French premier Michel Barnier has sought to make his belt-tightening budget more palatable by arguing that it requires everyone to share the burden to address a national deficit crisis.

Yet politicians from across the spectrum have jumped to the defence of one particular category of the population, asking for it to be spared: France’s 17mn retirees.

Barnier only floated a modest cut to pensions next year by proposing a six-month delay to an annual inflation adjustment, which would save €3.6bn on the roughly €380bn spent on benefits to retirees.

Far-right leader Marine Le Pen likened the move to “stealing billions from our elderly”, while a lawmaker in Barnier’s own camp called it “a bad way to save on public spending”.

The backlash to even such modest changes highlights how fraught the topic of any changes to the pension system remains in France, where President Emmanuel Macron defied mass protests last year to raise the retirement age from 62 to 64.

But economists and analysts say that if France is to address its structural deficit, it will have to tackle pensions given that they are the biggest single spending line — about one-quarter of the annual budget.

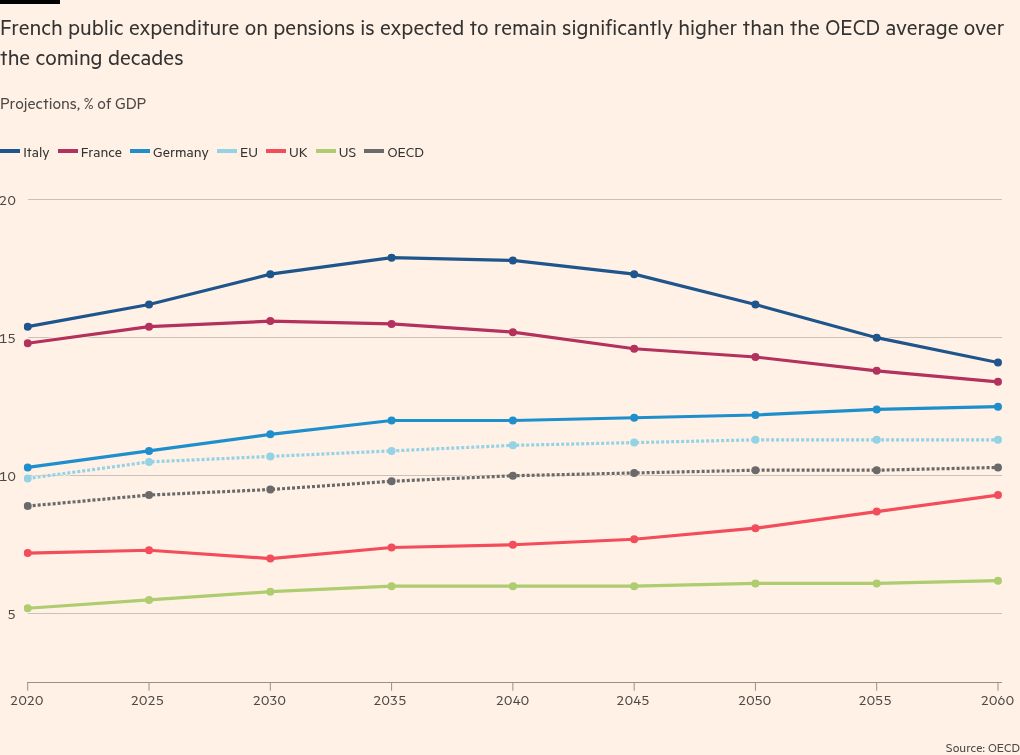

French pensions are funded through workers’ payroll taxes that at almost 28 per cent of gross income are about 10 points higher than the OECD average. The country now spends 14 per cent of national output on pensions, the third-highest in the OECD where the average spend is 9 per cent of GDP.

“France is prioritising spending to support older people rather than investing in its future,” said economist Maxime Sbaihi who wrote a book on the country’s looming demographic crisis. “We are denying our own demography.”

The proposal to delay the annual indexation of pensions is the “most minimalist” thing the government could have done, Sbaihi said, and it will not do anything to solve the pensions problem in the long term.

Barnier’s proposal would translate to a roughly €150 loss for a person on a pension of €1,400 a month — the national average — and the loss for even people on higher pensions should not exceed €200 for the year, according to estimates from business magazine Capital.

After France repeatedly and widely overshot its deficit target for this year, Barnier has put forth a €60bn fiscal package for 2025 that he says will bring back the deficit from above 6 per cent of national output to 5 per cent. It includes tax hikes on the wealthy and big corporations, paired with spending cuts on everything from health to green subsidies, including the proposal to delay the indexation of pensions.

Faced with loud opposition to the move, the Barnier government has since said it is open to insulating people on the smallest pensions. Amendments to that end could be proposed in parliamentary debate in the coming weeks.

Beyond the debate over pensions indexation, some experts argue that the overall system is plagued by an inherent unfairness between the generations — baby boomers have paid less into the system than they will receive in benefits, while the opposite will hold true for young people.

Today’s retirees enjoy pensions that correspond to a higher percentage of their former salaries than those of future generations given that people have to work longer, said Hervé Boulhol, a senior economist with the OECD. “If you look at what people pay in and what they will get in future pensions, there is no doubt that current retirees will be better off than future ones.

“In the context of a national crisis over the debt, it’s legitimate to ask the question about the efforts carried by each generation,” he added.

People above 65 in France have disposable income on par with those of workers, a rarity among OECD countries where, on average, older people have 88 per cent of the disposable income as workers do. The poverty rate is higher among 18-to-24 year olds than among those above 65.

After Macron spent significant political capital on raising the retirement age, his government turned around and put through a 5.3 per cent increase to pensions for 2024 at a cost of €14bn.

The boost meant that retirees’ pensions rose faster than workers’ wages this year, giving them more leeway to withstand inflation. The move also largely erased the savings that the increase in the retirement age was meant to generate, said Allianz chief economist Ludovic Subran, calling it “one of the worst political decisions on public spending in recent decades.”

When the then budget minister Thomas Cazenave dared to suggest in February that the government should reconsider the indexation of pensions to save money, he was immediately rebuked by Macron. “It was solely for electoral reasons since our party relies on older voters” and the European elections were coming up in June, said a person present at the cabinet meeting.

In addition to indexation of their pensions, retirees benefit from favourable tax policies that boost their disposable income, which is taxed at lower rates. Pensioners also benefit from an automatic 10 per cent deduction to compensate for work-related expenses, although they no longer work.

Getting rid of that loophole altogether would bring in €4.6bn a year to government coffers, according to the CPO, a government tax fairness watchdog. This tax deduction is “too general and badly targeted” and should be scaled back “given the continuous improvement of living standards [among retirees] compared to younger populations,” wrote the CPO.

But apart from economists who warn of the impact on future generations, there is surprisingly little tension between retirees and young people on pensions. Recent polls show three-fourths of respondents oppose Barnier’s proposal and the trend holds across all age groups, even the youngest.

Marc Guillaume, a 34-year-old engineer in Paris, said the French had a culture of solidarity between generations so many young people like him do not scapegoat retirees. He does not expect to get much of a pension at the end of his career.

“The system will be bust by then, but that doesn’t mean that people like my grandparents who worked hard all their lives should be cheated either.”