Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of Martin Sandbu’s Free Lunch newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every Thursday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

A lot of ink — and pixel count — has been spilled on the possible minutiae of the upcoming UK Budget, the new Labour government’s first, due to be presented on Wednesday: from how different fiscal rules would give different estimates of the “headroom” available for the government to borrow more to the exact revenue-raising potential of various mooted tax tweaks. Among all that, I fear the debate has lost sight of some of the bigger picture. Regardless of precisely how it does so, will the Budget inaugurate a permanently higher footprint of the British state in the economy? And should it?

There is a broad consensus that the UK economy is broken and that the new government was elected to repair it, both by engineering a higher growth rate and by restoring the public realm and the services of the state to a minimum level of quality.

This implies more spending — both on capital investments and on day-to-day spending. The pre-Budget guessing game has centred on identifying ways in which the government can do this. But more important is really how much money we are talking about.

Take investment spending first. The fiscal plans inherited from the previous government would involve a fall in public investment. As summarised in a report by the Institute for Public Policy Research,

. . . for the UK to merely maintain the level of investment of 2023/24, the government will need to deliver an additional 0.9 per cent of GDP in public investment by 2028/29 (£31bn). And at least another additional 1 per cent of GDP will be needed to fill the UK’s investment gap . . .

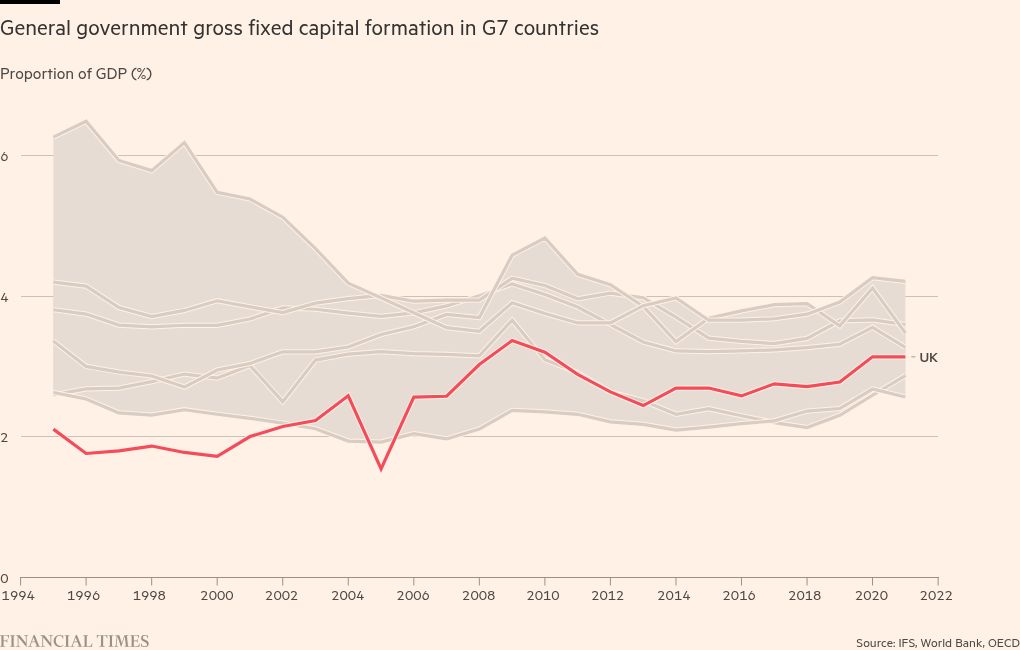

The “investment gap” depends, of course, on what you think total investment should be. The IPPR’s calculations refer to delivering on net zero commitments. But we can also compare the UK with other G7 countries. In the decade to the pandemic, the UK fell short by about half a percentage point of national income compared with the average of its G7 peers. The shortfall was even greater in the decade before that. The chart below shows the Institute for Fiscal Studies’ calculations of public investment as a share of GDP over time:

So just to match its peers, the UK would need to raise public investment by 0.5 per cent of GDP. In order to also make up for past under-investment, something like 1 per cent more of GDP than what the UK has traditionally mustered is not a bad yardstick. Given the investment cuts programmed into existing spending plans, that means aiming for a public investment rate about 2 per cent of national income above where the legacy fiscal plans would have left it.

What about current spending? The government has more or less confirmed (ventriloquising through the Financial Times) how much it will have to go up. Suggested financing needs of about £40bn flow from a combination of an acknowledged £22bn overspend in this fiscal year (but it is unknown how much of that represents a permanent shortfall rather than a one-off), specific spending promises made in the election and anything needed to avoid the “return to austerity” forsworn by Labour.

The IFS has put numbers on different interpretations of that last promise: an additional £16bn by the end of the parliament to spare all public service budgets from real-terms cuts, or an additional £33bn to keep them constant as a share of national income. It also puts at £5bn the cost of specific promises already spelled out, and at £9bn the continuing cost of filling this year’s surprise shortfall. All that could total as much as £47bn a year or 1.5 per cent of national income. And that’s only to keep public services standing in their current sorry state (assuming their costs rise largely in parallel with national income); it would take more to make a noteworthy improvement.

So what we really should be debating is whether the UK could or would change its economic model to one where the state footprint on the economy is more than 3 percentage points greater than today as a share of national income (north of £80bn in today’s money).

The new fiscal rules to be adopted by the government will shape how much of this is financed by new taxes and how much by new borrowing. Additional deficit spending will create a fiscal stimulus and raise public indebtedness. Whether this is appropriate depends on whether you think the economy is too near its potential to tolerate a boost to demand and whether more investment spending will raise the growth rate and hence tax revenues, as Andy Haldane recently argued in the FT.

I tend to be optimistic on both, since I think labour force participation and productivity respond to running the economy hot. You may think differently. Your view — and especially the Bank of England’s view, since that determines how interest rates react — shapes whether we think more public investment will encourage or rather crowd out private investment.

But in the long term, this increase in government spending will surely also involve a significant and permanent rise in the state’s tax take as well as its spending footprint, even if productive investment can and no doubt will be funded mostly through borrowing. (What we should not worry about is that bond vigilantes will send the UK into a funding crisis. Toby Nangle explains why.)

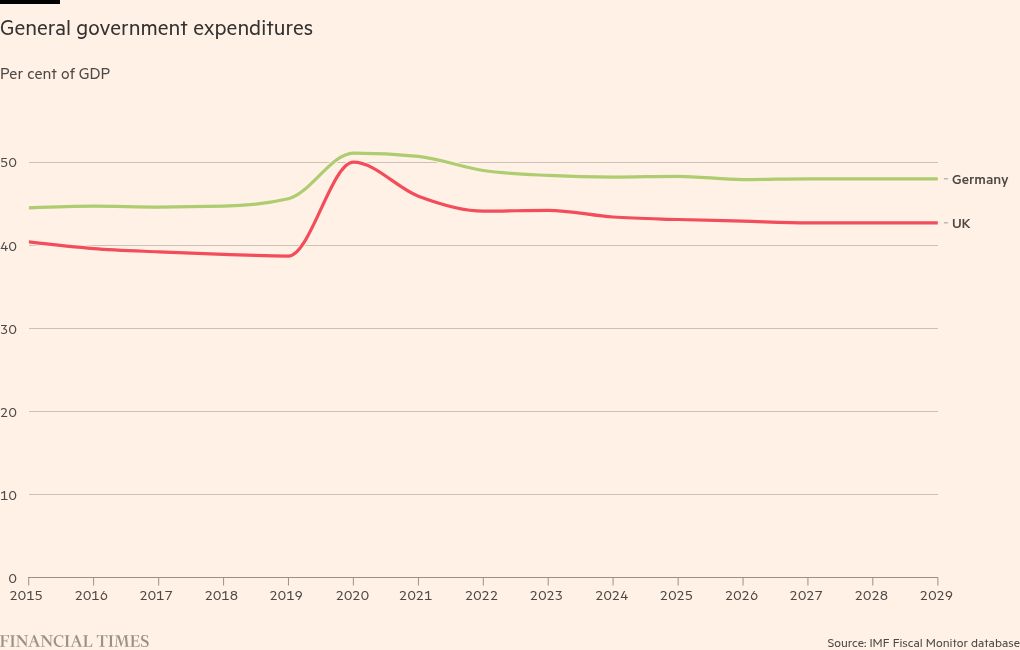

I think the main point to make about this is that it would make the UK less of an outlier in Europe. A change of this magnitude would roughly make the UK look like Germany in terms of the ratio of government expenditure to national income, as the chart below shows.

So the debate that Britain’s political class, and above all its citizens, should have, is whether such a permanent change in the state’s economic role would be a desirable thing.

When asked, both swing voters and voters overall tell some pollsters they would welcome it not just grudgingly but enthusiastically. A new YouGov survey for IPPR and Persuasion UK asked voters how their approval of the government would change if Labour delivered but at the cost of higher taxes or worsened public finances. Three of the biggest improvements in approval rates (all in the tens of percentage points) are lower healthcare waiting times even at the cost of higher national insurance tax; better roads and rail services even at the cost of higher government debt; and somewhat improved conditions in social care and education but with higher taxes on high earners and wealthier households “punishing aspiration”. Other pollsters, however, find a much lower willingness to pay more tax for better public services.

Depending on what people’s real attitudes will be in five years’ time, we may be on the cusp of a revolution of sorts. Since the 1980s, the UK has long taken a bit of a “mid-Atlantic” approach to the state’s role: not as withdrawn as in the US, but not as protective (and expensive) as in continental Europe. The less charitable characterisation has been that British voters want European public services but to pay US levels of taxes. Just perhaps, the UK is leaving that decades-long contradiction behind it — in favour of a more European approach.

Other readables

Recommended newsletters for you

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Your essential guide to money, interest rates, inflation and what central banks are thinking. Sign up here

Unhedged — Robert Armstrong dissects the most important market trends and discusses how Wall Street’s best minds respond to them. Sign up here