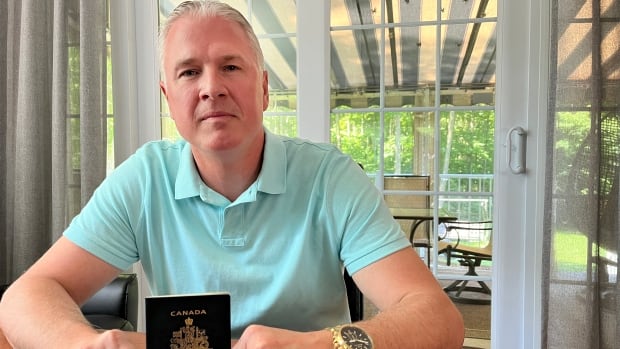

Quebecer Danny Roy is a travel enthusiast and the United States is one of his favourite destinations.

But for him, crossing the border is no easy task.

He is regularly intercepted and questioned because he is mistaken for a namesake with a criminal past.

Things went south in the summer of 2022 when he showed up with his family at the Jackman border crossing in Maine, on the border of Beauce, Que. Roy says he was asked to get out of the car and to go inside, where an interrogation began.

“Where do I live? What do I do for a living? And do I have tattoos?” are among the questions Roy told Radio-Canada’s La facture he was asked.

After a 30-minute interrogation, he said he was allowed to enter the country.

Roy has a valid passport and no criminal record. But because he has one of the most common last names in Quebec, he suspects that customs officials have confused him with one of his namesakes who have had run-ins with the law, some more serious than others. One of them pleaded guilty with involuntary manslaughter.

“No matter how serious the offence, if you have a name that is similar to someone with a criminal record, you will be checked, perhaps even prevented from entering the United States,” said Michel Juneau-Katsuya, a border security expert and former investigator with the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS).

After that first mishap, Roy had an official document made with the seal of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), certifying that he had no criminal record.

This paper, which initially gave him a sense of security, ultimately had little effect. Since then, he’s been stopped and questioned several times by American customs officers.

“They did not seem impressed by the document,” said Roy.

Juneau-Katsuya said with the possibility of documents being falsified, there is a lot of “latitude” given to customs officers to decide how seriously to take them.

Roy’s fourth interrogation, in 2024, was a costly one. By the time American customs officials cleared his entry, he had already missed his flight to Tampa Bay and had to buy another ticket. And since he didn’t board his original flight, his return ticket was no longer valid and he had no choice but to buy a new one.

Air Canada initially refused to reimburse the $1,300 tickets, but reversed course after questions from La facture.

Databases aren’t as seen in Hollywood

With each interrogation, it takes time for officers to verify Roy’s identity.

Juneau-Katsuya says that, unlike in the movies, “we don’t necessarily have photographs associated with the databases that are checked by customs officers.”

He says photos are usually kept at the police station or at the place where the arrest was made.

Roy’s case is not an isolated one, according to experts consulted by Radio-Canada. Since the Sept. 11 attacks, the United States has greatly increased the number of names on its watchlist, said immigration lawyer Sarah Pelud.

The American border services turned down Radio-Canada’s interview request, but explained that the presentation of valid documents does not guarantee entry into the country. It said there are more than 60 categories that can deem a person inadmissible.

Fortunately, there is a little-known approach for those who suffer this type of mistaken identity: the Department of Homeland Security Traveler Redress Inquiry Program.

Those like Roy with repeated problems at the U.S. border can apply online.

Homeland Security can choose to provide the applicant with a redress control number that can be entered when booking a flight which certifies the person is not who they are often mistaken for at the border.

“Most of the time, when I take my clients through this process, we have favourable results. Unfortunately, there is no guarantee that it will be easier,” said Pelud, adding that U.S. customs officials have no obligation to inform travellers about this.

There is also the Nexus program to speed up border crossings between Canada and the United States. This is a pre-approval of low-risk travellers managed jointly by both countries.The Nexus card is valid for five years and it costs $120 to sign up.

But according to Pelud, if a person has had repeated problems at the border in the past, it is better to first obtain a number before applying for the Nexus program.

“The number helps clarify the traveller’s identity in control systems, which could improve their chances of acceptance into the Nexus program. In case of refusal, there is no appeal or refund,” she said.

Although Roy wishes he had known about the program sooner, he says it has made his last two border crossings go smoothly.