Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer repeatedly warned of brutal choices in the lead-up to Wednesday’s Budget. His chancellor unquestionably delivered.

Rachel Reeves served up the UK’s biggest tax-raising package since the early 1990s, hammering employers with a £25bn annual national insurance increase alongside higher capital gains tax and a crackdown on non-doms, to help fund a £70bn annual increase in public spending.

But forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility, UK’s fiscal watchdog, suggested it would take more than this single Budget to achieve her key aims — to durably repair the public finances and end the UK’s slow-growth malaise.

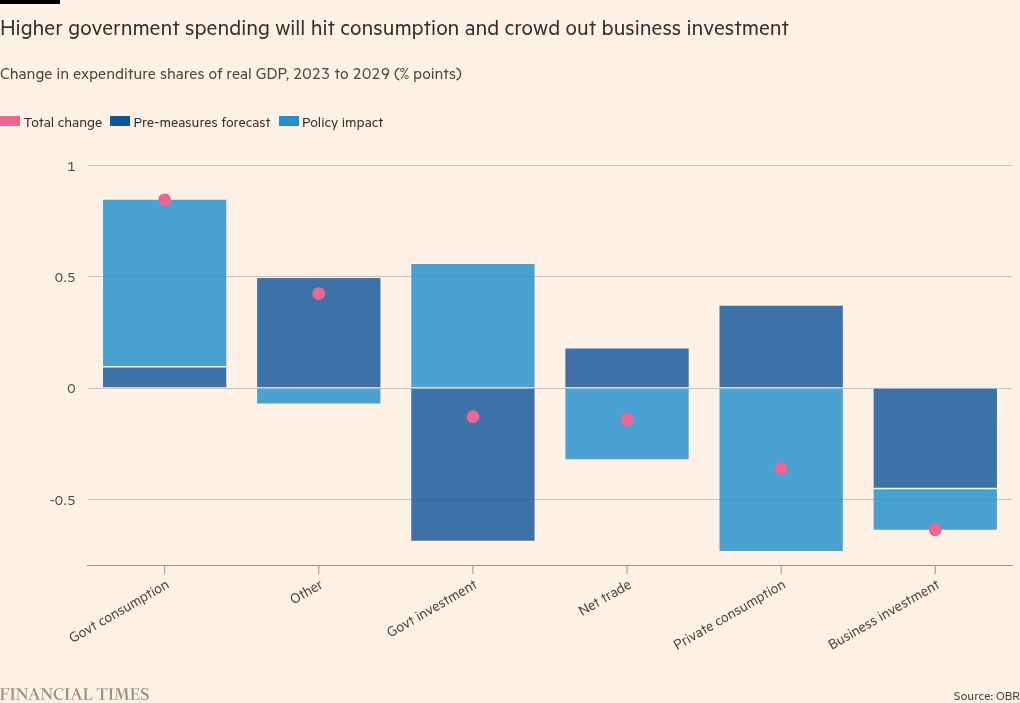

The OBR’s forecasts show steep increases in public spending will create an initial “sugar rush” of growth, but will make little difference to GDP over five years, with the state playing a bigger role in the economy at the expense of consumers and businesses.

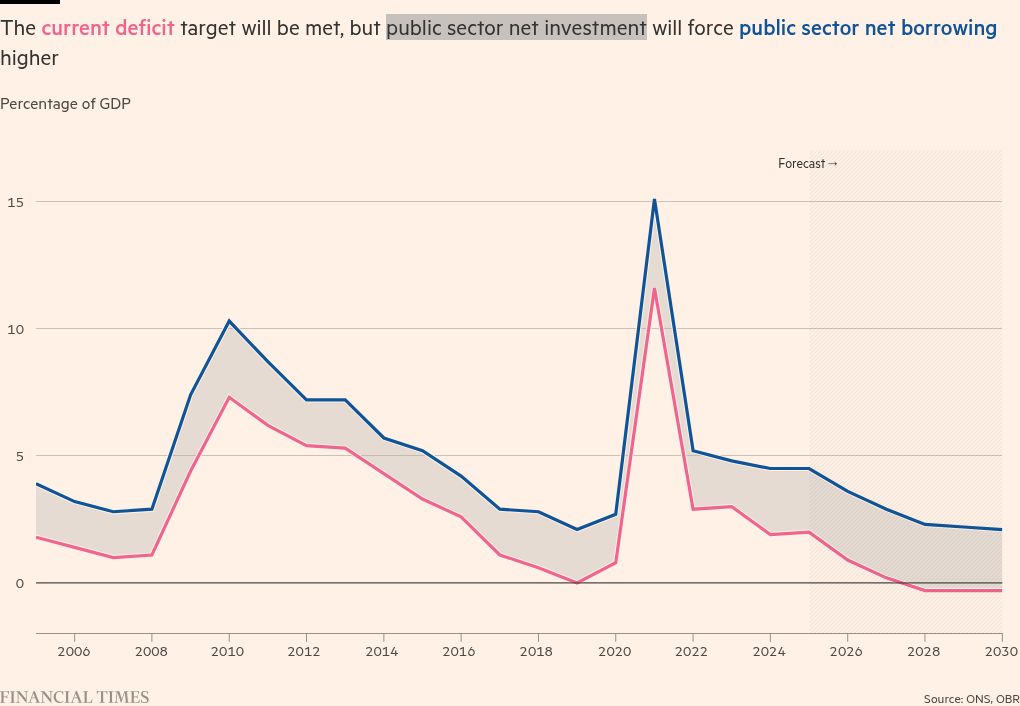

And although the chancellor will readily meet her newly drawn fiscal rules, she has relaxed fiscal policy compared with the position in March. Borrowing will be an average of £28bn over the next five years and the government will spend more than £100bn on debt interest in each of those years.

“That cost doesn’t just go away because you’re targeting a different measure,” said Richard Hughes, chair of the OBR, adding rising debt servicing costs were “one reason the tax burden is so much higher”.

Some extra borrowing was widely expected — Reeves has been clear that she is shifting her fiscal regime to enable tens of billions of pounds of extra investment.

But the verdict from the OBR is that the Budget amounts to one of the biggest fiscal loosenings of recent decades, with overall borrowing set to be £142bn higher than previously expected between 2024-25 and 2028-29.

The combination of new taxes and borrowing will permit Reeves to raise spending by about £70bn a year over the next five years, bringing the size of the state to 44 per cent of GDP.

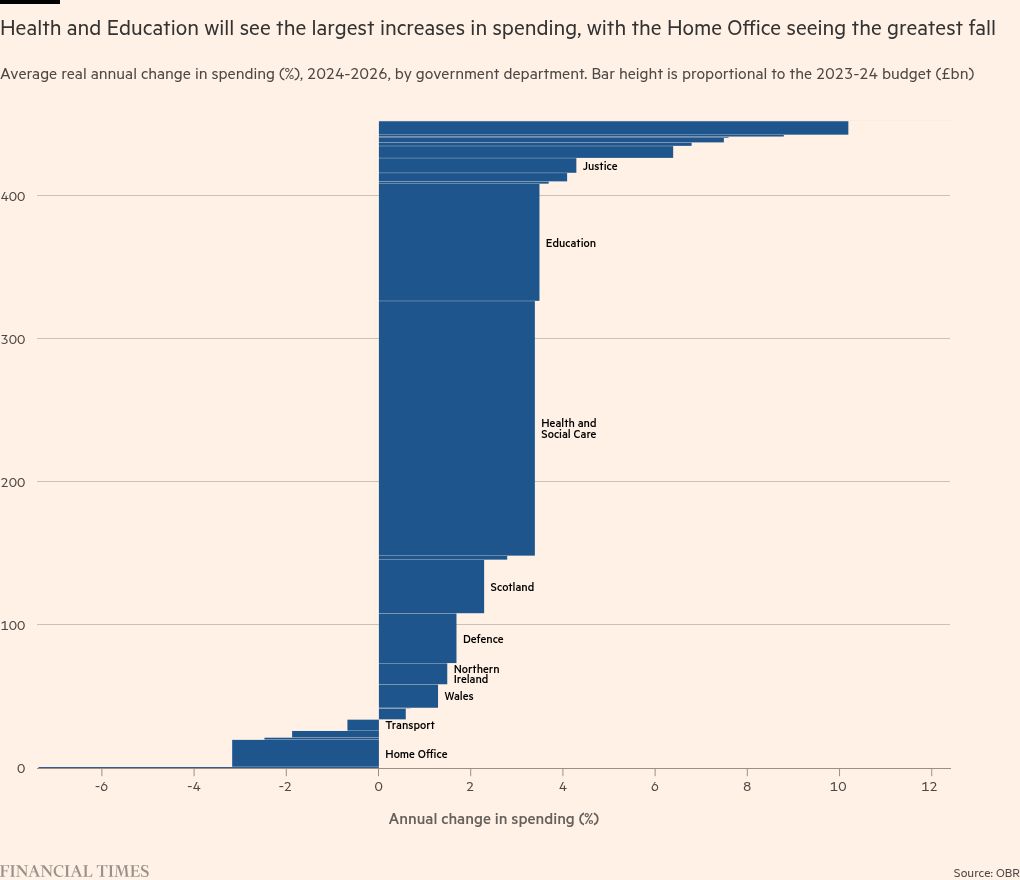

Roughly a third of this will go towards capital spending, with the remainder boosting day-to day spending on public services — of which the lion’s share will go to the NHS and schools.

Paul Johnson, head of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, warned that the spending increases are heavily “front-loaded”, with day-to-day spending rising by 3.1 per cent in 2025-26 before growth would decrease sharply to 1.3 per cent a year in real terms thereafter.

He was sceptical about the promised cuts in the future: “A government splashing the cash in the short term and promising to be more austere in future? Stop me if you think you’ve heard this one before.”

Pockets of austerity may linger in areas of public services, forcing the government into fresh rounds of tax rises. Hughes noted that outside protected areas such as health, defence and overseas aid, spending on all other departments would still be falling by 1.1 per cent a year in the final four years of the forecast.

Meanwhile, the renaissance in economic growth Reeves is hoping for will take a long time to materialise. The OBR said the net effect of all measures announced in the Budget would be positive only from 2032-33 onwards — Labour would need to win the next election to enjoy the effects.

The boost to capital spending would raise potential output by 1.4 per cent if it was sustained over 50 years.

In the short term, the fiscal loosening was likely to both fuel inflation and crowd out private sector investment, the OBR said, noting that it could lead the Bank of England to set a path for interest rates about 0.25 percentage points higher than it would otherwise have done.

David Miles, an OBR official, described this as “neither completely trivial nor a game-changer”. But consumers will face a triple whammy of higher prices, higher borrowing costs and lower wages relative to previous expectations — even as Reeves keeps tough welfare policies in place.

The OBR said CPI inflation would rise to 2.6 per cent next year, up from a previous projection of 1.5 per cent, before easing as the BoE took action.

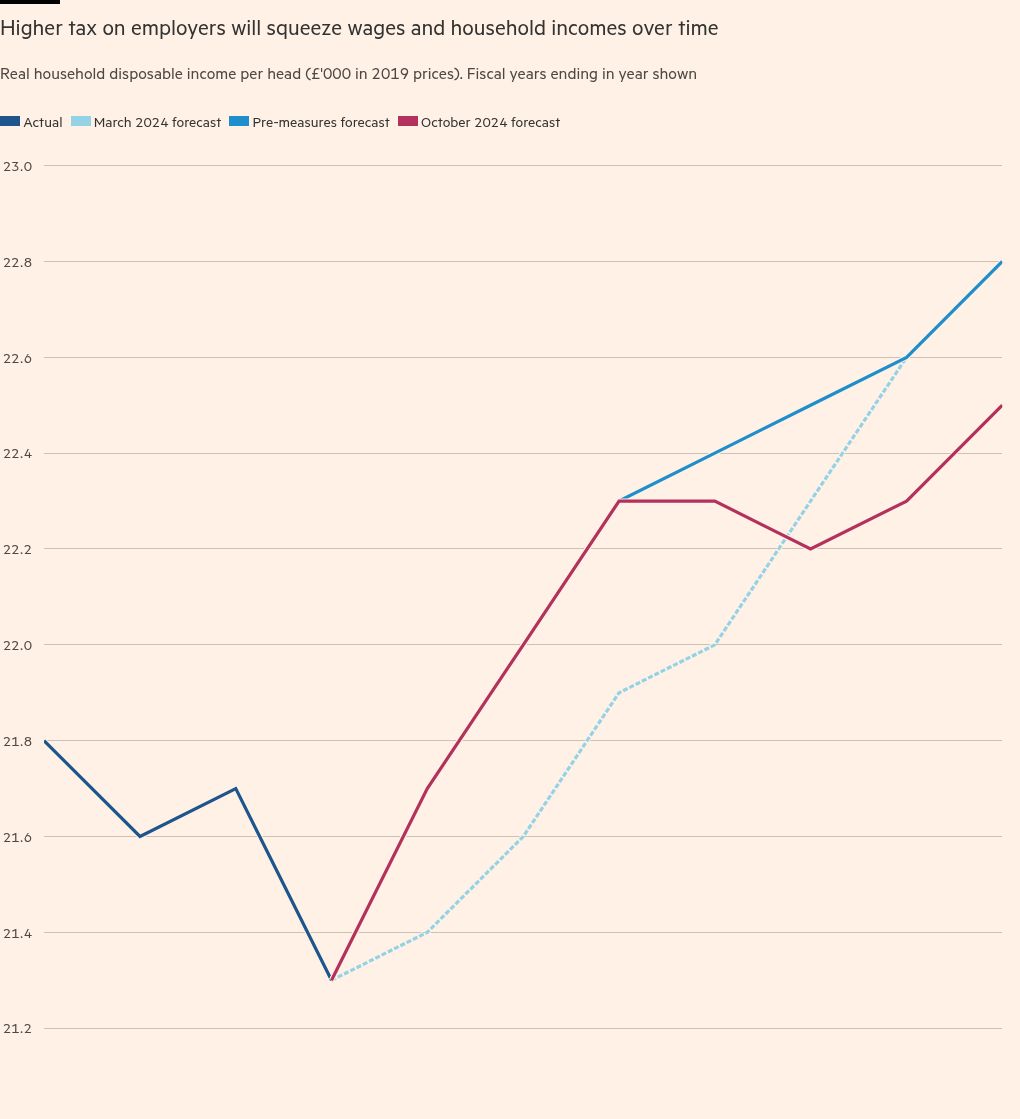

Despite Reeves’ promise to put “more pounds in people’s pockets”, the increase in taxes on employers is expected to eventually be paid by workers — whose wages are likely to rise at a slower pace over time.

Largely due to this, the OBR thinks household disposable income will be around 1 per cent lower after five years than it expected in March and household consumption will be a smaller share of GDP — though as Miles noted, better public services could underpin living standards.

In swaps markets, investors moved to expect three or four quarter-point rate cuts by the BoE over the next 12 months, rather than four or five.

To some economists, Reeves has struck the right balance. Michael Saunders of Oxford Economics said the overall path of fiscal consolidation was now anchored on a more credible footing of specific tax increases, rather than an “implausible and unspecified squeeze” on public spending.

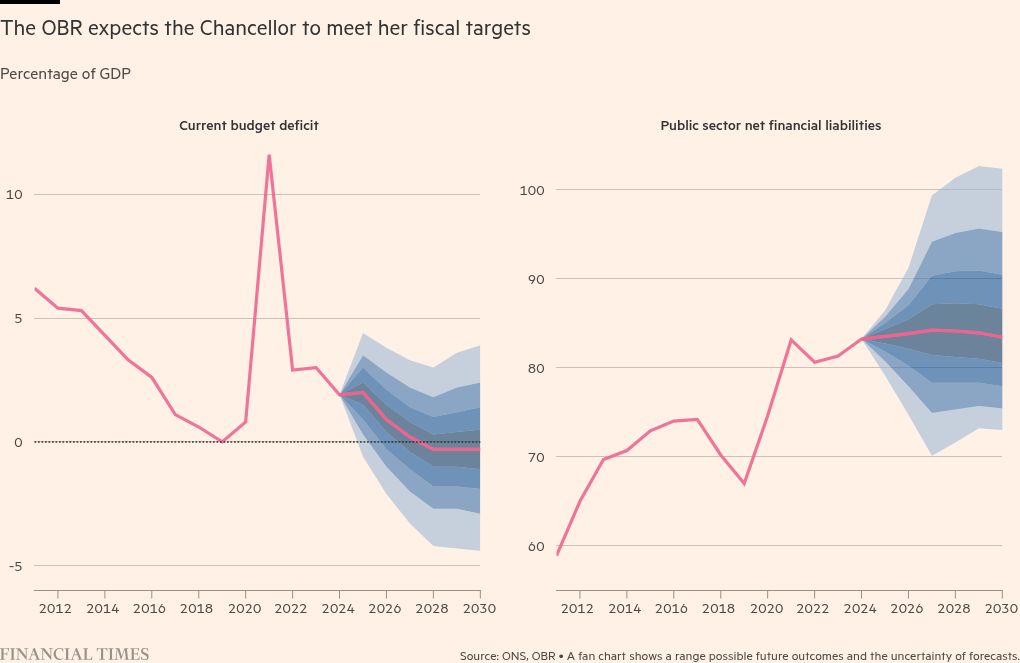

The overall budget deficit may be falling more slowly, but it will still recede from 4.5 per cent of GDP this year to about 2 per cent of GDP in 2029-30.

The new current Budget rule to pay for day-to-day spending with taxes will be met with a narrow margin of £9.9bn in 2029-30, according to the latest forecast.

As expected, the chancellor has softened her debt target in a bid to boost investment, changing the gauge being used to “public sector net financial liabilities”. This target will be met with a margin of £15.7bn.

But the UK’s fiscal arithmetic remains unforgiving. Continued strains on public services could mean that this is not the last time Reeves is forced to tell this parliament she is hiking taxes.

“She may well need to come back with another round of tax rises in a couple of years’ time,” said Johnson. That is, “unless she gets lucky on growth”.