This article is an on-site version of our Moral Money newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered three times a week. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters.

Visit our Moral Money hub for all the latest ESG news, opinion and analysis from around the FT

Welcome back. At a breakfast hosted by Morningstar Sustainalytics yesterday in London, analysts cautioned against inflated expectations for next week’s COP16 UN biodiversity conference in Colombia.

“This is probably the third year in a row where we’ve been expecting a big breakout moment for biodiversity investing,” Lindsey Stewart, director of stewardship research, told attendees. However, he predicted, “we’re not going to be quite at that big breakout moment yet”.

Morningstar has identified just 34 equity funds or ETFs focused on biodiversity — all of them in Europe — that represent just $3.7bn in assets, said sustainability research head Hortense Bioy. That’s compared with $530bn in climate funds and ETFs Morningstar tracks globally. There was one biodiversity fund in the US, Bioy said, but it closed.

Meanwhile, with Moral Money Americas under way today in New York City, I have a story that bucks a persistent narrative that developing countries are energy transition laggards. — Lee Harris

renewable energy

In poorer nations, renewable power is getting its moment in the sun

For years, the buildout of solar and wind power in the developing world has lagged behind richer nations. Renewables’ high upfront capital costs have held back investment, even though many countries in the global south are sunny, energy-hungry, and less burdened with legacy fossil fuel infrastructure.

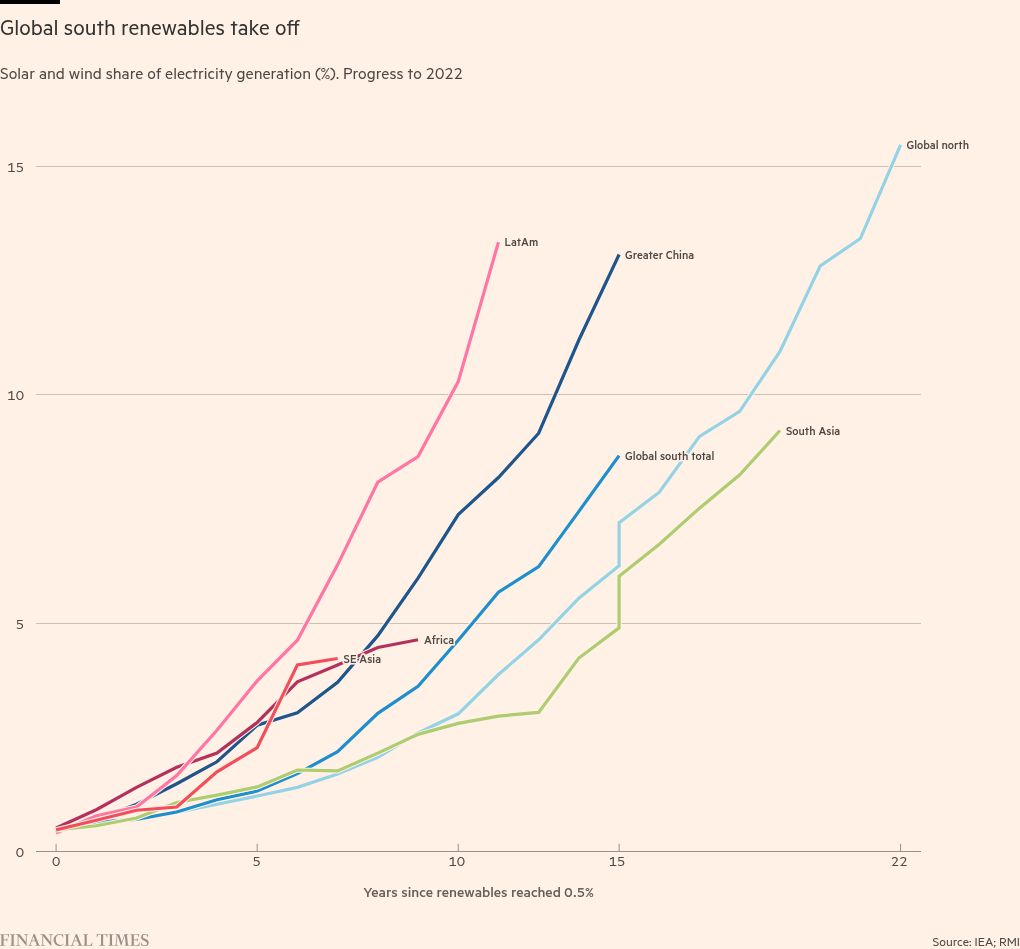

But renewables in many emerging markets are now achieving lift-off. Solar and wind power, measured both by energy generated and as a share of total electricity generation, is growing faster in the global south than in the global north, according to a new study by energy consultancy RMI.

Over the past five years, renewable energy generation has grown at a compound annual rate of 23 per cent in the global south, versus 11 per cent in the world’s richest economies. RMI defines the global south as Africa, Latin America, south and south-east Asia, and excludes China and the major fossil fuel exporters in Eurasia and the Middle East.

Seventeen per cent of energy demand in the global south comes from countries where the solar and wind share of electricity generation is higher than that in the world’s richest economies. These countries include Mexico, Brazil and Morocco.

Importantly, these findings compare rates of growth, not total generation capacity installed. (This makes sense, since many developing countries started their energy transitions more recently, and are therefore starting from a lower base.) While the global south is not yet adding more renewable power than rich economies in absolute terms, RMI expects that trend to flip by the end of this decade, largely due to the drastic cost decline in renewable technology.

“Even with the lack of commitment from the global north, in terms of their funding for the global south, this technology is very much in the money,” RMI report co-author Vikram Singh told me. “It’s boom time in the global south” for green energy, he said.

The bullish projections are due, first and foremost, to Chinese investment in renewables, which has created economies of scale that are making these technologies more affordable globally. The cost of solar and battery technologies halved in 2023, RMI said, making them cost-competitive in middle-income markets such as Brazil and India.

But disparities in the cost of capital haven’t evaporated. Investors continue to ascribe higher risk to the global south. In 2022, the weighted average cost of capital for a 100-megawatt solar project in South Africa, Vietnam, Brazil or Mexico was about 11 per cent, while in advanced economies it was about 5 per cent, according to the International Energy Agency.

Where the global south’s solar boom has arrived, it is despite development banks’ failed promise to deliver trillions more in blended public and private-sector finance for sustainable development.

Despite those persistent challenges, Singh said, “I don’t think that the narrative is any longer that the global south is begging for global north dollars and intervention.”

In Vietnam, solar energy will hit “capex parity” in 2024 with coal, RMI found using BloombergNEF data, meaning that the upfront cost of solar buildout will be equal to that of coal.

Some regions have even outpaced China’s rate of renewables penetration. Latin America hit the same share of electricity generation from solar and wind as China — and grew more quickly after securing an initial foothold where it provided 0.5 per cent of generation.

It’s not only falling costs that are driving deployment. The global south could actually achieve a faster energy transition than richer economies, RMI argues, for a few reasons:

-

Richer countries went first: By installing solar and batteries when they were more expensive, more developed countries ate some costs and ironed out the kinks in deployment.

-

More sun: Many developing countries are closer to the equator, meaning more intense sunlight.

-

Less steel in the ground: Many emerging markets have less legacy fossil fuel infrastructure to deal with — and less of an entrenched fossil fuel lobby.

Finally, RMI thinks the global south has a geopolitical edge in the transition: developing countries are more open to sourcing the cheapest renewable technologies, which overwhelmingly come from China. By contrast, trade tensions could drive up the cost of the transition in the west.

EU member states agreed earlier this month to impose tariffs of up to 45 per cent on imports of Chinese electric vehicles, and the US has said it plans to raise its own tariff to 100 per cent.

Efforts to block Chinese technologies such as EVs are “unfortunate”, Singh said, since they “take away from competition and further growth of the sector”. Plus, he said, they made it more likely that China would supply the next generation of energy technologies to the global south.

Further challenges await. In addition to commitments to deploy new clean energy at the UN’s COP conference in Dubai last year, countries also pledged to double energy-saving efforts by 2030. Without focusing on efficient use of energy, Singh said, we are pouring more energy supply into “a leaking bathtub”.

Smart read

Global insurers are almost universally opting to include a low-carbon transition goal in their investment plans, Brooke Masters reports.

Recommended newsletters for you

FT Asset Management — The inside story on the movers and shakers behind a multitrillion-dollar industry. Sign up here

Energy Source — Essential energy news, analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here