Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In this newspaper we spotlight the work of the rich and powerful. Business and political news dominates. We forget, usually, that this world of shiny workplaces and frictionless lifestyles is made possible by the unseen, underpaid work of millions of office cleaners, refuse collectors, domestic staff — and sex workers.

Hard Graft: Work, Health and Rights, at London’s Wellcome Collection, puts a long overdue spotlight on these forms of physical labour. The space is divided into three zones headed “The Plantation”, “The Street” and “The Home”. These sections reflect locations of physical labour, starting with enslavement on plantations, and their legacy today; passing through the street — traditional site of sex work and refuse collection — and finally into the home, where domestic workers may be trapped in modern slavery. Each of the three areas is bounded by latticed timber walls, generating an impression of inside/outside spaces, enclosure and freedom.

The exhibition brings together unexpected combinations of art and artefact to make new connections in the viewer’s mind about power, resistance, racialised oppression — and the effects of hard labour on individuals. Items in the show span the early 19th century to the present, from a slide rule (1823) used to calculate treadmill productivity in prisons, to a new multimedia installation by Moi Tran, “Care Chains, Love Will Continue to Resonate”, made with the participation of 12 domestic workers in the UK.

These connections are subtle — nothing is forced upon the visitor. The inclusion of many of the objects is anyway self-evident (late 19th-century photographs of night-soil workers in China; thumbnail portraits of early 19th-century prostitutes with their names and charging rates). And there’s a big name among the emerging art talent: a series of nine pictures (of tools) by Turner Prize winner Lubaina Himid, subject of a Tate Modern retrospective in 2021/2022.

There’s hope here, as well as anger and misery. One of the show’s strands follows the long history of collective action in response to exploitative employers, as well as spotlighting the physical and spiritual healing practices shared among enslaved and marginalised communities.

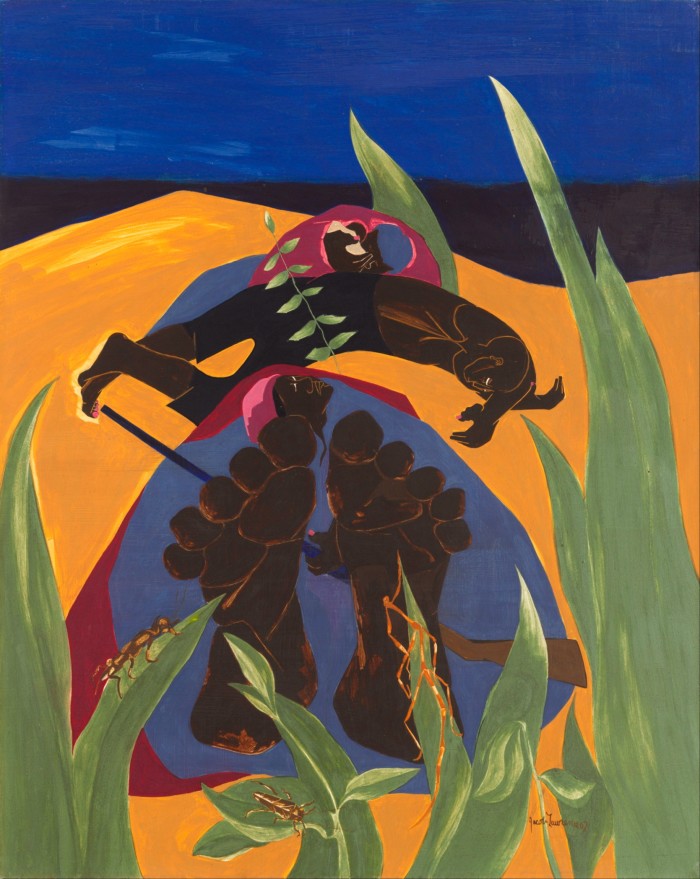

Reflections of resistance that caught my attention included a range of 1970s “wages for housework” campaign badges and a joyful 1967 painting, “Daybreak — A Time to Rest”, by the African American artist Jacob Lawrence. (This piece is on loan from the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, and in the UK for the first time.) I loved a wall of portraits by Charmaine Watkiss, a Black British artist interested in the herbal healing traditions of Caribbean women. The show links Watkiss’s work back to the medical knowledge that enslaved women shared, pairing the exhibit with a book by the pioneering 17th-century German-born botanical artist Maria Sibylla Merian. Going further, we learn that while researching in Dutch Guiana, as the objects catalogue points out, “[Merian] had direct contact with enslaved workers . . . her writing and social status were complicit and benefited from slavery.”

The centrepiece (and for me, the highlight) of the exhibition is a site-specific commission: a room-filling model of a church. Closer inspection reveals that it’s two different churches. The interior of Lindsey Mendick’s “Money Makes the World Go Round” installation represents the Saint-Nizier church in Lyon and the Holy Cross church in St Pancras, London. Both were occupied by sex workers in landmark protests — in 1975 in France and 1982 in London. It’s playing with our notions of churches as sanctuary and safe spaces. I had no idea about this hidden history of resistance. Mendick collaborated with members of SWARM (Sex Workers Advocacy and Resistance Movement), a sex workers’ collective, in making it.

Around the front, inside the church, there are rows and rows of ceramics — for example, a yellow danger sign of the sort used to warn of water spillage instead reads: “Danger: Death by strangulation is an occupational hazard”. One could spend a long time here, examining each ceramic and listening to the “sermon” by the writer Mendez, author of the novel Rainbow Milk, about their past experiences as a sex worker.

The “graft” in the title of the show will mean “work or physical labour” to a British visitor. But “graft” in American English has evolved into something darker. The Columbia Journalism Review points out that: “Around 1865, the OED says, ‘graft’ in the US was ‘The obtaining of profit or advantage by dishonest or shady means’.” Much of Hard Graft could also fall under a US meaning of the word. Many abuses of power are depicted here. One of the most simple and effective is a display of architectural floor plans from South American villas. Daniela Ortiz shows how tiny the maids’ rooms are — little more than cupboards — when shown alongside the owners’ vast living spaces.

Everything in this exhibition is far removed from “bullshit jobs”, as coined by the late David Graeber. These, broadly, are desk jobs where knowledge workers fill hours with the emails and instant messaging that, along with neverending meetings, make up the displacement activity done in lieu of meaningful work. Many of the contemporary workers depicted in Hard Graft make a difference in ways that most of us will never do.

I’ve no wish to undermine the seriousness of mental health conditions that affect far too many workers of all types, but this exhibition also reminds those of us who work behind desks that the toll of physical labour is paid with the body. It’s a reality embodied in “Washerwoman” (2018) by Shannon Alonzo. A woman is slumped, headless, over a tin bath of washing. Her dress is made from clothes pegs and her hands and feet are gnarled and calloused — it’s almost painful to look.

On leaving the building, I reflected that I was five minutes’ walk from the thriving primary school where I serve on the governing body. Many of its pupils have parents working hard to survive on very low incomes in the centre of one of the most expensive cities on earth. The reality of hard labour deserves, and receives here, honour — and long overdue recognition.

To April 27, 2025, wellcomecollection.org

Isabel Berwick hosts the FT’s ‘Working It’ podcast and writes a weekly newsletter about the workplace and leadership. She is author of ‘The Future-Proof Career’