This article is an on-site version of our Chris Giles on Central Banks newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every Tuesday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Whether you are an economist trying to explain the consequences of a Donald Trump election victory or a central banker dealing with them, I have bad news for you. Calibrating Trump’s economic policies is extremely difficult. Explaining them is harder still.

This US election reminds me of the Brexit referendum. Back in 2016 in the UK, economists overwhelmingly backed the UK remaining in the EU: their models showed this was the better economic path and the in/out referendum was a relatively straightforward question.

Just to make everyone nervous (in a good or bad way, you choose) on US election day, the UK results were clear. Economists, polled by Ipsos MORI, thought Brexit sucked. Some 72 per cent thought it would have a negative effect on the UK economy. That was true. But they failed to convince the public and, shortly before the 2016 referendum, a plurality of those surveyed said Brexit would benefit the UK economy in the long term.

Compared with Brexit, calibrating Trump is even harder.

Is Trump serious?

Trump’s most important economic proposals are a substantial increase in US tariffs on imports, more tax cuts, having a say in monetary policy, the largest mass deportation of undocumented immigrants in history and greater use of fossil fuels.

The chart below is now a standard rendition of his main tariff proposal of 10 per cent universal tariffs on all imports plus a 60 per cent rate on goods from China. It would be a reversion to Smoot-Hawley effective tariff levels of the 1930s.

But is Trump serious? I don’t know. And nor do his acolytes.

In the FT alone, if you read interviews with Arthur Laffer, of Laffer curve fame and a former Trump adviser, or Kevin Hassett, Trump’s former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, they say the tariff talk is all a negotiating tactic. Robert Lighthizer, Trump’s former trade representative, disagrees. He wrote last week that tariffs work and US trading partners “shouldn’t blame us for shifting policy”.

If these people cannot agree, economists cannot model the likely policy — they do not know what it is.

Can he do it?

One of the big guessing games among economists is whether there will be a Republican or Democrat sweep of the presidency and both houses of Congress. This matters because the likely implemented policy will depend on whether Trump wins just the presidency or the presidency and Congress. This adds greater uncertainty to any economic modelling of a Trump victory.

Of course, it might also not matter if US political checks and balances are irrelevant in a Trump presidency that destroys the normal rules of government. Again, smart and informed people disagree. Alan Wolff at the Peterson Institute reckons Trump could not impose most of his trade policies in the face of opposition from Congress. The Cato Institute and the FT’s Alan Beattie are far from reassured.

I have no expertise here, except for stating the obvious: calibrating the consequences before we know the results is really hard.

Can economics model Trump?

It tries because that is what economists are paid to do.

But let us be honest. Economists do this badly.

I am going to pick on the IMF here, not because it is unusual but because it is very open about what it did and should be close to the best in the business. The IMF used an economic modelling approach to test Trump’s policies, with the results in the charts below. Click on the chart to toggle between Trump’s tariff policies alone, these plus global trade uncertainty (quite a nebulous variable), and these plus lower migration.

The results are puny.

For the global economy, they suggest that the world economy would grow 16.88 per cent by 2029 without Trump’s policies and 16.3 per cent with them. They show that high quality economic models do not remotely cope with regime breaks or structural shifts on which they will not have been estimated.

Using these results either to say Trump would be a disaster, as the IMF did, or that it doesn’t matter, are both seriously flawed.

Better is to take the approach of the FT’s Martin Wolf using the sweep of history to say that the prospect of a Trump presidency is “truly a fateful hour” for the world.

Are financial markets any better?

No.

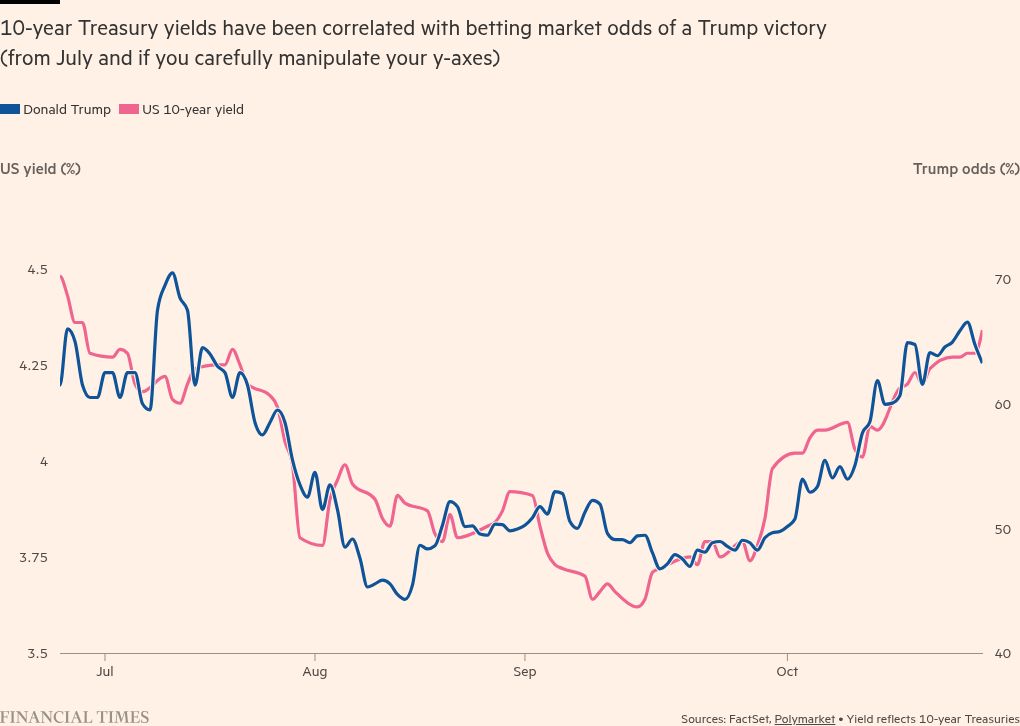

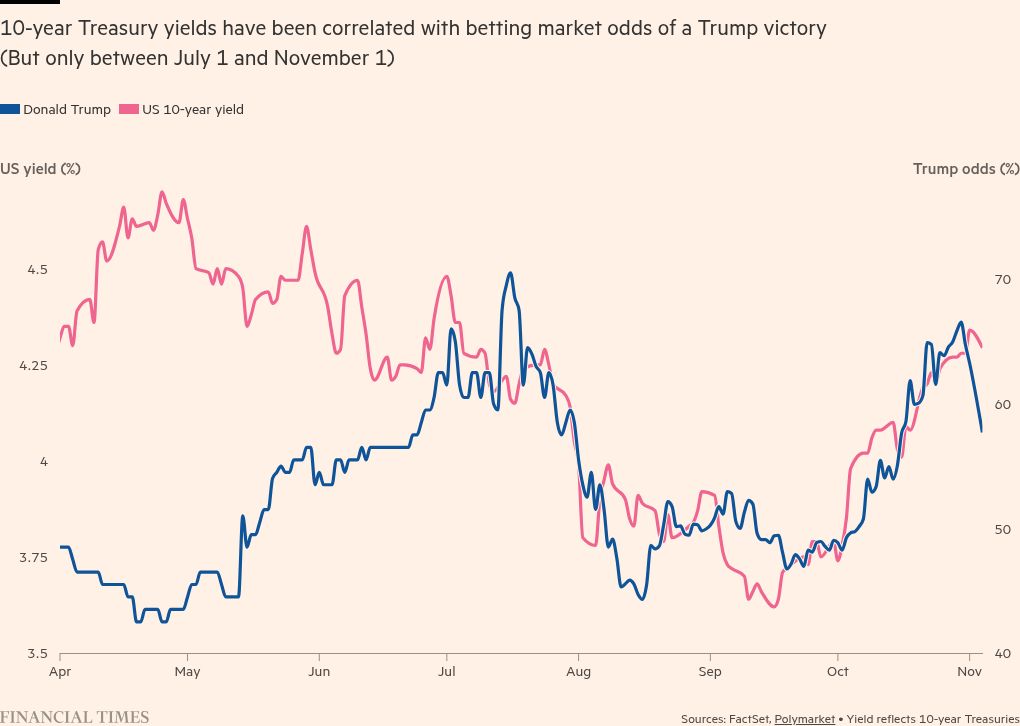

In recent days, the chart below has been depicted as showing the financial market calibration of a Trump victory with a correlation between his odds on the Polymarket betting website and 10-year US government borrowing costs.

Superficially, it appeared to be a neat way of gaining a financial market calibration of Trump’s economic policies.

The trouble is it didn’t work before July this year and didn’t work after November 1 when the betting odds narrowed sharply over the weekend, before rising again today. And remember in 2016 when Trump won, respectable market pundits expected a crash, which did not happen.

If the question is whether economics can calibrate a Trump victory, the answer is “not really”. Economics can tell you that his policies are damaging and a broad view can say the magnitude could be large.

Let’s hope we do not have to do a long retrospective on this.

The Budget and the Bank of England

The aftermath of last week’s UK Budget has been nervy in financial markets, which were surprised by the level of additional borrowing planned by the UK government alongside tax increases.

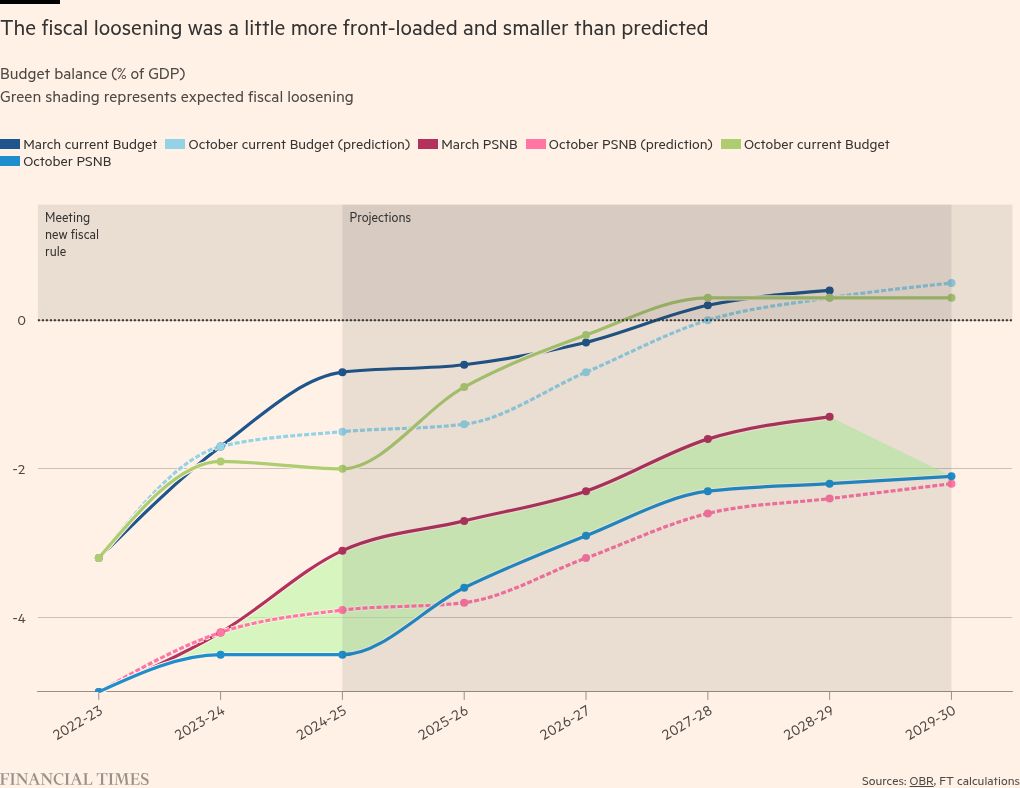

Readers of this newsletter would not have been shocked, since I sketched my expectations last week and they were broadly accurate. As the chart shows I underestimated the first year fiscal loosening, but also underestimated the planned tightening thereafter.

This is really quite a constrained fiscal policy and much of this year’s loosening has happened and will not concern the Bank of England.

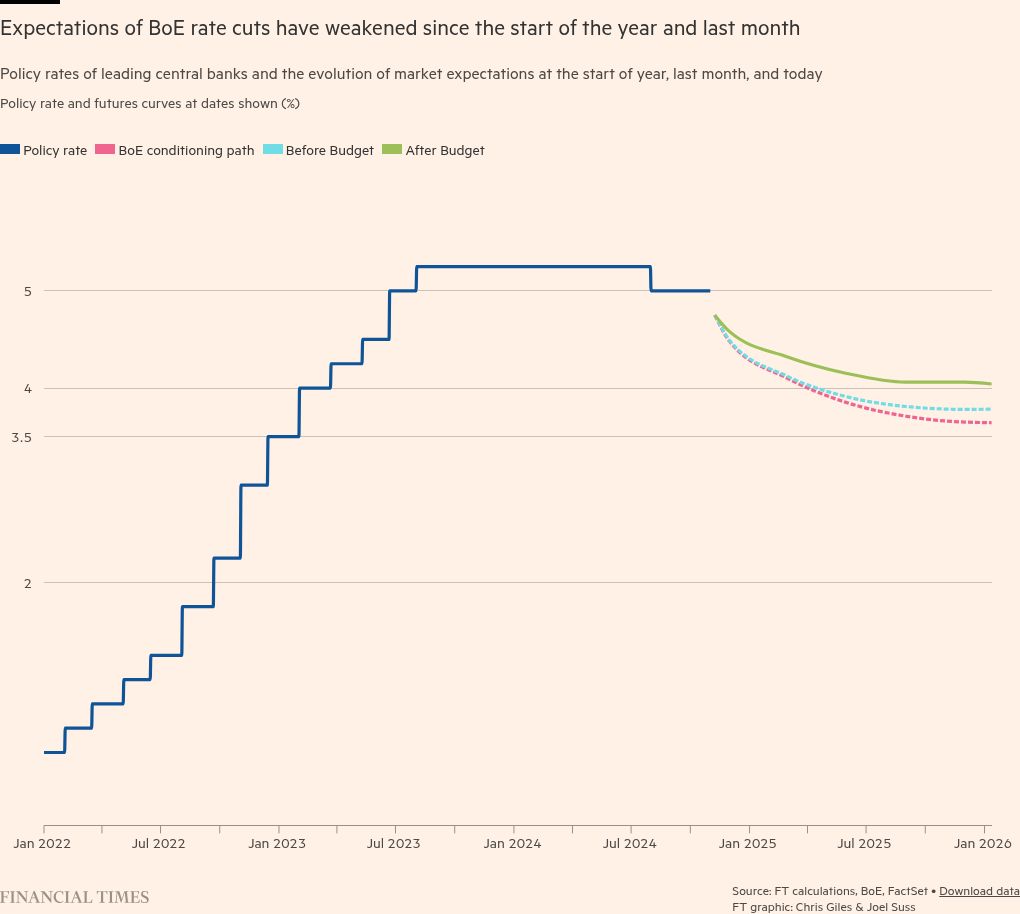

When the BoE comes to its latest interest rate decision on Thursday, likely to be a 0.25 percentage point reduction, its main difficulty will be explaining its new forecasts.

It will have conditioned these on forward market interest rates up to late October and these market rates are now roughly 0.4 percentage points higher. The BoE forecasts were based on interest rates falling from 5 per cent today to 3.65 per cent by the end of 2025. On Monday, financial markets expected rates to drop only to 4.05 per cent.

If the BoE forecasts inflation falling roughly to target over its two- to three-year forecasting horizon, as it probably will, that means the market expects fewer rate cuts than officials. It is perfectly reasonable for the market to take this position but explaining it will not be easy for the BoE.

To put it mildly, it is odd to condition a forecast on a rate path that is no longer remotely the market path.

What I’ve been reading and watching

A chart that matters

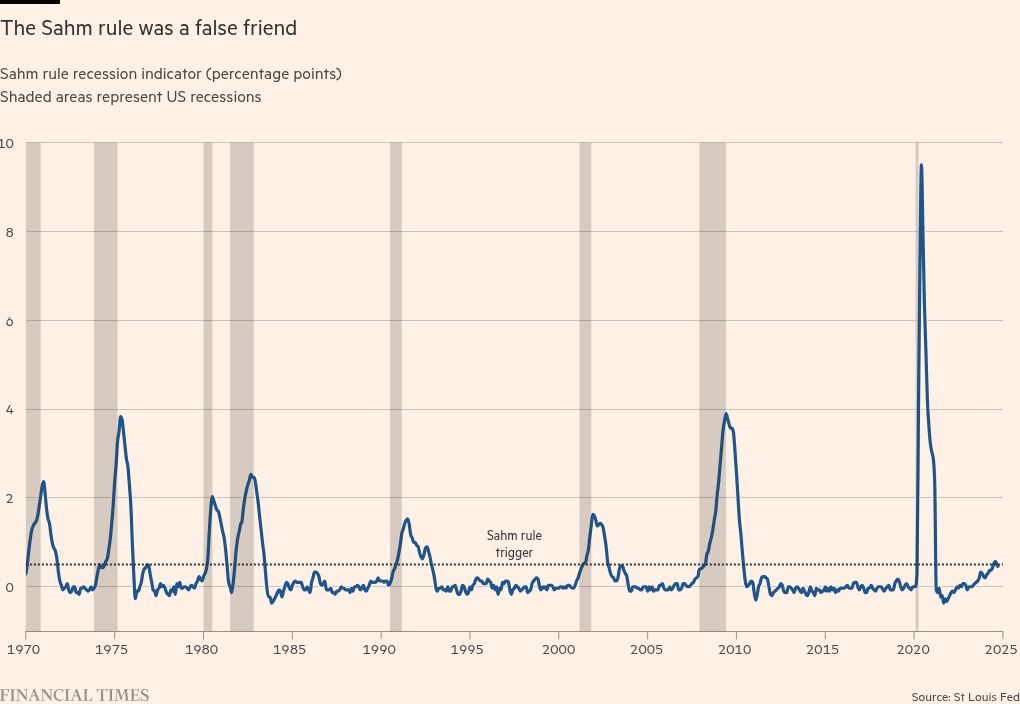

On Friday, a distorted US jobs report showed only 12,000 jobs were created in October. More encouraging was the unemployment rate, which stayed low at 4.1 per cent.

This means that the Sahm rule, the famous indicator of recession, now stands at 0.4 percentage points. The rule states that when three-month moving average unemployment has risen 0.5 percentage points from its low of the previous year, the economy is already in a recession.

To her credit, Claudia Sahm has been warning everyone who would listen that the rule might not work this time because the recovery from Covid was different. It serves as a warning not to trust rules of thumb without also engaging your brain.

Recommended newsletters for you

Free lunch — Your guide to the global economic policy debate. Sign up here

Trade Secrets — A must-read on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Sign up here