This First Person column is the experience of Amy Reiswig, who lives in B.C.’s Gulf Islands. For more information about CBC’s First Person stories, please see the FAQ.

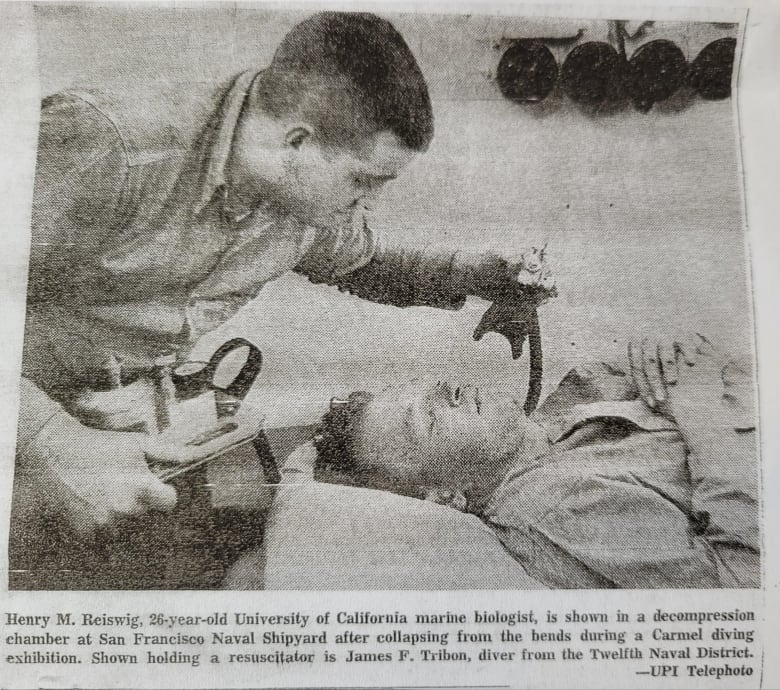

I first encountered Jim Tribon in a newspaper photo tucked into a scrapbook I’d found among my father’s belongings.

The picture was taken through a porthole of the decompression chamber at a San Francisco naval shipyard in 1962. It showed my father, lying unconscious, and a U.S. navy diver holding a resuscitator over his face.

Long before I was born, my dad had a near-fatal diving accident, and it was part of our family lore. My mother, who was his girlfriend when it happened, had told us that almost losing him made her realize how much he meant to her.

But for the first time, I was seeing the face of a man who’d helped save dad’s life, in turn making my life possible. The faded caption told me his name.

I wondered if this James F. Tribon, unlike my father, was still alive. Expecting nothing, I looked him up, found his email through the Navy Divers Association and wrote.

“I hope this doesn’t strike you as a strange email out of the blue,” I began. And I soon received a very surprised reply.

Evidence of dad’s brush with death

I knew my dad, a marine biologist, as an unsentimental scientist. Seeing the scrapbook among the ephemera that he’d held onto was unexpected. Like the ocean he loved, he had depths not often seen.

The stiff pages of mounted photographs from the ’50s and ’60s showed a young man in his element, scuba diving and spearfishing with his buddies.

When the newspaper photo was taken, both dad and Jim — who didn’t know each other — were strong men in their 20s. Nonetheless, the image made me shiver.

I saw an intimate portrait of vulnerability and care; that made dad’s brush with death all the more real.

In it, I also saw how close I came to not existing and was reminded of the thin separation between being and not being. Did this man help make the difference?

Often, the random connections that make life happen go unseen, but here was one frozen in time right in front of me.

A date with a stranger

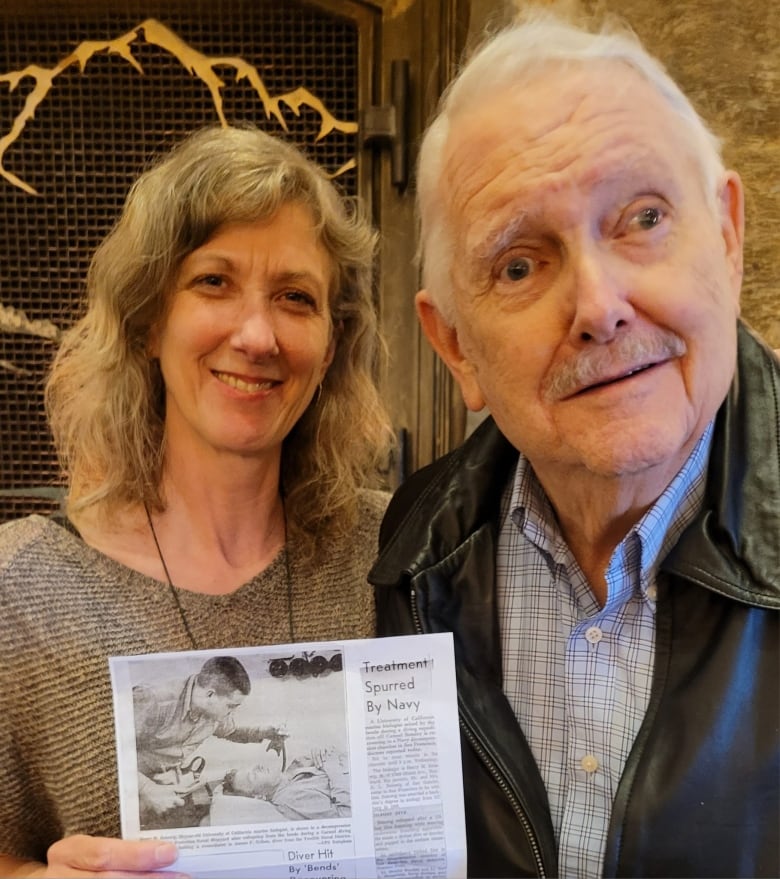

June 4, as I sailed from my small island to the B.C. mainland, was a day of rough seas in every way. Like the choppy waves rocking the boat, my emotions were a churn of excitement and nervousness. I’d reached out to a total stranger, a man in his 80s, who was driving 160 kilometres from Washington state just to meet me. What if there wasn’t much to talk about? What if he felt like he wasted his time? Was I being overly sentimental, making more of this tenuous connection than I should?

At the Tsawwassen ferry terminal parking lot, Jim stiffly unfolded his tall frame from a blue-and-white Cadillac. Despite my rain-wet jacket, there was a big hug.

During our talk, Jim told me what he remembered from that day 62 years ago. He and dad hadn’t had further contact, but I had brought a copy of the clipping. We looked at his young self and went back in time together.

Jim was keen to clarify that while the newspaper said my father had the bends — or decompression sickness — the bloody froth at dad’s mouth indicated an embolism. And he told me that most people who experience an embolism don’t come out alive. “They come out dead.” The impact of Jim’s care suddenly took on even greater weight.

I also heard about Jim’s navy career, including tours in Vietnam and a then-secret submarine recovery project for the CIA. I learned that much of his work involved rescuing things — sunken seaplanes, torpedoes, mines, bodies.

But he never knew what he helped create through his role in the much-smaller rescue of my dad that day.

“This is us camping,” I said, passing him photos from my childhood. “This is me and my dad on New Year’s. And here’s our old house in Montreal: my dad, mom, sisters and me.

“None of this would exist if dad had died that day,” I told him, smiling but near tears.

The human web: invisible and strong

I wanted Jim to understand, as I now did, how he’d played a part in my father’s touch on the world — the students he taught, scientists he mentored, discoveries he made, children he loved.

As Jim carefully examined each of the photos, he told me that he’d never imagined the ripple effects of what happened that day in August 1962. “I was just doing my job.”

I had initially reached out to Jim seeking a gift of connection for myself: to thank him in person and have even a brief living connection to my dad again. But as I sat there, watching Jim’s face, I realized this meeting offered gifts for us both, highlighting the importance of letting people know the impact they’ve had, the reverberations they’ve unknowingly made.

We can never know exactly whose touch is on our lives. The human web is often invisible but strong, and just going about our lives and work can have potentially life-altering consequences. We all matter in ways we might never know.

Do you have a compelling personal story that can bring understanding or help others? We want to hear from you. Here’s more info on how to pitch to us.