This is the little that Gilad Korngold knows about what happened to his son on October 7. He knows that Tal, the 39-year-old father of Yahel and Nave, and husband to Adi, was taken from Kibbutz Be’eri by Hamas. That he was thankfully uninjured, that he was clothed, that he was stuffed into the boot of a car, and that he then vanished into the hell that is the fate of an Israeli hostage in Gaza.

He believes Tal is alive, or at least tells himself that he must believe Tal is alive. He also knows from other hostages that they sometimes were allowed to listen to Israeli radio, or saw their families on Al Jazeera, the Qatari news channel omnipresent across the Arab world.

And so, Korngold, 62 and struggling to remain strong, never misses a chance to appear on the radio. Perhaps, he hopes, the airwaves will carry his voice the 15km or so across the border with Gaza, and let Tal know his family hasn’t abandoned him, even if he believes the Israeli government and the world have done so.

He tells his son, “We love him, that if you hear us, know that your family is being protected,” he says. “I need [you] to be strong, because we are almost there.”

But it’s been a full year since October 7 and “we are not there”. Tal’s wife and children, then 8 and 3, were released in November, during a single round of Israeli-hostage-for-Palestinian prisoner swaps. But their father remains in Gaza.

Much of Korngold’s anger is directed against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, whose government is “doing everything so that the hostages issue will be forgotten”, Korngold insists. “He doesn’t care about the hostages.”

But he is also uncomprehending about what he says is the lack of international attention. The International Committee of the Red Cross brings no news of the hostages, he complains, yet protests over the conditions Palestinian prisoners are held in, in Israel. The Europeans send aid to Gaza, but do little even for those two dozen or more Israeli hostages with EU passports, he says. The Americans have the power to force Hamas and Netanyahu into negotiations and say “‘Don’t eat, don’t sleep, don’t breathe, don’t drink until [there is a deal]’, but it looks like they have their own [timeline].”

Even the plight of Kfir and Ariel Bibas — who turned 1 and 5 while still in Hamas captivity, their red hair and blue eyes ubiquitous around Israel on “Bring Them Home” posters — seems unable to rouse the Israeli government or the world. “How come that nobody cares?,” Korngold asks. “Not in this country. Not in the United States. Not in Europe.”

“No one is talking about this. The world has football, the World Cup, now next month probably the Winter Olympics or something,” he says. “The world has gone crazy.”

For many Israelis, the world truly has gone crazy. They understand, almost instinctively, that on the larger intractable issues of Israel’s place in the Middle East and on the question of a Palestinian state, they are on the wrong side of international public opinion.

But when it comes to the plight of their hostages — frail old men and innocent little children, young women facing the threat of sexual assault and civilian fathers held as military-age prisoners of war — it is incomprehensible to them how little the world seems to care.

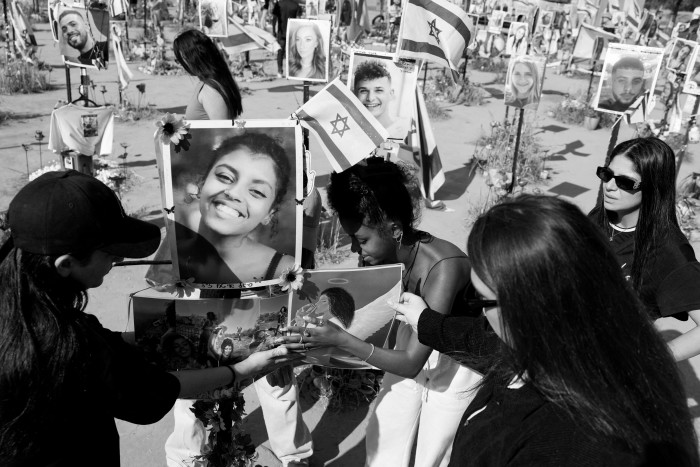

It is now a year since October 7, when Hamas militants burst into Israel’s southern kibbutzim, outwitting the Israeli military and rampaging through the small, often isolated, outposts of Zionist utopias, terrorising the Jewish state.

Over that year, Israelis have seen an initial outpouring of compassion gradually curdle into censure and condemnation, especially as the death toll and suffering of Palestinian civilians in Gaza became apparent.

“There was a catastrophe here, one of the most heinous days in world history where Israelis went through things that would make the Nazis pale,” says Udi Goren, whose cousin was among the 1,200 people Israeli officials say were killed on October 7, his corpse still held by Hamas. “That was one day, how the war began, but after day one, all you hear is ‘the Gazans are suffering’.”

“What I would least want to do is have a contest of who’s suffering more,” he says. “Neither Gaza’s civilians should be suffering so much nor should we — but when you have this story that seems like a David and Goliath, it’s very, very easy to overlook the devastation and the price that we are paying.”

Israel’s war on Hamas has killed almost 42,000 people, mostly women and children, Gaza health officials say, a thunderous offensive that has devastated the besieged enclave. Its 2.3mn people are nearly all displaced, most of their homes destroyed, forced to live and care for their children in a rubble-strewn, uninhabitable wasteland. Disease is rampant, famine at their doors.

The condemnation of the Israel Defense Forces’ actions in Gaza — even from their closest allies — has turned Israelis inward. Despite the steadfast support of the US, and many western governments, Israelis today say they feel abandoned by the world, painted as callous to Palestinian suffering when they are overwhelmingly convinced that they are acting in self-defence, prosecuting a just war against an enemy that hides behind civilians.

“Do you know why I hate Hamas?” says Hai Bar-El, a human rights lawyer based in Tel Aviv. “I hate Hamas because it forces my children to kill Palestinian children.”

How Israelis feel matters not just as a question of empathy but because it is shaping the military campaigns that Israel is now waging across the region. The embattled mentality that has taken hold over Israeli society, blending victimhood with resentment, has resulted in overwhelming support for the relentless onslaught in Gaza.

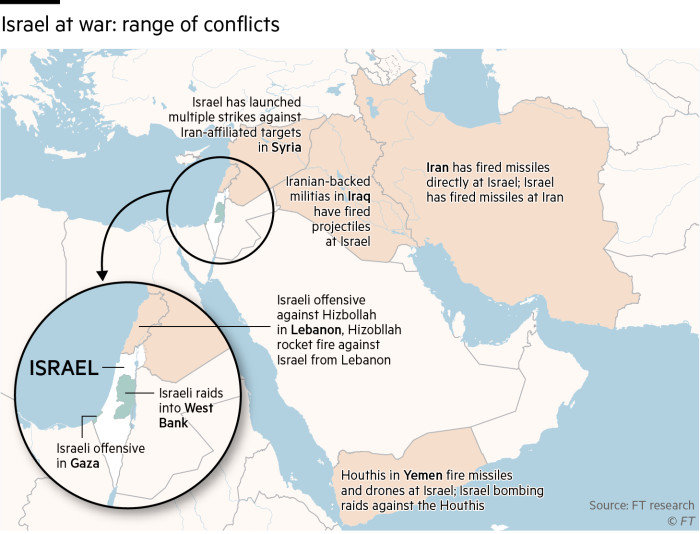

Even before it winds down its war in Gaza, where both a clear victory and the return of the hostages remain elusive, Netanyahu has turned the full might of the IDF to Israel’s northern border, against the Lebanese militant movement, Hizbollah.

That conflict, which has simmered alongside the raging battles in Gaza, started when Hizbollah fired rockets into Israel the day after October 7, reinforcing a latent fear that the country is facing an existential threat from Iran and its proxies.

Over the past two weeks, Israel has killed Hizbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah and many of his top commanders, while launching waves of air strikes on Lebanon and a ground offensive into the south of the country. Israeli bombs have killed more than 1,000 Lebanese in the past two weeks and forced more than 1mn from their homes.

Rooftop bars in Tel Aviv saw an outburst of joy over last Friday’s assassination of Nasrallah, who was as reviled as he was dreaded in Israel. He was killed in a bunker deep under the ground after dozens of bombs demolished six residential blocks in Beirut — the pilot bragging about Israel’s ability to reach “everyone, everywhere”.

Netanyahu is conducting this campaign with the country’s support, locking it into the longest period of war in its 75-year history, his far-right government channelling a shared national rage into more wars. He denounces allies who dare call for “de-escalation”, promising Israelis that he will defy global pressure to continue pursuing Israel’s war goals — “total victory” against Hamas and the degradation and defeat of Hizbollah — while issuing warnings to Iran that “there is no place” in the Middle East that “the long arm of Israel cannot reach”.

The world is waiting anxiously for his response to Iran’s missile attack on Israel last week, concerned it will ignite the all-out war the region has long feared.

“We had this reputation that we were a weak society, that we were not determined, not willing to go all the way,” says Micah Goodman, a philosopher and prominent Israeli intellectual, referring to speeches by Nasrallah and Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. “Israelis want to repair that reputation, and come to a point where the west understands us, but the Middle East fears us — that’s when Israelis will finally feel safe.”

Nowhere is this chasm between how Israelis see themselves and how the world sees them more apparent than in the toll the war in Gaza has taken on civilians. Earlier this year, 94 per cent of Israeli Jews believed that their military was using either the appropriate amount or too little force in Gaza.

When they turn on their televisions, Israelis see little, if anything, of the devastation in Gaza, the plight of Palestinians being attacked and forced off their land by Jewish settlers in the occupied West Bank, or the destruction in Lebanon. Instead, because much of the mainstream media has marched to the drumbeat of war, Israeli news mainly concentrates on Israeli military operations and the plight of the hostages.

If Israelis ask why international anger about the IDF’s conduct outweighs sympathy for their pain over October 7, for many the response is that it is an open and shut case of antisemitism. Ehud Olmert, a former Israeli prime minister, acknowledges that anti-semitism is on the rise, but he believes that often the more innocent explanation is human nature, a natural sympathy for the underdog.

“You turn on the TV, and you see 1.5mn Palestinians, walking through the ruins of Gaza with their plastic bags, looking for a place to sleep, for something to eat,” he says. “At that moment, you don’t want to see the 1,200 Israelis killed [on October 7], the 70,000 people displaced.

“They know the Israelis have a government that will take care of them, a government that they maybe think is committing war crimes against the Palestinians,” he continues. “This perception may not be fair, may not be honest, may not be accurate, but this is very hard to combat.”

Goodman, the Israeli intellectual, argues that Israeli suffering should not be minimised just because the country happens to be more powerful. “That is the feeling of being Israeli today — you feel radically misunderstood, you feel like you’re not being seen,” he says. “Israelis see how hostile people are on the streets of Europe, and among the academic elites in America — but do [these people] see that Israel is a country that’s in a war and fighting for its existence?”

Israel, he says, is trapped between its desire to be accepted by the west — mainly the US — while trying to survive in the Middle East, surrounded by lethal enemies. “Trying to keep high levels of legitimacy also erodes our deterrence, because we’ll avoid doing things that need to be done because you don’t want to lose the support of America,” he says.

That tension is exacerbated by the fact that many Israelis feel the current threat from Iran represents the greatest peril the country has faced since the 1973 Yom Kippur war.

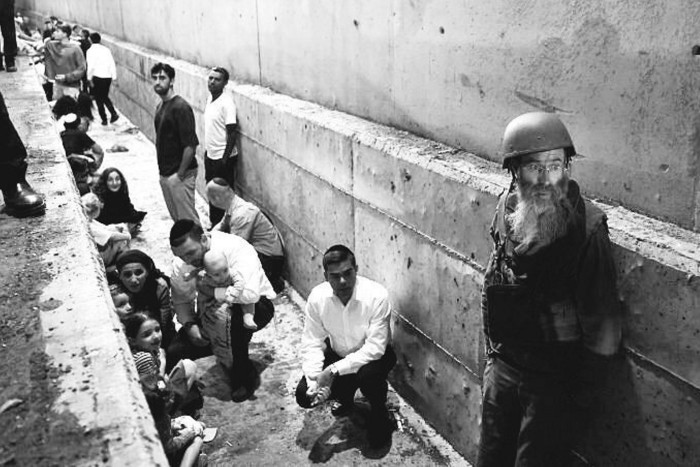

Lior, a retired police officer who retrained to be a therapist, says versions of this fear now seem endemic in her 30 or so patients — the idea that they may one day be forced to choose between their homes and their safety. She asked not to be identified by her last name because discussing her patient’s confessions, even in the aggregate, could put her medical licence at risk.

One of her patients spent the first few days after the Hamas assault locked in her safe-room, downloading dozens, if not hundreds, of the videos that the militants and witnesses to the massacres uploaded to the internet. She now carries a licensed firearm, keeps her car fuelled at all times and is considering getting a large guard dog, even though she lives in central Israel — far from any possible cross-border raid.

“The entire country is experiencing a shared trauma,” Lior says. “Ask your [Israeli] friends how safe they feel, and count the caveats in their answer.”

Within Israel, the fate of the hostages has become perhaps the most divisive issue in the war, says Sharone Lifschitz, the daughter of 86-year-old Yocheved and Oded, 85, both taken hostage from their homes in Kibbutz Nir Oz.

A significant majority of Israelis want Netanyahu to accept a US-backed deal that could see them released in exchange for a ceasefire with Hamas and the release of Palestinian prisoners. Netanyahu has refused, saying it would leave Hamas intact.

Yocheved electrified the nation with an impromptu and unfiltered press conference the day of her release, just 16 days after being taken captive, but divided opinion with the handshake she offered to a masked Hamas militant at the moment she was being handed over to the International Committee of the Red Cross. Her husband, frail and elderly, remains in captivity, and it isn’t clear if he is still alive.

Now, Sharone says, the fate of her father and the other hostages has become so politicised that they are sometimes seen as the reason why Israel can’t achieve the “total victory” that Netanyahu keeps promising the country. The families of the hostages overwhelmingly favour a ceasefire, arguing that the political and military cost of that truce is Netanyahu’s and the army’s responsibility for their failures on October 7. Netanyahu’s far-right coalition allies describe that as surrender, and have threatened to bring down his government if he agrees.

“Now you have people whose children are soldiers in Gaza and they are thinking their children cannot fight freely because of the hostages,” Sharone says. She worries that in the “bottom of their heart, they just wish the hostages were not there any more”.

In many ways, she wonders if the sympathy from non-Israelis for her father, so frail and in captivity for so long, is tempered by people’s opinions of Israel itself. “It’s a complicated [issue] — people conflate the hostages with the government,” she says. “Israel in the world is a bit like the hostages — a lot of people would just rather wish it wasn’t there.”

Korngold, Tal’s father, says that while they await a possible deal over the hostages, he knows he “must keep the family afloat”. They are not only dealing with the continued absence of his son: three members of the extended family were also killed on October 7 in the kibbutz.

Korngold’s grandchildren are still haunted by memories from their captivity where they were held for 50 days with little food, guarded by armed men, and forbidden to speak, lest their Hebrew give them away as Israeli captives to collaborators who could have sold their location to the Israeli army.

“The children saw everything that happened,” he says — including the dead bodies of neighbours and friends. “The situation is actually very bad now, worse than at the beginning . . . They talk about their father. They know exactly where he is.”

Without him, says Korngold, “it’s very difficult to help them to recover.”