Karam Al-Kurd was an unlikely candidate to win the Palestinian Mathematical Olympiad.

The 17-year-old’s home in Deir al-Balah, central Gaza, has been shared over the past year with multiple evacuated relatives. The family often has little to eat beyond canned food. There is barely enough solar power to charge a phone, which Al-Kurd uses when he can to pursue his studies.

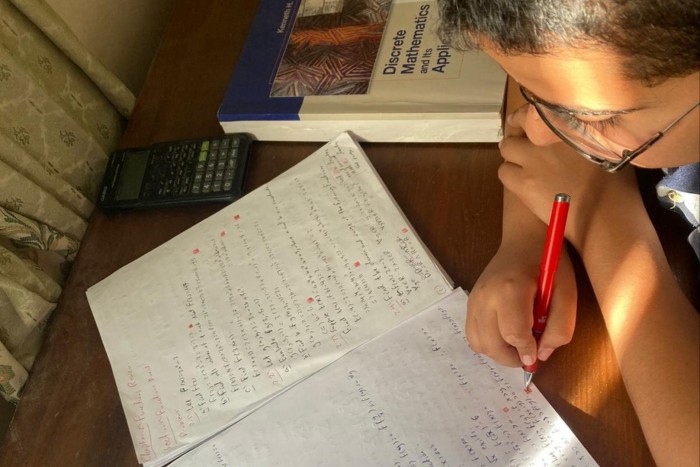

He could not attend training courses for the contest; with his school shut by Israel’s assault, he taught himself to solve advanced maths problems with help from his older brother and a handful of textbooks.

Those efforts paid off when his first-place score in the five-hour online test won him a spot at the international final in UK this July, alongside teams from 108 other countries.

It would have been his first time leaving Gaza.

“He was an undiscovered talent,” said Samed AlHajajla, the 25-year-old leader of the Palestinian International Mathematical Olympiad team.

Competitive mathematics may sound esoteric, particularly in a war-torn territory where many young men dropped out of school even before the conflict shut down educational institutions.

Now, academic youngsters must balance their attempts to keep studying with evading heavy munitions, finding clean water to drink and navigating checkpoints.

Since Hamas’s attack on Israel last year triggered the war, Israel’s offensive in Gaza has killed more than 43,000 people, according to local health authorities, and left much of the strip in ruins, its population almost all displaced.

But AlHajajla, who was a driving force behind Palestine competing in the Olympiad for the first time in 2022, is determined not to let the war keep young Palestinians from top-level academic success.

“You can know all the theories and the laws. It’s not about that. It’s about creative, critical thinking — thinking outside of the box,” he said.

“Getting people to think properly, think in the abstract, that’s the essence of problem-solving. You can then build solutions and models that can be applied to anything.”

Over its 65-year history the IMO has been a stepping stone for some of the world’s keenest young mathematical minds, including about half of all Fields medallists.

The six questions in the annual final challenge students well beyond school level. Solving just one problem earns an honourable mention, which opens doors to top universities.

AlHajajla returned from London, where he worked as a software engineer for Meta, to the West Bank last year to train students for the IMO and its computer science equivalent through his social enterprise Meshka. Almost 1,000 young people aged 14 to 18 applied to the free programme this year.

The four selected for the 2024 team, including Al-Kurd, were put through an intensive course over Zoom calls with Palestinian and international mathematicians.

Hasan Saleh, 17, could only join a few sessions on the phone he shares with six family members. He fled his home in Gaza City a week into the war.

“I left behind every tool — my laptop, calculator, math notes, and even some of the problems I invented,” he said. It was a month until he could get online again.

He qualified for the final despite being forced to flee four times in the past year, once with “bombs literally flying above us”.

But the closure of the Rafah crossing to Egypt in May meant he and Al-Kurd did not even apply for UK visas, as they knew there was no chance they could leave Gaza.

The remaining two team members, who live in the West Bank, planned to travel to the UK, but their passports and approved visas disappeared in transit somewhere between the British consulate in Jerusalem, the embassy in Tel Aviv and printers in Abu Dhabi.

It is still unclear what happened; the IMO’s ethics committee is investigating.

It was a hard blow for the team, which had hoped to win its first medal.

AlHajajla believes the IMO should have made alternative arrangements, such as allowing students to compete online. “If it was Ukraine, I think they would have allowed it,” he said.

Gregor Dolinar, president of the IMO, said he and the board “were hoping until the last moment they would be able to come”. He said they would work to ensure that teams affected by conflict can compete next year in Australia, including through online access or financial aid.

Saleh now lives in a tent in an area that Israel has designated as a “humanitarian zone”, which has still been hit by multiple air strikes. He would like to enter the Olympiad again, but it has been difficult to study. It took him months to register for online school.

“It’s been one year since I [had] any formal education,” he said.

Al-Kurd is trying to complete his final two years of school online. He spends much of his free time studying topics such as calculus, number theory and logic, taking a university-level course on his smartphone.

The son of a lawyer and a homemaker, Al-Kurd is rare among Gazans in having been able to stay in his home. But like most people in the territory, has lost members of his extended family to the war, a toll he is reluctant to discuss.

He could not take up a scholarship offer from a school in India this autumn, but hopes to apply to university abroad next year — perhaps Stanford or MIT.

“Fear and uncertainty [about] the future makes it hard to focus sometimes,” he said. “Maths has helped me a lot because it separated me from the horrible situations and motivated me to stop thinking about war and focus on what I love to do.”

He added: “When you study mathematics, you stay excited to learn more to see the big picture.”

For AlHajajla, the big picture is inspiring a generation. He wants to establish training programmes in every Palestinian city.

“It’s so important to improve problem-solving skills for Palestinian kids, because they are the future and they are missing so much,” he said.

“Our education system is not really good. Now we have examples of [past] students who are interning in Facebook and Google or got scholarships at the best universities in the world.

“If we can scale that to a whole country, Palestine will be a different place.”

Could you solve an IMO problem?

Problem 5 (2024) Turbo the snail plays a game on a board with 2024 rows and 2023 columns. There are hidden monsters in 2022 of the cells. Initially, Turbo does not know where any of the monsters are, but he knows that there is exactly one monster in each row except the first row and the last row, and that each column contains at most one monster.

Turbo makes a series of attempts to go from the first row to the last row. On each attempt, he chooses to start on any cell in the first row, then repeatedly moves to an adjacent cell sharing a common side. (He is allowed to return to a previously visited cell.) If he reaches a cell with a monster, his attempt ends and he is transported back to the first row to start a new attempt. The monsters do not move, and Turbo remembers whether or not each cell he has visited contains a monster. If he reaches any cell in the last row, his attempt ends and the game is over.

Determine the minimum value of n for which Turbo has a strategy that guarantees reaching the last row on the nth attempt or earlier, regardless of the locations of the monsters.

IMO 2024 problems

IMO 2024 solutions