This article is an on-site version of our Inside Politics newsletter. Subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every weekday. If you’re not a subscriber, you can still receive the newsletter free for 30 days

Good morning. Fast payments and leaps forward in connectivity have spawned a global stockpile of vulnerabilities that are ripe for nefarious exploitation, especially when policing lags behind. To put this in perspective: 40 per cent of UK crime is financial fraud, yet only 1 per cent of police staff are allocated to deal with it. In most cases victims in Britain can now claim reimbursement, but the under-policing and under-reporting of fraud remains a damaging obstacle.

Inside Politics is edited today by Danny Harding. Read the previous edition of the newsletter here. Please send gossip, thoughts and feedback to [email protected]

Foiled à deux

Say you see a nice wardrobe for sale on Facebook Marketplace (where you can even buy whole houses). You message the seller for their bank details, and you send over the sum. The item never turns up. Hurrah, you have just been defrauded. Purchase scams like this account for two-thirds of “authorised push payment” fraud. Those originating on Meta platforms including Facebook and Instagram dupe someone in the UK every seven minutes, Lloyds Banking Group estimates. Much of it is increasingly sophisticated — tricking people into payments using a plausible story, for example — and run by international and organised crime networks.

Fraud incurred short to medium-term socio-economic costs of about £16bn to 10mn victims in Britain between 2021 and 2023, according to Social Market Foundation analysis published last month. As Claer Barrett writes in the reader comments of her explainer, the psychological consequences are long-lasting, but harder to measure.

The UK does “relatively well” when comparing its fraud threat level internationally, the SMF found. But it is one of the first economies to make payment service providers (PSPs) refund fraud victims up to £85,000 in new rules that started last week (compensating victims was previously voluntary). It’s hoped that banks will increase counter-fraud measures if these payouts hit their balance sheet, with reimbursement costs split 50:50 between the bank that sends and the bank that receives the payment. One of them can levy a £100 excess charge when settling the fraud claim.

Will this work? Richard Hyde, co-author of the SMF report, says: “It’s an experiment worth running to see if you can erase some of the consumer detriment. We’ll see in a few years if it’s a net positive or net negative.” Industry lobby groups warned that fraud may increase, as criminals may stage fraud cases and abuse the framework. Some fear people will become less cautious.

PSPs can refuse reimbursement if they can prove the customer acted with gross negligence — one test of that is whether they ignore banks’ warnings — but this is a high bar and does not apply to customers deemed “vulnerable”. Vulnerability, as defined by the FCA in this hefty document, includes having “low knowledge of financial matters”. PSPs must also consider the extent to which the fraud victim was “in thrall” of scammers. So this stuff can get pretty grey. (This curious 2023 case of a defrauded couple who were conned by scammers and a fake Andrew Marr ad promoting cryptocurrency comes to mind. Under the “spell” of criminals, the couple lied to their banks and went ahead regardless, even after the latter warned they could be being scammed.) Working through masses of transactions and APP fraud cases to identify vulnerability may prove operationally tough, especially for smaller fintechs.

When John Asthana Gibson ironically became a victim of fraud while co-writing that SMF report, he noted another problem with the new reimbursement regime. His bank paid him back, so in his eyes, “a crime hasn’t really been committed”. With banks now mandated to refund victims within five days, there does seem to be little incentive for people to bother reporting it to local constabularies. (The obligations on PSPs to report to the police will depend on the particular facts of each case and the extent to which the consumer co-operates.)

Plus the reporting system doesn’t inject confidence. The Strategic Review of Policing found that in 2020-21 only 3 per cent of frauds reported to either Action Fraud, Cifas or UK Finance were assigned a police investigation and 0.6 per cent resulted in a charge or summons. The number of defendants prosecuted and sentenced for fraud offences in England and Wales plunged 77 per cent between 2010 and 2022. The maximum sentence of 10 years’ imprisonment (compared with 20 years in the US for comparable offences) for someone convicted under the Fraud Act 2006 is very rarely used. Even cases where the fraud involved is up to £100,000 would typically get four years, according to Stuart Miller Solicitors.

Investigating fraud is technical and labour-intensive — not to mention that an estimated 70 per cent of it has an international element, according to City of London Police — so you can see why the police calculus may fall not in favour of diverting stretched resources to root perpetrators out. Hyde found from his research that at least some of the public believe that, even if the police were able to trace the fraud operation, officers aren’t set up to tackle it. That then discourages reporting.

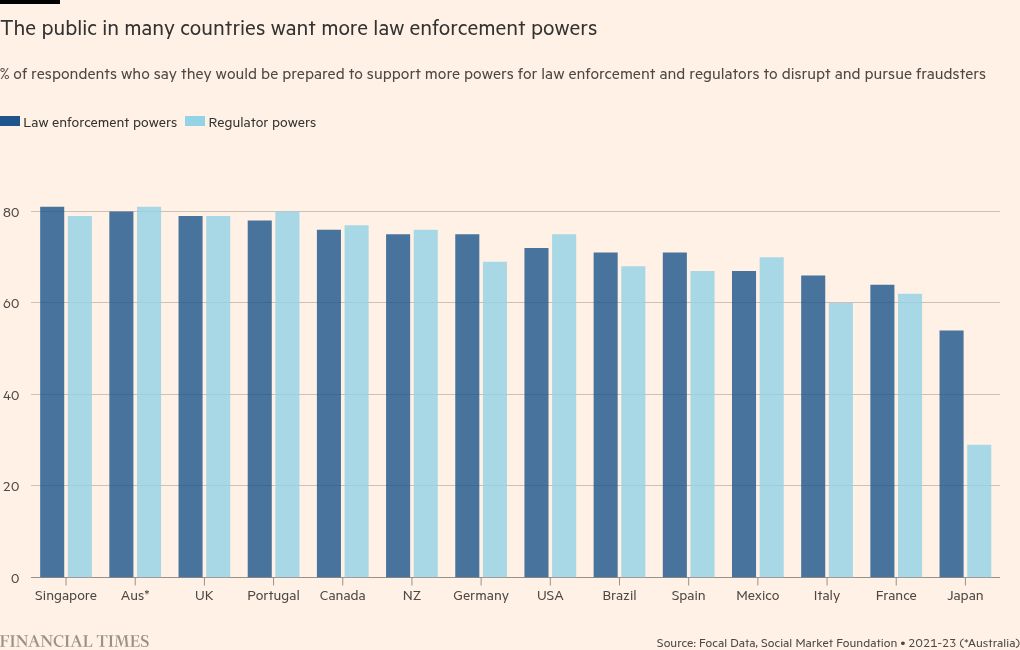

The SMF estimates that Britain needs 30,000 more specialist police officers and staff (eg digital forensic experts) to achieve a police force that is proportionate to the level of crime accounted for by fraud. Any progress depends on international co-operation. Data sharing between the public and private sector — for which there is wide public support, SMF polling shows — is also important, and has enabled a more co-ordinated approach in places like South Korea.

But legal experts I spoke to said sharing information across UK businesses to prevent fraud is complex. Piers Reynolds, partner at Freshfields, says: “There is a perception held by certain PSPs that there are barriers created by privacy and data sharing laws that create tensions with fraud prevention.”

We saw problems with connecting various agencies and banks together during the Covid loan scheme. As this write-up in the Institute for Government recounts: “Lack of fraud and error expertise made establishing the right data sharing with private banks more difficult.” Many other reasons hampered the rapid data sharing needed to identify fraud. Ministers accepted the high fraud risk (£4.9bn of fraudulent loans on a total of £47bn loaned in the Bounce Back scheme) because of speed. But the affair highlights the cultural, technical and capability barriers that must be overcome to disrupt criminals who are already benefiting from their sophisticated data networks. Laying the groundwork for similar sharing agreements is crucial.

Labour’s manifesto pledged it would introduce a “new expanded fraud strategy to tackle the full range of threats” and the party drafted plans before the election to make tech companies liable to fraud reimbursement. These suggest a serious reckoning, but many more levers need to be pulled and joined with international efforts. The reimbursement scheme is only one piece of the puzzle. Until the state beefs up a specialised law enforcement response, it will fall behind the swarm of criminals spanning the world.

Now try this

The Wolf and Owl podcast never fails to make me laugh out loud.

Top stories today

-

Labour’s pledge to slash red tape | Keir Starmer will ask Britain’s competition watchdog to soften its approach as he vows to “rip out bureaucracy” in order to make the UK a more attractive investment destination. He will unveil commitments from the private sector to invest more than £50bn into the economy — across AI, life sciences and infrastructure — according to people briefed on the plans.

-

Private finance’s patchy record on projects | Rachel Reeves is hoping to attract billions of pounds of private finance to upgrade the nation’s creaking infrastructure and will be courting potential investors at the government’s investment summit today.

-

Alex Salmond, 1954-2024 | Alex Salmond, who has died at the age of 69, was the central figure in the rise of modern Scottish nationalism, writes Mure Dickie in his obituary.

-

Cut the crop | British farmers are scaling back food production in favour of alternatives such as rewilding or growing crops for biofuels to keep their businesses viable, the president of the National Farmers Union has warned.

Recommended newsletters for you

US Election Countdown — Money and politics in the race for the White House. Sign up here

One Must-Read — Remarkable journalism you won’t want to miss. Sign up here