Youth centres were closed long ago. Then libraries and bus services felt the squeeze. Now, in the southern English county of Hampshire, highway maintenance is being cut, street lighting rationed and the “lollipop” ladies and men who protect schoolchildren from traffic will soon be a thing of the past.

Although it runs a relatively prosperous area, Hampshire’s Conservative-led council, like most local authorities in England, is facing an attritional fight against insolvency as the rising cost of child and adult social care — which it is legally bound to provide — swallows up funding for everything else.

The death rattle for other services was sounding this month as the council cabinet met in Winchester to vote on savings towards bridging next year’s shortfalls.

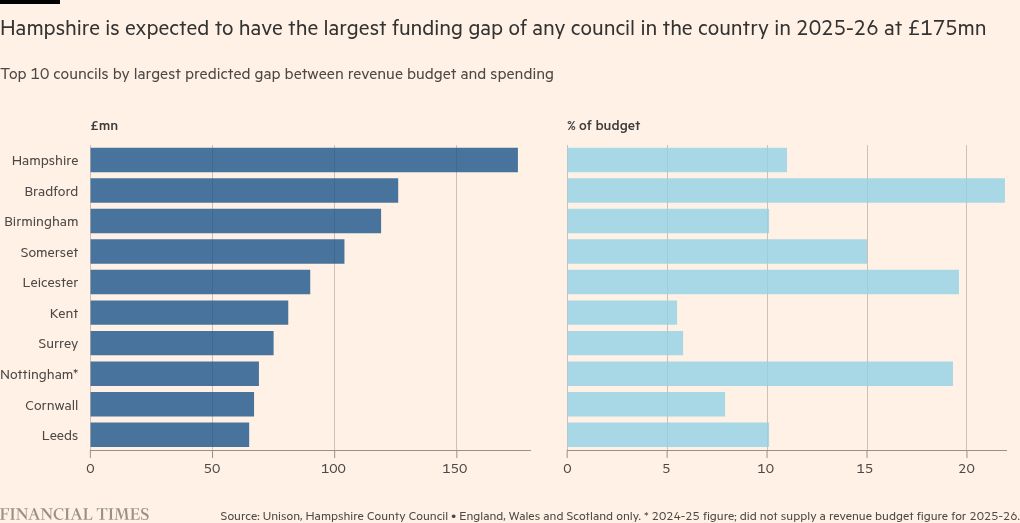

Unison, the union, last month forecast that Hampshire’s budget deficit would be the biggest in the country in 2025-26, at £132mn against a revenue budget of £1.2bn, though other local authorities are worse off in proportion to their revenue.

The council has since increased its forecast deficit to £175mn because demand and costs have continued “to rise more than anticipated in children’s and adults’ social care, special educational needs and school transport”.

“We are not at the cliff edge yet. Others will go over first, but there is a big weight dragging us towards it,” said council leader Nick Adams-King.

When the Conservatives were voted out in Westminster elections in July after 14 years, they left England’s 317 councils in varying degrees of financial distress.

Grants from central to local government were down more than a third in real terms compared with 2010. Meanwhile, ministers repeatedly postponed tough decisions on the way social care is funded, council tax set and finances distributed around the country.

Eight councils have gone bust since 2018, and this year an unprecedented 18 are receiving emergency financial assistance. This comes in the form of capitalisation directions — local government speak for life support — when Westminster allows councils to flog assets and use other capital resources to pay for day-to-day spending.

In the meeting Adams-King chaired, the cabinet had little choice but to vote for more cuts. Services for homelessness, which is at all-time highs nationally, were spared. But waste recycling centres, libraries, highway maintenance, school traffic controllers, cultural and community grants, street lighting and winter services such as gritting roads will all be sliced.

“The cost pressures from statutory services are so high that even this may not be enough to get the budget to balance on a sustainable basis,” Adams-King wrote in a despairing letter to Rachel Reeves later in the week.

With the chancellor painting a dismal fiscal picture ahead of the Budget on October 30, local authorities, which meet in Harrogate for their annual conference this week, are not expecting much of a rescue package.

The one measure the government has promised is longer-term funding settlements to give councils more time to plan. The Treasury declined to comment on Budget speculation but the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government said longer-term financial arrangements would provide “greater stability” and help end “competitive bidding processes for pots of funding”.

Local officials have welcomed that pledge, but warn that much more is needed.

Noting that the cuts agreed in Hampshire would only get the council halfway towards balancing the budget next year — with the rest having to be drawn from reserves — Adams-King implored Reeves to prioritise reforming local government finance if vital services were to survive.

Keith House, Liberal Democrat opposition leader on the council, said the same. “This government might get away with it, for another year, giving some pots of money for those councils going under,” he said. But without a more radical fix Labour would preside over an accelerating number of bankruptcies beyond 2025-26, he added.

The Local Government Association has called on Reeves to deliver a “sustained increase in overall funding that reflects current and future demands for services” and that bridges the £6.5bn black hole it forecasts across all councils to 2027.

In the longer term, the representative body wants government to stop dictating where grants are spent, and to carry out a “fair funding review” promised since 2016 on where they are allocated.

Among more radical ideas, the cross-party think-tank Demos will this month propose in a paper that councils be stripped of responsibility for adult and social care and homelessness. Under its plans, these would be organised under devolved regional trusts — similar to the NHS, but with financial risk borne at the central government level where resources can be pooled.

Andrew O’Brien, policy director at Demos, said such a change would end the “fiscal fiction” that made local government legally responsible for delivering social care and a host of other services but left it dependent on Whitehall to do so, and on resources that were rarely matched to geographic demand.

“Just restoring central government grants isn’t going to fix the system,” he said. “One solution is to take financial responsibility for adult and child social care and homelessness away from local authorities”, allowing them space to focus on other neglected roles.

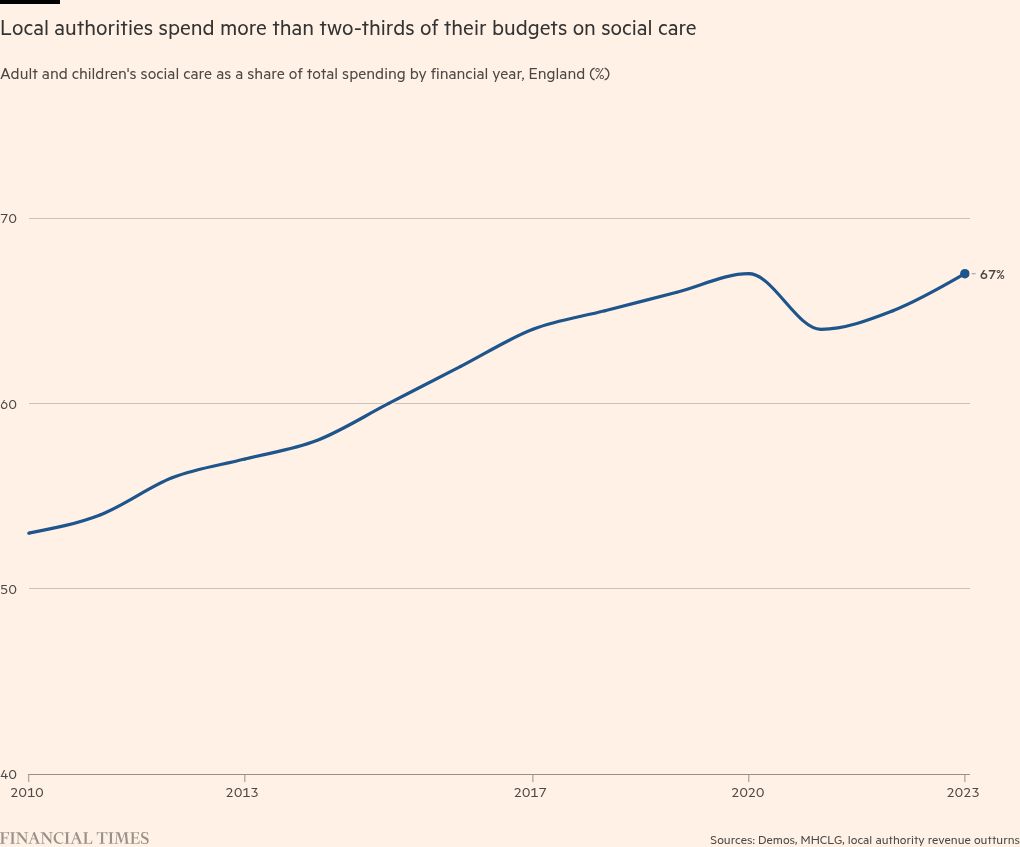

Across all local authorities, spending on adult and child social care has increased from 53 per cent of expenditure in 2009-10 to 66 per cent in 2022-23, according to Demos.

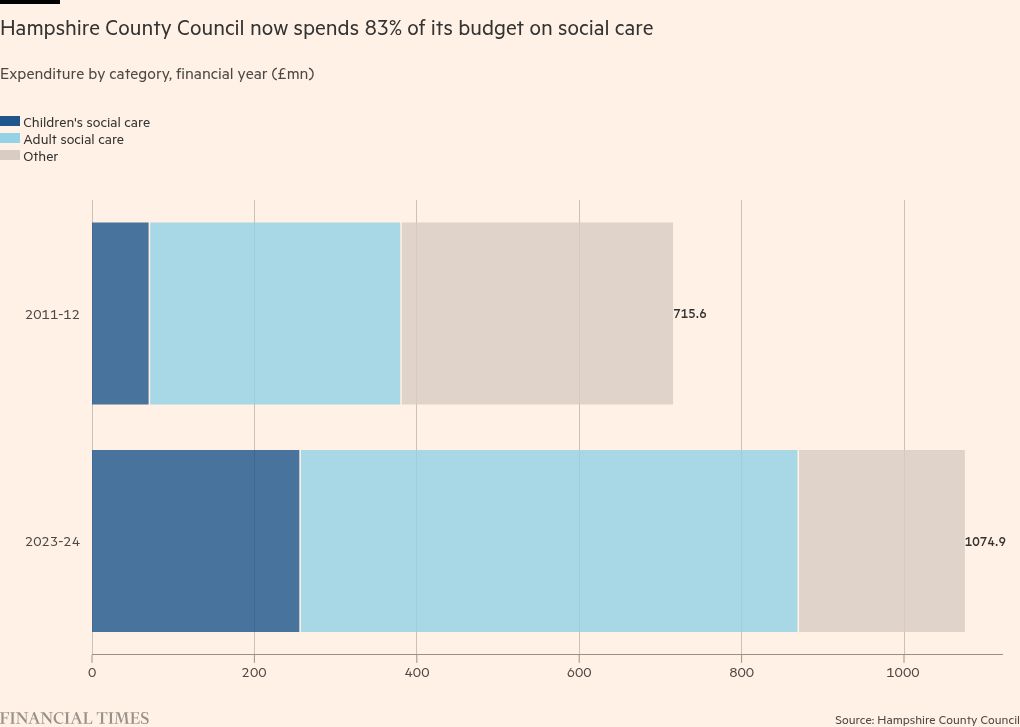

In Hampshire, which is among the top four counties in terms of concentration of wealth, the figures are starker still: funding to the council from Westminster is down 46 per cent since 2011. The cost of providing adult and child social care has soared from £381mn in 2010-11, or 53 per cent of the budget, to £809mn this year, or 83 per cent. Hence the painful cuts.

“None of us want to be making these decisions. We find ourselves here because of the way local government finance is structured. I hope this government might change that,” said Adams-King.