Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Myriam Mihindou was in her 20s, she suffered from aphasia, an inability to speak or understand speech. The French-Gabonese artist’s process of rehabilitation helped her find her voice, both literally and artistically, and she has since developed a multidisciplinary practice in which collaboration plays a central role.

This autumn, a trio of major French exhibitions — at the Palais de Tokyo, the Musée du Quai Branly and the Biennale de Lyon — are set to solidify Mihindou’s reputation as a key figure in contemporary French and African diaspora art. But it was in 2000, when she created her first video installation, that she first struck upon her current mode of working. “I became conscious that I was a performance artist,” she says from her studio in Vitry-sur-Seine, a south-eastern suburb of Paris, dressed in a T-shirt and yoga trousers.

This early video, “Folle” (“Mad Woman”), is part of the artist’s new retrospective at the Palais de Tokyo, the French capital’s foremost contemporary art space. Projected on to the floor of the gallery, it shows Mihindou’s feet from a first-person perspective. The viewer hears laughing and jeering as her toes nervously explore the crack between two paving stones. After much hesitation, the feet leap from one stone to the next and the laughing stops. It’s a simple but potent visual metaphor for overcoming one’s fears.

Born in 1964 in Libreville, Gabon, to a French Catholic mother and a Gabonese animist, political activist father, Minhindou recalls her childhood as a rich source of inspiration, but also one of terror. “My father was often arrested,” she says. “He spent 14 years in prison for defending his political ideas.”

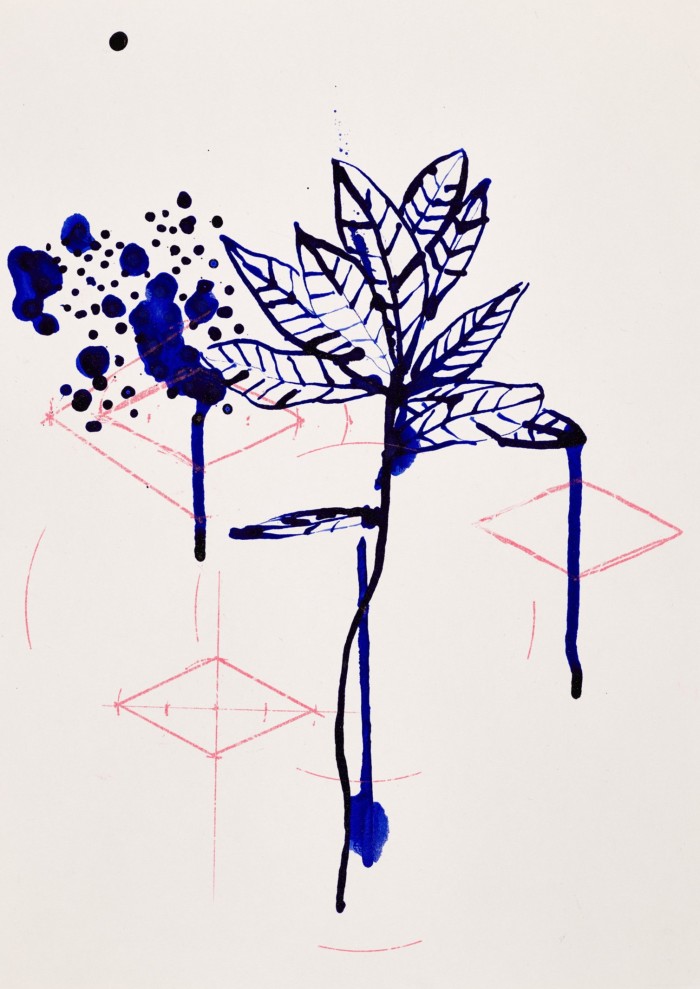

It was against the backdrop of her father’s opposition to the regime of President Omar Bongo Ondimba that Mihindou fled to France in the 1980s. In Bordeaux, she studied the architecture of the French colonial buildings that she had seen being razed. “When I was a child, the destruction of old colonial houses began,” she recalls. “In place of these houses, they built multistorey buildings, which drastically changed the atmosphere and the architectural memory of the neighbourhoods.” The destruction made her angry, she admits. “But I was able to separate the system from what that [same] system produced in terms of cultural heritage.”

Her studies did little to appease the pain of exile, however, and, to the dismay of her parents, Mihindou abandoned architecture to pursue a career in art. She enrolled in night courses at the University of Bordeaux, where a class on ruins provided the conceptual bridge between architecture and the internal conflicts that pressed her towards art-making. “I’m sort of obsessed with the idea of how to reconstitute the whole from a fragment,” she says. “Making things is, for me, a way of thinking through that.”

In 2004, Mihindou filmed “La Colonne Vide” (“The Empty Column”) in homage to her late sister. It shows a double image of the artist standing on a pedestal; as the figure on the right begins to move, walking backwards in a small circle, the one on the left follows with a few seconds of delay. Every so often, Mihindou stops to pose. She seems to represent herself and her sister as monuments of a very personal and individual kind. The subtle intertwining of personal story with political subtext is a recurring motif in her work.

It’s hard not to read these images against the context of ongoing debates regarding the presence of monuments to racist oppressors in public spaces. “I’m not an activist”, Mihindou insists at first, before conceding: “Alright. I am an activist when it comes to the question of pursuing certain goals. But I don’t like political structures. I don’t want to belong to a political movement or party.”

Themes of death and mourning are also present in her exhibition Ilimb, the Essence of Tears at Paris’s ethnographic Musée du Quai Branly. The show pays tribute to the Punu mourners of Gabon — an order of the ethnic group to which Mihindou belongs. In “Moñu” (2023), a long wickerwork braid snakes through the gallery; an embedded copper cord responds to the visitor’s touch, activating a sound recording of a Punu mourning ritual, guiding the souls of the deceased to the afterlife. Another work, “Nzumbili” (2023), presents what at first appear to be Gabonese wooden instruments, but which are actually trompe-l’oeil ceramic pieces. It both demonstrates Mihindou’s technical and conceptual sophistication and questions the museum’s conservation techniques and obsession with authenticity.

While these works dialogue closely with the concerns and contradictions of a colonial trophy museum, the installation “Lève le doigt quand tu parles” (“Raise your hand when you speak”, 2023-24), which was presented at the 2024 Biennale de Lyon, touches on broader social concerns. Impaled on a scaffolding of metal rods, cement casts of women’s arms point towards the sky in a gesture that speaks to the making invisible of women’s roles and highlights their demand to be heard.

When I ask Mihindou about this piece, she reorients the question, preferring to tell me about the collaborative process of making it. “At first, it was tough, laborious,” she recalls. “The poor crew, I think they were cursing me. After a while, each found their place. Then, each person started to deploy their intelligence, to push forward in their own capacities. We were constantly inventing. When you start inventing, it’s moments of laughter and joy. Depending on what’s invented, you really discover personalities, and that’s very beautiful.”

Palais de Tokyo, October 17-January 5, palaisdetokyo.com. Musée du Quai Branly, to November 10, quaibranly.fr; La Biennale de Lyon, to January 5, labiennaledelyon.com