms with consequences for breaching the deal. However, it would have to be policed by European troops, not Nato forces or UN peacekeepers, he argues. “There are two things America will insist on. We will not have any men or women in the enforcement mechanism. We’re not paying for it. Europe is paying for it.”

Kyiv argues that a settlement without stiff security guarantees for Ukraine would be tantamount to surrender to Vladimir Putin, as it could give the Russian leader a breather to prepare for a fresh assault, and risks sending a sign of weakness around the world. It could also lead to a split in Europe; some Nato members might diverge over how to respond if America steps away.

Trump’s allies argue that Ukraine is losing the war, and so pushing for a settlement is morally right; that he believes Biden should have talked to Putin, just as presidents spoke to Soviet leaders in the cold war; and that Nato membership for Ukraine is not an option in the short term.

Fleitz, who served in Trump’s first administration, says that membership could be taken off the table for a number of years to get Russia to negotiate. “We freeze the conflict, Ukraine does not cede any territory, they don’t give up their territorial claims, and we have negotiations with the understanding there probably won’t be a final agreement until Putin leaves the stage,” he says.

Such an approach, however, would not have uniform support within the Republican party. While in thrall to Trump, the party has three national security groupings competing for his ear, according to the European Council on Foreign Relations: “restrainers”, essentially America Firsters; “prioritisers” who want to focus on China; and “primacists”, old-school believers in projecting American power across the world who have a strong caucus in the Senate. The first two are united in wanting to all but leave Ukraine to Europe.

Colby, who sees himself as a prioritiser, rejects the argument that a deal would embolden Beijing. “They are not patiently waiting to be taught a moral tale from what’s happening thousands of miles away,” he says. “They are going to look at the balance of forces in Asia and our resolve there. If anything, it’s more in their interest to have Russia weakened in a long-running war and so becoming more dependent on China.”

America has only so much “shield power”, he adds, arguing it has to be deployed in the best way to avoid a war with China, “and that’s Asia”.

As for how to force Putin to negotiate if he thinks his forces are on a roll, Waltz suggests Trump could threaten to crash Russia’s economy by lowering the price of oil and gas. “The president very much understands leverage and we have tremendous economic leverage on Russia,” he says. “The first step would be, in his words: ‘drill, baby, drill’. You flood the world with cheaper, cleaner American oil and gas. You drive down the price.”

Saudi Arabia, an important ally of Trump’s in his first term, would not welcome such a move. But people close to Trump insist he is likely to exert powerful economic leverage on Putin. They tout the Abraham Accords, the agreements signed between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan, in Trump’s first term, as evidence of his peacemaking routine.

“He has shown he knows how to bring both sides to the table,” says Grenell. “He’s done it consistently. Arabs and Israelis, Russians and Ukrainians will be next.”

Late in September Trump strode into a hotel ballroom in Washington DC to deliver a blistering speech to the Israeli American Council. If his Democratic opponent Kamala Harris became president, he declared, Israel would “not exist within two years”.

The apocalyptic language was aimed at trying to win over the Jewish vote, by signalling he will be an even stronger supporter of Israel than President Joe Biden. But while Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu clearly hoped for a Trump victory, the strength of their relationship has fluctuated. People close to Trump insist he would not flinch from pressurising Netanyahu if he felt the time was right to push for a settlement.

“President Trump can bifurcate Israel from Netanyahu,” says Grenell. “He can be critical of leadership decisions while maintaining support for a country’s right to defend themselves.”

One scenario is that Trump will swiftly invite Netanyahu to Washington to push for a ceasefire leading to the return of the hostages taken by Hamas. “Then you can say to the Israelis: ‘Now, knock it off. We’re done. And we’re going to go to a peace agreement,’” says the veteran adviser.

How Netanyahu would respond to such a scenario is open to question, but Trump is keen to return to the idea of a grand bargain with Israel and Saudi Arabia for long-term regional peace.

Trump is also likely to step up pressure on Israel’s old enemy, Iran. In his first term he pulled America out of the 2015 Iran nuclear accord. Fleitz believes he will make clear that nations that violate American-led sanctions would face secondary sanctions. “The objective should be to bankrupt Iran again and to reinstitute maximum pressure,” Fleitz says.

But for all Trump’s hawkish record on Tehran, it is unclear he would favour a war with Iran. “Overall, he has a huge aversion to conflict,” says a senior European diplomat in Washington. “In this he is not dissimilar to Biden.”

After the November 5 election, a pivotal question is how Trump will resolve the divergence between hawks in his party who talk of a new cold war with China, and his own instincts to apply economic leverage and do deals with Beijing.

“China is an existential threat to the US with the most rapid military build-up since the 1930s,” says Waltz. “China’s navy is larger than ours. We have to make significant investments in our own readiness.”

But he adds that, in his dealings with Trump, the former president argues China needs America more than America needs them. “He talks much more about trade deals, tariffs and currency than about what we do in a conflict in the Taiwan Strait,” says Waltz. “He believes we apply economic strength in a way backed by robust military presence that can prevent these wars.”

For Taiwan, this is an unnerving time. Trump has made clear he expects it to spend more on defence. “It is spending more compared to a few years ago, but they have to do more,” says Heino Klinck, a former senior Pentagon official in Trump’s first term.

East Asian allies can expect to be assessed by how they are aiding regional security, says Klinck. “We are not the US of yesteryear. We do not have the resources we once had.”

Trump has even mused that Taiwan cannot take America’s support for granted if Beijing orders an invasion. However, his supporters say that ultimately he will pursue maximum deterrence to dissuade China from attacking Taiwan. “Xi Jinping knows if he takes any aggressive action, Donald Trump would deliver real consequences,” says Hagerty.

China policy has, in fact, seen rare common ground between Trump and Biden. On taking office, both imposed tariffs on China to protect America’s strategic industries. The principal difference has been over the scale and focus of sanctions. Trump is threatening a more scattergun regime than Biden’s. In such a scenario, Europe would find itself caught in the middle, and Trump would expect it to join America in raising tariffs on Chinese exports.

“We need Europeans to be clear-eyed about China,” says Grenell. “Many in Europe missed the warning signs from Putin and now they have a massive war on their hands. We’ve been begging the Europeans to see communist China for what they are doing.”

As ever with a new administration, much will depend on the senior appointments and the power balance in Congress. International officials who are anxious about Trump hope the inconsistency and cabinet turmoil which slowed the agenda in his first term may hobble the second term too.

Not so, say his allies. “President Trump realises he is only going to have four years, so the time is limited,” says Hagerty. “If he wants to put us on even terms with other countries, he’s going to have to take dramatic steps.”

Additional reporting by Felicia Schwartz, Alex Rogers and James Politi

Data visualisation by Keith Fray

This story was updated after the November 5 US election