Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Sovereign bonds myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

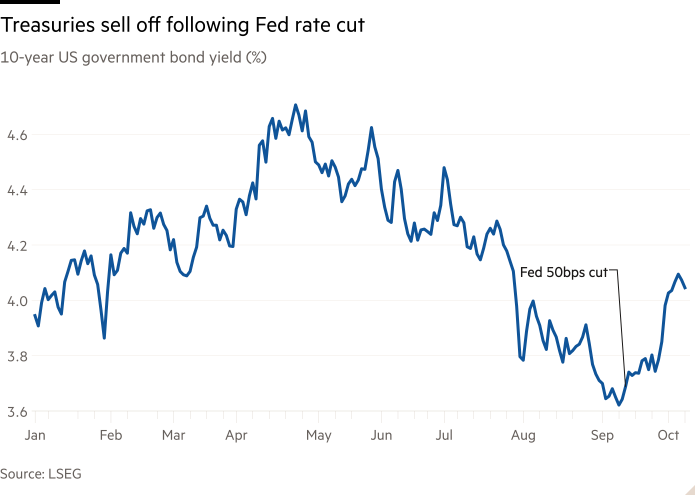

It increasingly looks like Jay Powell rang the bell at the top of the bond market. In mid-September, the US Federal Reserve that he chairs delivered two things that, on paper, should be good news for bonds: a supersized interest rate cut and a strong hint of more cuts to come. But this market, which underpins every other asset class on the planet, has sagged from that day on.

Yields on benchmark 10-year US government bonds have picked right back up to over 4 per cent — the flip side of sliding prices. About 40 per cent of the rally in 2024 has gone up in smoke, said Steven Major at HSBC, one of the big banks’ more keenly watched bond analysts.

“That was quite some move,” he said. “In the space of a few weeks, bonds gave back a significant proportion of the gains of the previous six months.”

This looks like a classic case of what traders call “buy the rumour, sell the fact”. Rate cuts were baked in to the bond market before they happened, and now the bet is stumbling, particularly with the later help of strong employment data.

In a sense this is good news. It means that in the recent divergence between rose-tinted stock markets and misery-loving bonds, stocks have won out. The cargo tribe of recessionistas will have to keep on waiting for their day to arrive after all.

The less good news is it suggests investors think the Fed gave inflation a free pass. “At the first signs that the economy might be slowing, central banks are in a rush to cut rates,” said John Butler, global head of macro at Wellington Management, a private investment firm with around $1.3tn in assets.

Powell was among those policymakers at pains to stress that, while the direction of travel on inflation was encouraging, it was not a case of “mission accomplished”. Instead, the balance of risks had tilted far enough that the Fed felt it prudent to cut rates hard to protect the labour market, which makes up the other half of its mandate. But the market is sending a more sceptical message.

“By cutting interest rates despite strong economic growth, the Fed now risks overstimulating demand and reviving inflation,” said bonds commentator Edward Yardeni in a recent note. “The bond market agrees with our assessment that the Fed turned abruptly too dovish recently.”

It is possibly still a little early to draw that conclusion. But to Butler at Wellington, it all suggests both monetary and fiscal policymakers are stuck in old ways of thinking.

“The market keeps oscillating when the ground underneath us is changing,” he said. China is no longer the great global disinflationary force it once was, and labour has more power to call the shots on wages and working conditions — a break from the past two decades or so.

This removes a “free lunch” from both fiscal and monetary policymakers, Butler said. In the past, governments could “ramp up debt with no implications”, confident in the assumption that global investors would continue to absorb their issuance. At the same time, central banks could keep borrowing costs low, believing the risk of an inflationary surge to be scant.

At a certain point, investors may balk at all the extra debt, and at the persistent threat of inflation, and demand a higher rate of return to stump up the funds. This perennial risk grows more pressing every time bonds dip in price for whatever reason.

The first big test of this will come from the UK Budget, in which chancellor Rachel Reeves will need to try to convince bond investors that she can borrow more within credible new guardrails. The scale of homegrown fiscal fears here is somewhat exaggerated by the gravitational pull of sliding US government bonds, but the nerves are real, particularly as we are only two years past the “mini”-Budget from Kwasi Kwarteng and Liz Truss that lit the kindling under UK debt.

“Gilts look cheap,” said Ben Lord, a bond fund manager at M&G Investments. “I want to buy them but we have got this risk, and it’s very close to the Kwarteng crisis to be doing this kind of thing.”

Similarly, the new downdraft in bond prices is awkwardly timed given that the US elections are just around the corner. It is a big “if”, but if we end up with an inflationary Republican sweep on top of an already hot-ish economy, then the argument that the Fed blinked too soon will grow louder.

It is now largely in the hands of politicians whether this bond market wobble turns in to something more serious. Any investors who do take fright are likely to find they are pushing on an open door.