Hundreds of North Korean troops have been filmed at military bases in Russia’s far east, training ahead of what Kyiv and its western allies say is a deployment to fight in Vladimir Putin’s war against Ukraine.

Disguised as Buryats and Yakuts, ethnic minorities from Siberia who have made up a disproportionate share of Moscow’s forces, the North Korean troops are part of a 12,000-strong force sent to help Russia retake the Kursk region, partly held by Ukraine since August, according to video footage published by the South Korean intelligence service.

The contingent marks the first foreign army deployment in the war since Russia’s president ordered the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, though Moscow also turned to allies, including North Korea and Iran, for weapons in response to western military support for Ukraine.

Pyongyang has previously supplied Russia with artillery munitions and other weapons, such as the KN-23 ballistic missile, which was accompanied by North Korean officers sent to oversee their battlefield use.

The force is probably too small to turn the tide of the war, as Russia would need to double its 50,000-strong contingent in Kursk to push Ukraine’s troops out and conduct a new wave of mobilisation to make big gains along the Ukrainian front line, according to Ukrainian analysts.

But North Korea’s ability to help make up Russia’s numbers could cause Ukraine more problems, said Jack Watling, a senior research fellow for land warfare at the Royal United Services Institute.

“They might have quite good cohesion. They might have reasonable morale. They might be able to operate at a scale that the Russians struggle to [achieve],” Watling said. “It’s a pretty low bar to be better than what the Russians have at the moment.”

The North Korean reinforcements come amid signs that Russia is struggling to replenish its forces in the face of staggering casualties in Ukraine, which western officials estimate at more than 600,000 killed and wounded.

Putin has resisted pleas from his top brass to order another round of mobilisation, according to western intelligence officials, instead offering enormous bonuses to volunteers for signing up.

FT Edit

This article was featured in FT Edit, a daily selection of eight stories to inform, inspire and delight, free to read for 30 days. Explore FT Edit here ➼

Though that helped Russia maintain a pace of 30,000 recruits a month for most of this year, several Russian regions have drastically increased the size of the payouts in recent months, indicating the army may be struggling to attract more men.

Belgorod region, which borders Kursk, raised its signing bonus for recruits threefold from Rbs800,000 ($8,300) in August to Rbs3mn in October — a life-changing sum when the average monthly wage in the region last year was Rbs55,000 ($570).

The domestic struggles have prompted Russia to bolster its forces from abroad, the western intelligence officials said. “North Korea is Russia’s new best friend,” one of the officials added.

Though Russia is likely to run into obvious command and control issues, its experience leading operations with government troops, Iranian-backed forces and militias in Syria’s civil war would give Moscow’s command an obvious model to build on, Watling said.

The troops being sent to Russia are from North Korea’s Eleventh Army, an elite unit known as the “Storm Corps”, according to South Korea’s National Intelligence Service.

“These are not ordinary North Korean soldiers, most of whom are never given adequate combat training,” said Go Myong-hyun, a senior fellow at South Korea’s state-affiliated Institute of National Security Strategy in Seoul. “These are well-equipped, highly trained mobile light infantry.”

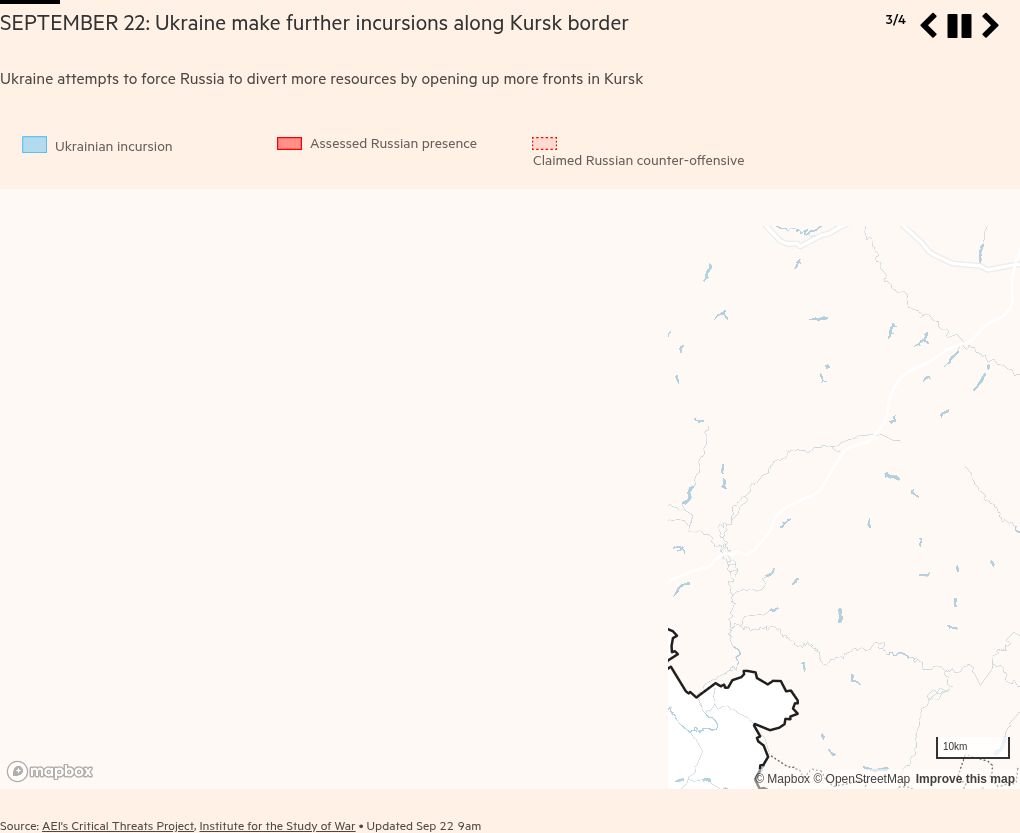

The North Korean forces will arrive just as Russia has pushed back Ukraine’s army in Kursk, shrinking the amount of land it holds to between 600 sq km and 700 sq km in October from about 1,000 sq km in late August.

Unlike the Ukrainian front line, where troops defend and attack from established positions, in Kursk region the front line has not been defined. This means Russia cannot use its most tried and tested methods: rolling infantry attacks, accompanied by constant artillery.

But Russia is making use of its air power advantages in Kursk region by air-bombing its own villages where they detect a Ukrainian presence, forcing those soldiers to flee.

“Every position and settlement there can change [hands] several times a day,” said Serhiy Kuzan, director of the Ukrainian Security and Cooperation Center in Kyiv. “We have significant losses . . . We also have constant rotation and replenishment, and given that this is happening, we can judge that the fighting is quite intense,” said Kuzan, who recently visited Ukrainian rear positions overseeing the operation from Sumy, just across the border.

Russia’s objective was to force Ukraine into a position where holding the width of the front was untenable by pressuring it across several different points along the line, Watling said.

“There is a continual cost for Ukraine holding that territory” in Kursk region, he added.

The North Korean deployment cements blossoming ties between Moscow and Pyongyang since the war began. Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un signed a treaty in June that includes a mutual assistance clause promising “immediate military and other aid” in the event of war. North Korea was also the first of only two countries, alongside Syria, to have recognised Russia’s partial annexation of four front-line Ukrainian regions in the fall of 2022.

Kim had “always wanted” to deploy troops to Ukraine, said Go, as it would give him greater leverage over Moscow and potentially allow him to access sophisticated Russian military technologies to boost his ballistic missile, space and nuclear programmes.

Moscow could reward North Korea with much-needed finances, food and fuel, or deepen its partnership with the isolated communist state by transferring advanced weaponry, according to Alexander Gabuev, director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center in Berlin.

That could include transferring advanced weapon designs, co-operation between Russian and North Korean scientists on missile technology and undersea warfare.

The threat could prompt South Korea to raise its support for Ukraine in retaliation, Gabuev added. Seoul has resisted entreaties from western partners to supply weapons to Kyiv amid fears that Russia would respond by offering advanced defence-related technologies to Pyongyang.

Aside from modest donations of non-lethal military and humanitarian aid, Seoul has limited its assistance to replenishing US stocks of 155mm artillery shells sent to Ukraine.

But on Tuesday, a presidential official told South Korean state media that Seoul would consider sending Kyiv defensive weapons, “and if a threshold is exceeded, we could ultimately consider offensive weapons as well”.

In addition to 105mm and 155mm artillery shells, that could mean Kyiv also receiving stocks from South Korea’s formidable arsenal of howitzers and antimissile systems, among other military hardware.

South Korea would also probably simultaneously step up covert diplomacy with China, Russia and North Korea’s most important partner, in an attempt to push back against any transfers of advanced weaponry, Gabuev said.

“China has been signalling that it’s not very happy about the deepening of North Korea-Russian military ties,” Gabuev said. “South Korea can definitely make a case with China that it will step up co-operation with the US on the Korean peninsula if China doesn’t address this problem.”

North Korea’s ultimate goal in sending troops, however, would be to secure a Russian commitment to intervene on its side in any conflict on the Korean peninsula, dramatically transforming concepts of how a war there could play out, Go said.

“Just a few years ago Russia was at least nominally committed to enforcing UN sanctions on North Korea” over its nuclear programme, he said.

“Everything that South Korean and US military planners assumed in terms of how a conflict on the peninsula might play out will have to be rethought.”

Cartography by Steven Bernard