Alex Kempshall planned his later life costs meticulously. Years before retiring from his job as an IT specialist, he calculated the income he would need to live comfortably, factoring in holidays and a paid-off mortgage. As soon as that goal was reached, he retired.

Then things started to unravel; within three years his financial plan was in tatters.

Kempshall, now aged 69, developed multiple sclerosis, with “no inkling” as to how quickly he would deteriorate, he says.

“I can now only get around using an electric wheelchair as I’ve lost the use of my legs. I’m starting to lose the use of my hands and arms,” he explains. “I use a knitting needle to press the keys on the keyboard. Eventually I won’t even be able to do this.”

He has two carers to help with washing, dressing and medication. His partner looks after him during the day, helping with mealtimes and transferring him from his wheelchair to the toilet. “Every so often it gets too much for us, so I go to a nursing home for respite care,” says Kempshall, who lives in Gloucestershire.

He pays about £1,800 per month for the carers, about 55 per cent of his monthly income: this comes from occupational pensions, state pension and disability benefits. “Eventually I will have to stay permanently in a care home, costing £84,000 a year.”

Kempshall is one of many FT readers who shared with us their experiences of accessing and paying for later-life care. Many struggle to discover what support is available and often face eye-watering and unexpected costs. But there are things people can do to put themselves in a stronger position should they or a loved one need care.

While Kempshall’s overheads might appear to be an outlier, experts in the field suggest they are anything but. Some calculate that care costs can soar to about £100,000 a year, while others pitch north of £200,000.

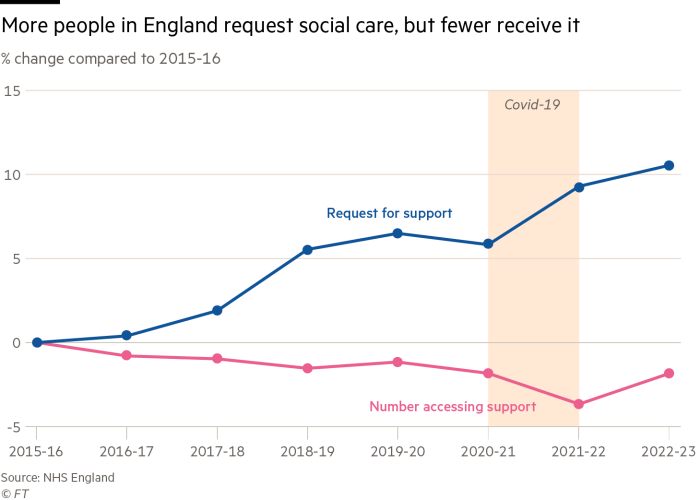

Access to care in England is means-tested, but ever-tighter local authority budgets mean a person must have significant care needs that make daily living tasks difficult, or few or no assets, in order to be eligible for state-funded support.

Those with more than £14,000 in assets are not entitled to free care; up to £23,250 and you might get some financial help “on a sliding scale”, says Caroline Abrahams, director of charity Age UK. In Scotland, care is free if a person is deemed eligible by their local authority, but Abrahams says this has led to “huge waiting lists” and an underfunded scheme.

Many people also wrongly assume care is “covered as part of NHS”, says Camille Oung, a fellow at the independent health think-tank Nuffield Trust.

The combined effect is that roughly two in five people are self-funded in a system where capacity is under severe strain and quality of care is patchy.

With around one in every three people likely to need care, an understaffed workforce, an ageing population and a lack of state funding, the outlook looks grim for those with few assets, and expensive for those with a healthier financial buffer. In both camps, experts say, scant attention is being given as to how care might erode their family’s wealth and, for some, fears around having to sell the family home have become a reality.

Plans for a cap on the amount a person pays towards their later-life care have been knocking around for more than a decade after a 2011 report by Sir Andrew Dilnot recommended a slate of reforms of the sector, but under successive governments action has been deferred.

It hit the buffers once again in July after Labour came into power. The proposed social care cap, most recently set at £86,000, was tabled to come into play from next October. The asset threshold for accessing state-funded care was also set to rise to £100,000. But after chancellor Rachel Reeves discovered the £22bn budget “black hole”, plans were postponed. The government has said it still plans to reform social care, but it remains unclear how and when any changes will be implemented.

Claire Macdonald, who is 71 years old and lives near Salisbury, Wiltshire, says it is a “scandal” that successive governments have failed to act, adding that the cap would have relieved anxiety over care costs and enabled people to plan.

Both her parents had dementia and needed expensive care, she says. “They would have been horrified if they were able to understand how much of their hard earned savings went on social care.”

Macdonald, who also campaigns for the introduction of voluntary euthanasia for mentally competent adults, adds that many old and very sick people are being kept alive against their will.

Age UK’s Abrahams says the message to individuals is clear: “You’re on your own . . . You’ve got to have enough money yourself, or in your family, and it’ll cost you a fortune.”

Landing on a ballpark figure is difficult when there are so many variables that could affect the cost of care, such as longevity, the care home or nursing home, medical needs and so on. Abrahams says people should look to initially set aside “a couple of hundred thousand at least”.

£72,000Annual residential costs in London, estimated by Which?

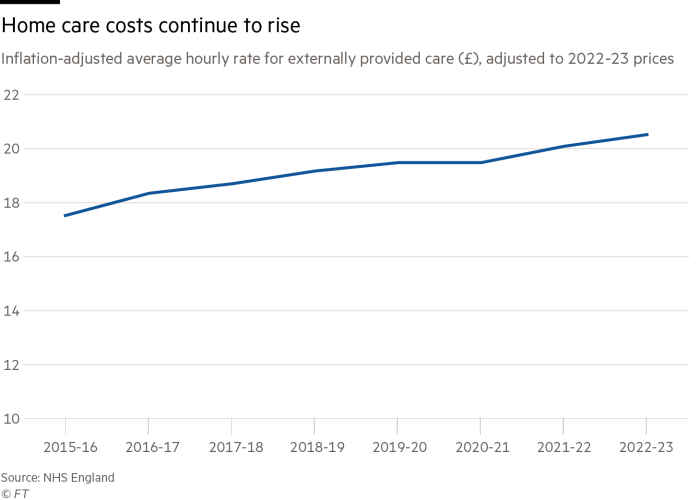

The type of care sought — a care home, a nursing home which is more costly, or domiciliary (at-home care) which can be more expensive still depending on the number of hours sought — is one such variable, says Tony Müdd, divisional director, development & technical consultancy at wealth management firm St James’s Place.

“But £1,500-£3,000 a week is not uncommon, meaning individuals could easily need £200,000-£250,000,” he says.

Location also feeds into costs. Recent data from Which? that shows Londoners could pay £1,383 a week (or around £72,000 a year) for residential care, which rises to £1,702 a week for nursing for dementia care. Round-the-clock at-home care could cost £180,000 a year.

In north-east England, nursing for dementia care would be lower at £1,099 a week (or £57,000 a year). “For luxury later-life care the costs are considerably more,” says Jenny Cutts, a private client lawyer at Wedlake Bell, who advises on wealth protection strategies.

Cutts says average life expectancy for care home residents in 2021-22 was around seven years for someone aged 65-69, and 2.9 years at age 90. So even for those who have put money aside, it’s easy to see how easily costs can spiral.

Kempshall’s case exemplifies how even the best laid plans can get knocked off course, making it all the more crucial that families try to plan. Such conversations are not always easy.

Liam, who did not wish to give his real name, is caring for his 87-year-old mother, who is beginning to suffer from dementia and ill-health. Carers visit for an hour three times a day, costing about £3,600 a month. She has “rapidly dwindling” savings of £30,000 and two homes, neither of which she wishes to sell.

Attempts to discuss the situation become emotionally charged, he says. “Trying to talk to her about money leads to panic, accusations of trying to run her life for her, or guilt and tears about not having sorted things out previously. So it gets shelved,” Liam explains, adding that the situation “weighs on the rest of the family’s mind”.

Devising a plan before an individual reaches crisis point is obviously beneficial, but this can come with its own dilemmas, too.

Ted Bower, another reader, and his wife — both in their late eighties — wish to use some of their wealth to help their son buy a property. But the possibility of going into care has left them feeling torn.

“Residential care seems to cost thousands a month while nursing care doubles up the cost, hence our dilemma and concern,” he says.

SJP’s Müdd says families are often reluctant to discuss financial matters but “really should”. He advises people to nominate a power of attorney, who can take control of their finances and wellbeing should they lose the capacity, and discuss how they wish to be cared for.

“Sadly families do argue about money between generations and between siblings,” Müdd says. “An open and honest conversation is the best way of trying to ensure this doesn’t happen.”

Care home costs can vary but higher charges and extra trappings in many privately run homes do not always translate into higher-quality care, some experts note.

Oung says the sector faces workforce shortages of about 131,000 at any time, with a heavy reliance on international hires. The appeal of care as a profession is hampered by the prevalence of zero-hour contracts and a lack of opportunity for career progression, she says. This has a knock-on effect on quality across the board.

A study this month by the Nuffield Foundation and Oxford university found public provision of adult social care has “virtually disappeared” with 96 per cent of residential services now outsourced to the private sector. This is despite inspections showing that privately run adult care homes consistently underperform their public and third-sector counterparts on measures of quality.

All the while, outsourcing to for-profit providers has accelerated, it adds, which has a negative impact on the wider system.

“Provisional findings suggest profit motivations are creating adverse pressures that are further destabilising and inequitably distributing already-strained care resources.”

The government has said it wants to “thoroughly review” the challenges facing what it has described as a “fundamentally broken system” before imposing reforms on the care sector.

“We are committed to tackling the significant challenges facing social care, and we will work closely with the sector and across government on our plans for effective reform,” the Department of Health and Social Care told the FT.

“As part of this, we are also committed to building a National Care Service — underpinned by national standards and delivered locally — to ensure that everyone can get the care they need.”

One of the biggest fears people flag when it comes to care costs is the idea of being forced to sell their home.

What individuals cannot do if it becomes apparent that care might be needed is to give away their home, or other assets, to shield them from inclusion on the financial assessment to determine eligibility for state-funded support. This is known as “deprivation of assets” and a local authority can still decide to include these in its calculations if it believes a person has done this deliberately.

However, Age UK’s Abrahams points out that “there’s no reason why someone has to sell their home during their lifetime” as people can make a “deferred payment”, in effect a loan from the local authority that means a person will not need to sell their home to pay for care until their death. In England and Wales, a local authority may charge interest on the loan; in Scotland there is no interest charged while the agreement is active. In 2022-23, 2,370 new DPAs were agreed, according to NHS data.

A home’s value may still nevertheless form part of how many people will choose to pay for their care.

One reader, Ian Kennedy, a single 84-year-old, would like to leave some assets to his younger relatives, but accepts he might need residential care in future, for which he may need to use his flat to pay for the costs.

“I have difficulty in understanding why people cannot accept that the property they own may have to be sold to finance their care,” he says. “Somebody has to pay for care for the elderly and, in my view, it should be property owners.”

It is difficult to provide affordable insurance products where there is no cap on the liability, says Jamie Jenkins, director of policy & communications at Royal London, an insurer. So previous iterations of long-term care products became “unviable”.

But there are some specialist products available. Some newer equity release products, for instance, enable people to release value from their home “but with family members paying the interest incurred” to limit the impact on the estate for inheritance purposes, Jenkins says. He urges people to take financial advice.

Lorna Shah, managing director of retail retirement at insurer Legal & General, says some of its customers use a lifetime mortgage, “a type of equity release secured against the home, which doesn’t have to be repaid until the last surviving borrower dies or moves permanently into a care home”. Funds released in this way can be used to pay for care without having to move out of that home, she says. The downside is having less equity to pass on to relatives on death.

There is also a “care fee annuity” or “immediate needs annuity”, says SJP’s Müdd. The individual pays a relatively large upfront lump-sum payment, which provides an income for life and is paid tax free if the payments are made to the recipient’s carer. (2plan Wealth Management has an immediate needs annuity calculator here.)

Beyond insurance products, Müdd says individuals should prioritise accumulating assets in the most tax-efficient way and that suits their investment risk profile. “So pensions, Isa, high interest bank accounts, unit trusts and so on. There is no magic bullet solution.”