Gustave Caillebotte was so modest that when bequeathing paintings by his Impressionist friends to France — the foundation of the Musée d’Orsay’s great collection — he omitted his own. His most adventurous pictures, too startlingly modern to appeal to conservative French taste, subsequently found homes abroad. Now they are back for the Orsay’s vast, rare retrospective Caillebotte: Painting Men. A riveting finale to this year’s many exhibitions celebrating Impressionism’s 150th birthday, the show adds nuance and flavour to our understanding of the artist and the movement.

Centre stage is the huge masterpiece of urban alienation “Paris Street, Rainy Day”, loaned from Chicago. Life-size figures in uniform dark attire, anonymous under their umbrellas, cross glistening wet pavements between Baron Haussmann’s regimented apartment blocks. Luminous despite the grey weather as sun pierces the cloud, it is photographic in its clarity with sharp angles and cropped composition. Painted in a dry facture rather than impressionism’s softening blended strokes, “Paris Street” still surprises for its intense realism and sheer monumentality.

It starred at the 1877 Impressionist exhibition alongside Monet’s “Gare St Lazare” series, Renoir’s party “Dance at le Moulin de la Galette” and Caillebotte’s own steam and steel stunner “Le Pont de l’Europe”, the perspective manipulated so that the station bridge’s colossal metal trusses surge towards us. All three were unprecedented visions of the capital, recognisable but imaginatively transformed.

In “Le Pont”, a well-dressed man and woman, possibly a couple, walk several paces apart; he eyes a trainspotting worker (some argue a male prostitute) while a defiant dog enters the picture tail first. It’s a singular composition, harsher and more geometric than Monet’s stations, opposite in mood to Renoir’s warm sociability. Instead of Impressionist dash, Caillebotte offers a meticulously constructed world.

Oil sketches and drawings show how deliberately he planned such works. Sometimes he zooms in on details, as in Kimbell Art Museum’s “On the Pont de l’Europe”, a pattern of grey girders, black hats, a trio of overcoats. Sometimes he experiments with birds’ eye views, unknown in painting at the time, pushing almost to abstraction — the circular forms and empty spaces in “A Traffic Island, Boulevard Haussmann” and “Boulevard Seen from Above”. In each, a few top-hatted figures hurry past.

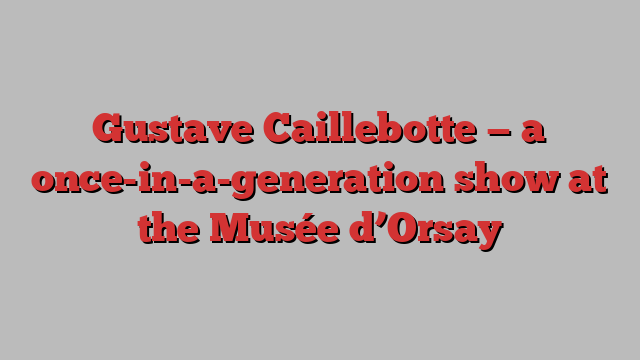

Lone men haunt Caillebotte’s paintings. From his expensive apartments, he depicted Paris from above, through the superior gaze of a single wealthy man like himself, leaning out across balconies whose scrolled ironwork lyrically counterpoints the arrow-straight boulevards below. “Man on a Balcony” is a recurring title for these elegant balancing acts: affluent men the masters of all they survey, yet in retreat from the public sphere to the privacy of the 19th-century bourgeois interior. On their balconies, they stand between the two.

The show argues that, on the one hand, Caillebotte depicts a gendered reality: the broad avenues and open squares with which Haussmann rebuilt 19th-century Paris were “a fundamentally male domain”, an arena for confident wealthy flâneurs. On the other, following defeat in the Franco-Prussian war, the beginnings of women’s emancipation and what the curators call “the emergence of homosexual subcultures”, men were perhaps not so cocksure. Thus Caillebotte’s “artistic vision was inextricably bound up with a questioning of masculine identity that seems freshly relevant today”.

The initial “Young Man at His Window” (1876) carries this ambivalence. Caillebotte’s brother René stands in nonchalant, virile pose: legs apart, hands in pockets, but restless and ill at ease. Months later he died, probably by suicide.

Caillebotte as proto-structuralist, fulfilling Baudelaire’s call for a “painter of modern life” by exploring not just the look of the new Paris but its social systems, intersection of people, buildings, infrastructure, is certainly persuasive.

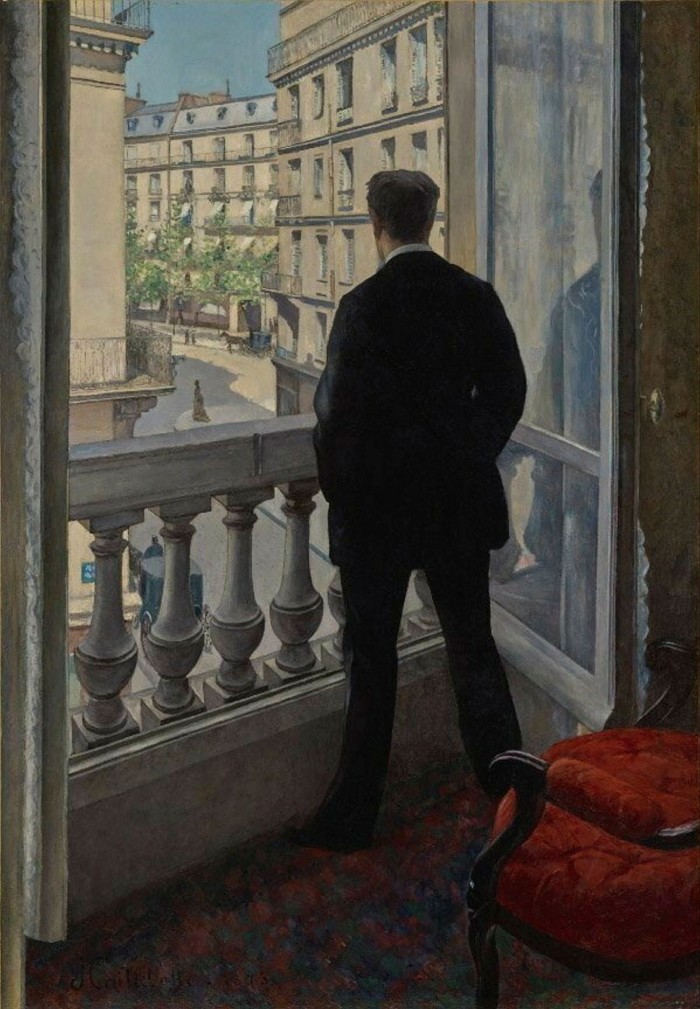

Unlike his peers, he portrayed diverse classes: smocked “House Painters” on ladders, his elderly butler “Jean Daurelle”. His career began with the bare-chested, sweaty labourers in “Floor Scrapers”, kneeling and stretching to build his studio. Bathed in cool light, beautifully finished and detailed, the curled wood shavings and rounded backs echoing the looping iron railings, this was intended for the academic Salon. Its rejection, as much for the frank depiction of working bodies as the expressively exaggerated, tilting floor, turned Caillebotte rebel overnight. He joined the Impressionist shows of 1876-82, largely funded them, and purchased paintings from his impoverished friends.

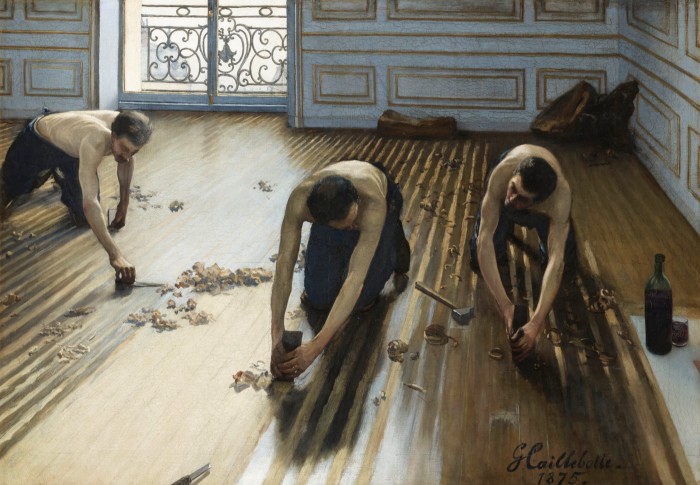

Instinctively collegial, he thrived in early Impressionism’s co-operative spirit, learning from Monet’s light effects and Degas’s spatial dynamics. Two outstanding large figure studies acknowledge the influences, though their oddness is Caillebotte’s own: “Boating Party”, an incongruously suited, vigorous blond rower close up against the picture plane, and the disconcertingly intimate “Man at his Bath”, drying himself next to a tin tub as we survey ruddy buttocks, muscular back, wet footprints.

There is also an animated representation of Caillebotte’s bachelor set, “The Bezique Game”, and numerous affectionate male portraits. “Young Man playing the piano” depicts his composer brother Martial, long fingers mirrored in the instrument’s reflective varnish.

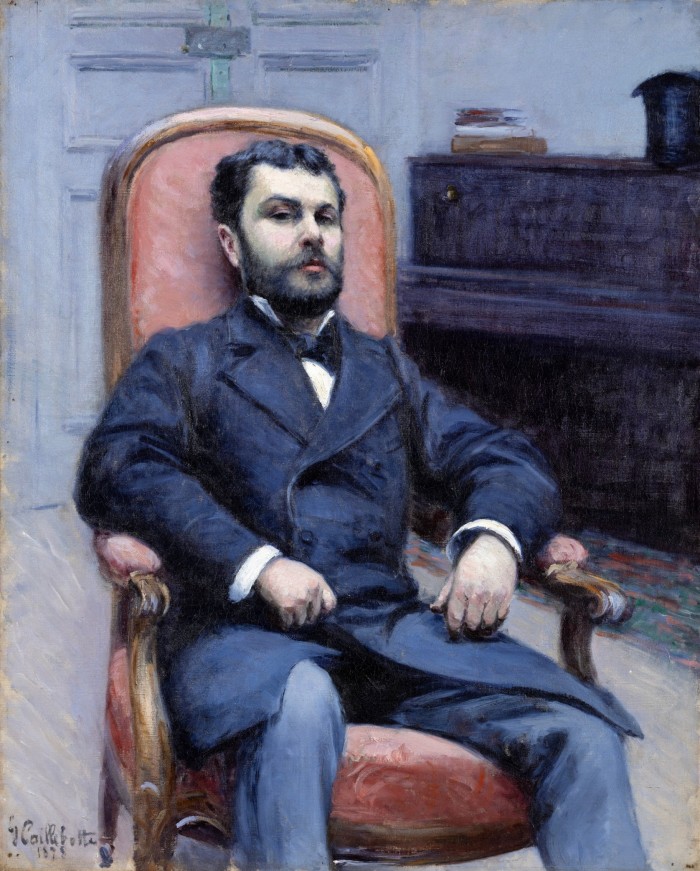

Gold-panelled interiors and plush seats feature in “Portrait of Mr G (Gallo)” and “Portrait of Mr J R (Jules Richemond)”. “He has friends whom he loves and is loved by; he sits them on strange sofas, in fantastical poses,” wrote a contemporary critic. “No doubt perceived as feminine and emasculating,” reads the Orsay caption, one of many hinting at homoerotic interests, for which no evidence exists — Caillebotte lived with a long-term female partner.

As the Impressionists drifted apart after 1882, Caillebotte painted less. He threw himself into his local yacht club, designing and racing boats, and into a contrasting solitude, creating a garden in Petit Gennevilliers, near Monet’s Giverny. Already in 1879 he chose as background for an awkward “Self-Portrait at the Easel” not his own work but Renoir’s “Le Moulin”, which he had just bought. He became known primarily as a collector.

It is unfortunate that to support the “painting men” theme, far too many mediocre boating pictures (“serious, men-only” sports) are shown, whereas the swan song of the two years before Caillebotte’s untimely death in 1894, the truly original flower paintings, are entirely absent. In these flattened still lifes of nasturtiums, dahlias, assiduously cultivated orchids, Caillebotte abandoned social realism for a fin-de-siècle hothouse interiority. They were a revelation in Caillebotte, Painter and Gardener, at Giverny’s Musée des Impressionnismes in 2016.

Dependent on foreign loans, Caillebotte exhibitions at this scale happen in Paris only once a generation — the previous ones were 1995 and 1951. The Musée d’Orsay’s is a significant, memorable show, but how disappointing that rather than simply securing the best works across all periods, the curators narrowed their approach by the fetish of gender studies. Social history takes you so far in explaining an artist, but as Caillebotte insisted, “a painter’s real argument is his paintings”.

To January 19, musee-orsay.fr, then Getty Museum, Los Angeles, February 25-May 25 and Art Institute of Chicago, June 29-October 5

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen