This article is an onsite version of our Europe Express newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday and Saturday morning. Explore all of our newsletters here

Welcome back. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy of Ukraine this week unveiled a five-point “victory plan” for the war against Russia. Even from Ukraine’s western friends, the plan didn’t receive unqualified support.

One way of approaching this topic is to turn matters round and ask: will Russia prevail in the war, and what would constitute “victory” for President Vladimir Putin? I’m at [email protected].

Zelenskyy’s plan

Zelenskyy’s initiative had five main components, summarised here by the BBC:

-

Joining Nato

-

Strengthening Ukraine’s defences and securing western support to use long-range weapons in Russia

-

A non-nuclear, postwar deterrent to contain Russia

-

Joint Ukrainian-western exploitation of Ukraine’s natural resources

-

A Ukrainian contribution to the west’s defences after the war

Mark Rutte, Nato’s new secretary-general, gave a guarded response to Zelenskyy’s plan:

The plan has many aspects and many political and military issues we really need to hammer out with the Ukrainians to understand what is behind it, to see what we can do, what we cannot do.

Some Ukrainian politicians were not convinced, either. Opposition lawmaker Oleksii Honcharenko said:

“It’s kind of a wish list from Ukraine for our partners . . . And it doesn’t look realistic.”

One large, unanswered question about the plan is whether an end to the war would leave Russia occupying the roughly one-fifth of Ukrainian territory that it now holds.

The plan contains annexes, not made public, that may address this point. Clearly, territorial control would lie at the heart of any negotiations, no less than Ukraine’s postwar security.

For the moment, I think we can assume that neither Ukraine nor western governments are inclined to cede formal, legal control over the occupied territories to Russia.

A truncated but successful Ukraine?

It isn’t difficult, however, to imagine an end to the fighting that leaves Russia in de facto control of Crimea and much of south-eastern Ukraine.

Thomas Graham, writing for The Hill, explains:

Most western governments now acknowledge privately, if not publicly, Ukraine is not likely to drive Russian forces from all the Ukrainian land they have seized since 2014.

For Graham, the key point is how a truncated Ukraine would develop after the war. Would it revert to “the poor, corrupt, oligarchic country of little interest to the west” that it was before the 2014 Maidan revolution?

Or would Ukraine emerge as “a strong, prosperous, democratic, independent country” anchored in western institutions?

Framing the issue in this way clarifies the question of what would amount to victory for Russia.

Control of territory: far from the only issue

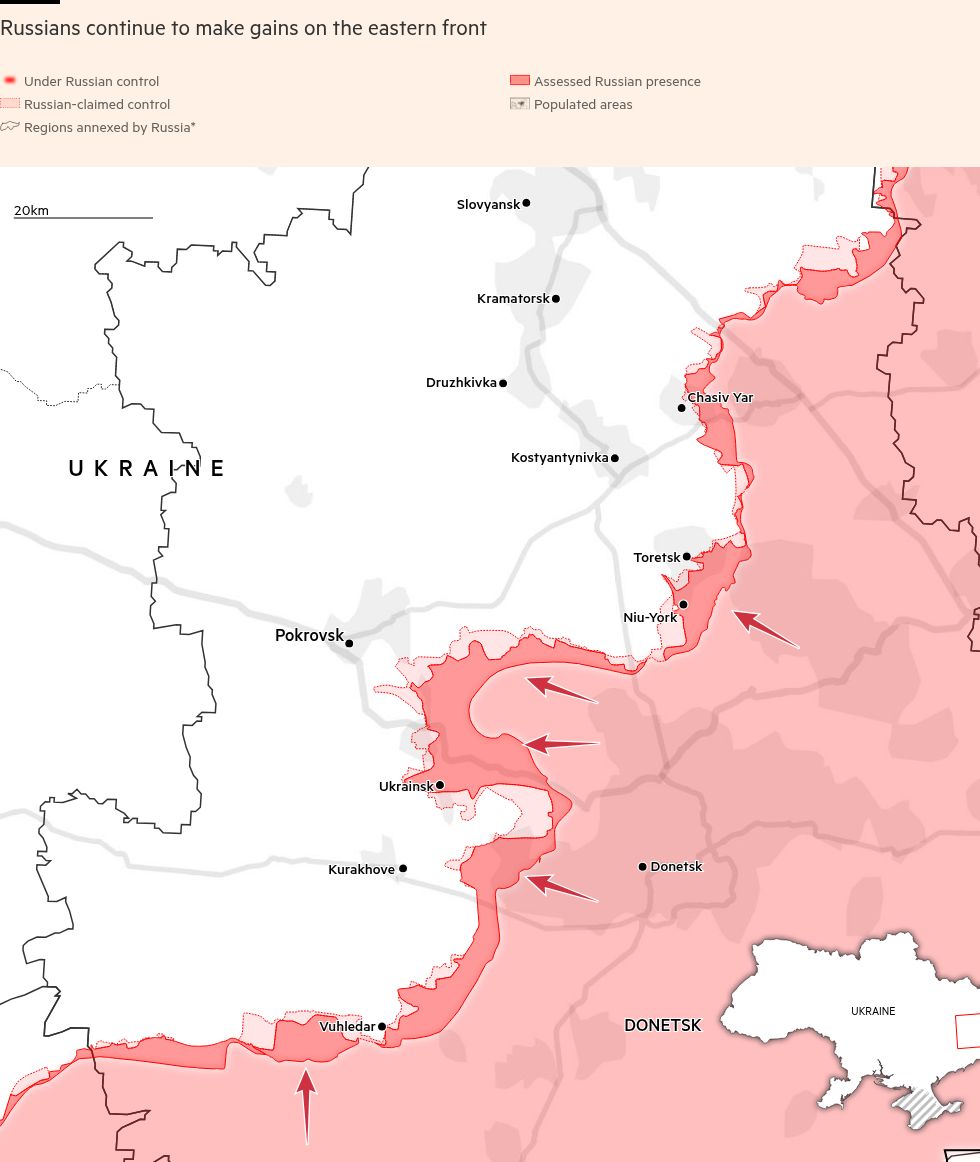

Viewed in purely territorial terms, Russia’s war aims are to retain Crimea and the four eastern regions over which Moscow proclaimed its sovereignty in 2022.

However, even after the gradual advances of Russia’s armed forces in the east this year, the Kremlin does not fully control these four regions. It follows that an end to the fighting that froze the battle lines more or less as they are now would not completely fulfil Russia’s territorial war aims.

But the picture is much bigger than who controls what chunks of Ukrainian land.

Putin launched his full-scale invasion in February 2022 under the pretext of demilitarising and “de-Nazifying” Ukraine. Put differently, his aim was to destroy the independent Ukrainian state that emerged in 1991 out of the rubble of the Soviet Union, and to discredit the very idea of a Ukrainian national identity separate from that of Russia.

The historian Thomas Otte, writing in March 2022, captured this point brilliantly:

Putin’s views . . . reflect his embrace of the fundamentally anti-western, anti-European concept of russky mir [the Russian world], a partly historical, partly ideological construct that draws on the idea of “holy Rus” of the 10th century – itself an “invention” of 19th-century historians.

It encompasses late tsarist ideas of an ethnocultural pan-Slav bond between the eastern Slavs, and it is fuelled by memories of victory over fascism in the “Great Patriotic War” [the second world war].

Looked at from this angle, Russia has already fallen short of its aims. Ukraine’s national identity has been forged in the fires of war and cannot now be subsumed into some nebulous Russian-dominated east Slav brotherhood.

Furthermore, even a dismembered Ukraine would remain a functioning state and part of the international system. Still, as Graham says, it would have to continue along the road of internal reform and would need credible guarantees of western protection.

Building Brics

Putin’s ambitions, stimulated by the Ukraine war, also encompass a revision of the world order in favour of Russia and its sympathisers, and to the disadvantage of the US and its allies.

How is that going?

Next week, leaders of about two dozen countries will meet in Kazan, capital of the Russian region of Tatarstan, for a summit of the Brics club.

Gleb Bryanski writes for Reuters:

The Oct. 22-24 summit . . . is being presented by Moscow as evidence that western efforts to isolate Russia have failed. It wants other countries to work with it to overhaul the global financial system and end the dominance of the US dollar.

However, even some Russian commentators sound cautious about the usefulness of the Brics group, which has expanded beyond its original membership of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

Fyodor Lyukanov, editor-in-chief of the journal Russia in Global Affairs, says that, from Moscow’s viewpoint, it is positive that “the west’s ability to determine the entire global situation is rapidly disappearing”.

But, with regard to the Brics group of existing and aspiring members, he adds:

The difficulties are obvious. With such a number of completely different states with different cultures, different interests, different levels of development, finding a consensus, a common denominator is extremely difficult. And the more states, the more difficult.

Iran, North Korea and China

In some respects, Russia has found it more beneficial to expand co-operation with Iran and North Korea, which are explicitly anti-western in a way that isn’t true of Brics countries such as Brazil and India.

This month, Putin met Masoud Pezeshkian, Iran’s new president, in Turkmenistan (the FT’s Charles Clover and Najmeh Bozorgmehr wrote a good piece on the military dimensions of the Russian-Iranian relationship).

How close are Russia and Iran? Perhaps less close than meets the eye.

According to Tatiana Stanovaya, an independent Russian political scientist, the Kremlin remains reluctant to share military, space and especially nuclear technology with Iran.

Trade volumes between Russia and Iran fell last year, underscoring the mistrust of Russian businesses towards their Iranian counterparts, she says.

As for North Korea, ties with Russia have unquestionably deepened the longer the Ukraine war has gone on. Putin visited Pyongyang in June and signed a “comprehensive strategic partnership pact” with Kim Jong Un.

However, in this piece for the Stockholm Centre for Eastern European Studies, Hugo von Essen comments:

[The partnership] could . . . have serious negative impacts for both China and Russian-Chinese relations. These include a destabilised Korean peninsula, greater US attention and resources spent in the region and a strengthened US-Japan-South Korea trio.

With regard to Russia’s relationship with China, let me highlight for you this excellent analysis by Eugene Rumer for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

He points out that Moscow and Beijing have much in common — authoritarian domestic politics, tensions with the US. But he stresses that they do not see eye to eye on everything and that, during the Ukraine war, the relationship has tilted in China’s favour.

Russia’s militarised economy

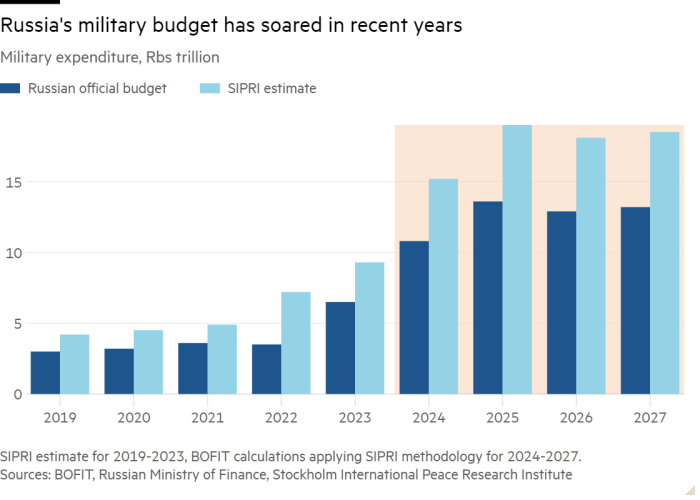

Finally, some thoughts on Russia’s war economy. As Bank of Finland analysis in the chart below shows, military expenditure is soaring:

But few topics more sharply divide western commentators than the prospects for the Russian economy.

On one hand, some specialists emphasise Russia’s resilience and the limited effectiveness of western sanctions. Wolfgang Münchau, writing for the New Statesman, comments:

“The Russian war economy is running on steroids and generates huge revenues for the state.”

On the other hand, Anders Åslund, a longtime Swedish expert on Russia’s economy, says:

“My own view is that the current sanctions regime shaves off 2-3 per cent of GDP each year, condemning Russia to near stagnation.”

He makes the interesting point that Russia’s central bank, whose main interest rate stands at 19 per cent, estimated annual inflation in August at 9.1 per cent. Åslund says:

“Nobody should believe such figures. Most likely, the authorities are repacking inflation as real growth.”

My own view is that, whatever Russia’s difficulties and manipulation of data, an end to the fighting in Ukraine is likely to arrive sooner than a breakdown of the Russian economy.

What do you think? Will Russia win the war? Vote here.

China and Russia’s strategic partnership in the Arctic — a commentary by Paul Goble for the Jamestown Foundation

Tony’s picks of the week

-

As much as two-thirds of the EU’s water bodies are in bad condition, according to the European Environment Agency, the FT’s Alice Hancock and Alan Smith report

-

One year on from October 7, Palestinians face their most severe crisis in 75 years but have no unified leadership to guide them, Omar Rahman writes for the Italian Institute for International Political Studies