Our planet is changing. So is our journalism. Keep up with the latest news on our Climate and Environment page.

Sign up here to get this newsletter in your inbox every Thursday.

This week:

- How one city learned to love congestion pricing

- The Big Picture: High-speed rail for Canada

- Should gas-powered leaf blowers be banned?

How one city learned to love congestion pricing

Imagine, if you will, that your city is proposing a fee for cars to enter the downtown core, with prices being the steepest during rush hour — the idea being that it will help put a stop to bumper-to-bumper traffic and make your city move better. Would residents be all for it?

Unlikely.

But what if it worked? Do you think people would change their minds?

Well, that’s exactly what happened in Stockholm in the early 2000s.

City council decided to conduct a trial run, putting in place a congestion charge, and then have people vote on whether or not they wanted to keep it in place.

“At the time, this was seen as, you know, like a suicide idea. Who would ever do this?” said Jonas Eliasson, director of transport accessibility at the Swedish Transport Administration, who led a team that did the modelling and evaluation of the pricing ahead of the trial, which was introduced in January 2006.

“We had something like maybe 60, 70 per cent of public opinion against congestion pricing for all the usual reasons: it will never work, it’s unfair, car drivers have to drive,” he said. “But then it was introduced, and even to my surprise, I must say, it worked even better than we thought.”

The city did some planning ahead of time, purchasing more than 100 buses, adding 16 new bus routes, and building park-and-ride facilities, covering a roughly 35 square kilometre area.

It was a wild success. Traffic in the area dropped far more than Eliasson and his team had predicted — 20 per cent.

Eliasson said that, comparatively, a holiday that falls on a weekday reduces traffic by roughly 10 per cent.

Buses moved so well that schedules were changed so that drivers weren’t left waiting at the end of the route for long periods of time until their next run. Large logistics companies altered their delivery scheme because they could deliver more parcels than they could before.

Conversely, revenues were 10 per cent lower than estimated because the congestion pricing simply worked so well at discouraging drivers to enter the city core. But that was okay: it wasn’t put in place to generate revenue.

Later analysis found that high-income individuals, who drove more, were affected more than low-income individuals, and that young and low-income people benefitted from lower transit fares.

After the trial run, congestion pricing was paused in the lead-up to the referendum. What happened? Traffic congestion went back to the way it had been.

The effects were clear, tangible and residents liked it; the city improved.

The referendum passed by a large margin.

Since then, public transport has increased while car traffic is a bit lower than in 2006, Eliasson said.

The congestion pricing was put in place permanently in 2007. It has lowered carbon emissions by roughly two to three per cent, Eliasson said. It’s also helped reduce pollution in the inner city by 10 to 15 per cent.

Other studies in cities like London and Milan have found similar reductions.

Could this work in a city like Toronto, which last year was ranked by a navigation software company as the worst traffic in North America and the third-worst in the world?

“Congestion charging works … especially if we can use the funding and the money that’s generated to pay for alternatives,” said Matti Siemiatycki, professor of geography and planning and the director of the Infrastructure Institute at the University of Toronto.

But it needs to be done in tandem with things like an increase in public transportation, he said. For example, the Greater Toronto Area is adding the Eglinton Crosstown light rail transit line, Metrolinx’s Ontario Line and expanding GO Transit services.

“We’re in the midst of the biggest transit investment in a generation,” he said.

Meanwhile, Eliasson said that in Stockholm, congestion pricing isn’t even a controversial subject anymore; it’s more akin to talking about speed limits or traffic signals.

“You don’t think so much about it,” he said.

— Nicole Mortillaro

Old issues of What on Earth? are here. The CBC News climate page is here.

Check out our podcast and radio show. In our newest episode: When some climate-conscious Swifties learned that Canada’s biggest fossil fuel financier, RBC, is an official partner for Taylor Swift’s Eras tour in Vancouver and Toronto, they jumped into action. But can uniting Swifties online translate to change? Or is it a trend that will fizzle over time? Meanwhile, What On Earth youth columnist Aishwarya Puttur breaks down why social media campaigns are on the rise for Gen Zs.

What On Earth31:10The contest trying to turn Swifties into climate crusaders

What On Earth drops new podcast episodes every Wednesday and Saturday. You can find them on your favourite podcast app, or on demand at CBC Listen. The radio show airs Sundays at 11 a.m., 11:30 a.m. in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Reader feedback

What to do with your pumpkin after Halloween? Mine is one of many Toronto neighbourhoods that have a “pumpkin parade” in the local park — neighbours line up and light their carved jack-o’-lanterns by the hundreds. It’s a showcase of creativity and a magical sight. The city provides bins to ensure they will all get composted at the end of the night. Here’s a photo from a past event:

We’d like to hear about local initiatives that make YOUR community a little greener. Write us at [email protected]. (And feel free to send photos too!)

Write us at [email protected].

Have a compelling personal story about climate change you want to share with CBC News? Pitch a First Person column here.

The Big Picture: High-speed rail in Canada

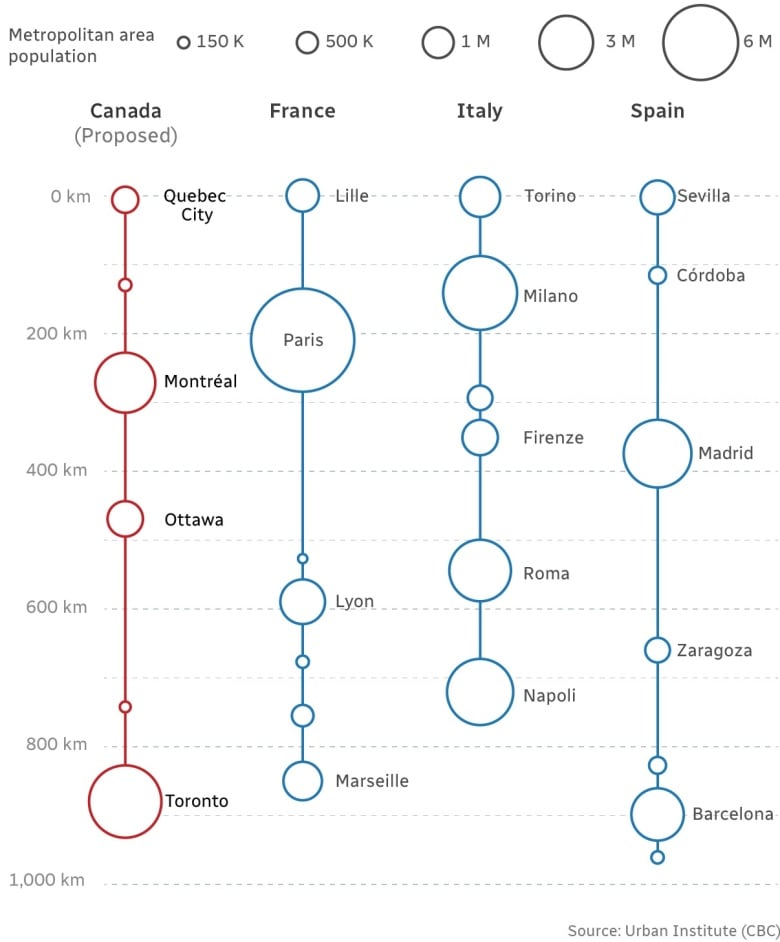

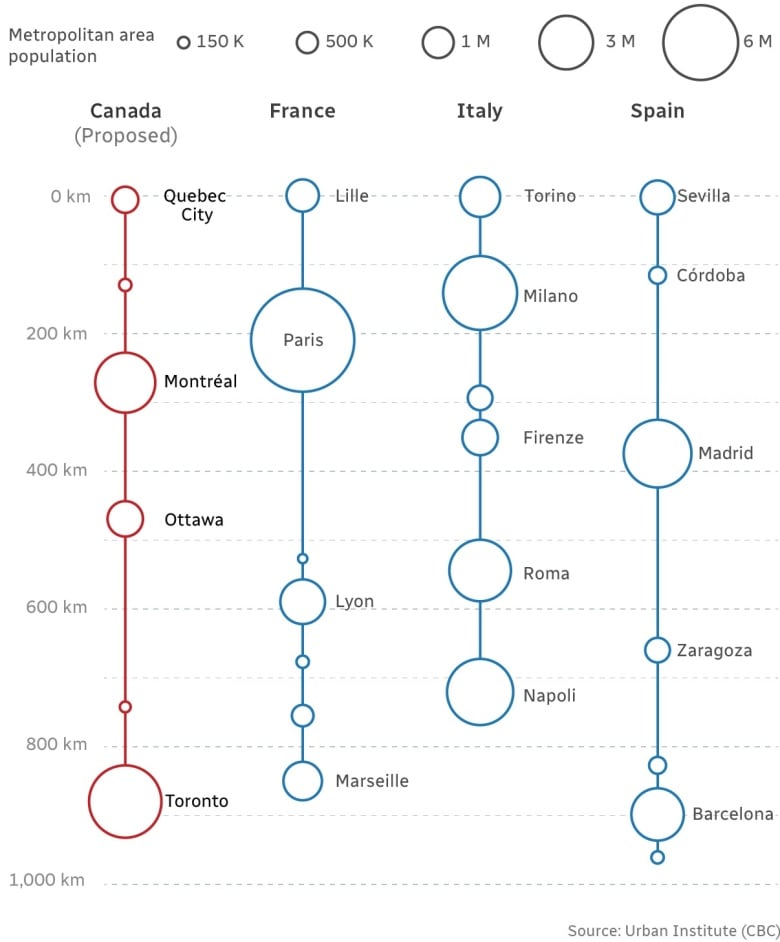

The federal government is expected to move ahead with plans for a high-speed rail line that would link Montreal and Toronto, as CBC reported this week. While skeptics sometimes argue Canada is too spread out for high-speed rail, the graphic below shows how the area served by the line is similar in terms of both population density and distance to those already in operation in France, Italy and Spain. For more on the proposed rail line, check out this story.

— Benjamin Shingler

Hot and bothered: Provocative ideas from around the web

Should gas-powered leaf-blowers be banned?

Mark Nevitt describes the views on his walk or bike to work in Atlanta as “stunningly beautiful” thanks to the city’s lush tree canopy.

But when autumn arrives, not only do the trees shed their leaves, there’s another seasonal change the Emory University environmental law professor says he’d rather do without.

“My beautiful bike ride to Emory’s campus was really punctuated and made really unpleasant by gas-powered leaf blowers,” Nevitt said in an interview with What on Earth. “That’s what led me down this rabbit hole of looking into their climate harms.”

The common gas-powered leaf blower has a two-stroke engine, says Nevitt. That means it cranks out more air pollution than a high-performance pickup truck, according to 2011 data from Edmunds.

Nevitt said he was outraged when a bill was passed in the Georgia senate last year that seeks to prohibit the state’s cities and counties from banning gas-powered leaf blowers.

“We’re seeing a powerful lobby of landscape companies that are actually pushing back against this,” said Nevitt. “[They] make quite a lot of claims about the transition costs … as you move from gas to electric.”

In Canada, there’s a similar discussion about banning two-stroke gas-powered blowers. In Vancouver, the West End became the first neighbourhood in Canada to ban them in 2004. Last October, Westmount in Montreal also banned the blowers. And Toronto City Council made the decision to transition to zero-emissions outdoor power equipment in July 2023, and will conduct an online survey next month to gather feedback from residents and businesses about how the transition will unfold.

In cities like Calgary, however, the ban is still in the proposal stage. A community group called Project Calgary launched a petition that had more than 2,800 signatures toward its goal of 3,000 at the time this article was published.

Nevitt says that almost all other uses of two-stroke gas engines, including in automobiles, have been phased out.

Joe Vipond, an emergency medicine physician in Calgary and past-president of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, says leaf blowers pose concerns for both the environment and health.

“The things that come out of the exhaust of a leaf blower is a combination of the combustion products, like the carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and that particulate matter 2.5, which is the real bad pollutant that people know about.”

“If you use it for one hour, the amount of smog-forming air pollution is similar to driving a sedan for 1,750 kilometres,” he said, citing data from the California Air Resources Board.

Both Vipond and Nevitt also say that regulation of these devices is an equity and social justice issue.

“The people most exposed to the pollutants and to the noise from these machines are the people that work with them every day,” said Vipond. “And these are generally low-income people who are the least able to avoid these risks.”

The sound produced by leaf blowers that run on gas causes immense harm, says Nevitt. “Just being exposed to [it] can [cause] permanent hearing loss.”

When it comes to climate work, people often resist change unless a viable alternative is available, says Vipond. However, with the availability of effective electric leaf blowers — both plug-in and battery-powered, “there’s really no reason to have gas-powered leaf blowers.”

Sheldon Ridout is the owner of The Silent Gardener, a B.C.- based all-electric landscaping company. When it first started 24 years ago, the company used only unpowered equipment, such as rakes and brooms.

“Unfortunately … on larger sites, that gets to be a lot more difficult,” said Ridout.

Around 10 years ago, Ridout began using lithium-battery equipment, and all of the company’s tools are now powered by lithium batteries.

“All those little myths about, ‘Oh, I’d have to have so many batteries and they only last for 15 minutes, and they’re not powerful’ … are all 10-year-ago problems,” said Ridout.

But Ridout is opposed to municipalities banning gas-powered blowers.

“If you’re pounding on someone to do something, you’re going to get a lot more resentment,” said Ridout.

Instead, Ridout says that to bring about change, residents need to advocate for it as consumers.

“That’s your quickest change.”

— Catherine Zhu

Stay in touch!

Thanks for reading. Are there issues you’d like us to cover? Questions you want answered? Do you just want to share a kind word? We’d love to hear from you. Email us at [email protected].

Sign up here to get What on Earth? in your inbox every Thursday.

Editors: Emily Chung and Hannah Hoag | Logo design: Sködt McNalty