Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is the FT’s architecture and design critic

This week the UK lost its last coal-fired power station and almost its last blast furnace. Or rather, we still know where they are — Port Talbot and Ratcliffe-on-Soar — but they have stopped working (the last working blast furnace, in Scunthorpe, also faces imminent closure). The physical infrastructure remains very much present. But it will almost certainly all be demolished in what seems an incredible disregard of an archaeology of carbon that will one day look unimaginable.

The nation’s industrial landscape has suffered astonishing contempt. The Teesworks site in Redcar, billed as the UK’s biggest regeneration, was flattened in 2022. Nothing of its epic landscape of steel production was preserved; instead an anonymous and undistinguished arrangement of tin sheds is proposed. Next year will see the closure of the Grangemouth oil refinery, Scotland’s last; another site that cannot help but stimulate the visual senses will soon go dark.

This architecture of carbon and concrete, of steel and impossibly complex tangles of ducts and pipes, illuminated and belching steam and smoke, has the capacity to be simultaneously hellish and exciting. And, most important, it is already there. By this I mean that we may never be building on this scale again. Our new infrastructure of distribution centres and the like is made deliberately anonymous.

At the same time there is much talk of neglected places and left-behind communities. In the first wave of deindustrialisation in the Thatcher-era there was a sense, perhaps, of shame, of deliberately destroying the landscapes of coal, steel and ceramics, as if their absence would aid forgetting. But those places remained left behind. Perhaps if the infrastructures of power and production had been in part preserved, that sense of identity and belonging, of some respect for heritage and generations of hard work, might not have seemed so heartlessly neglected.

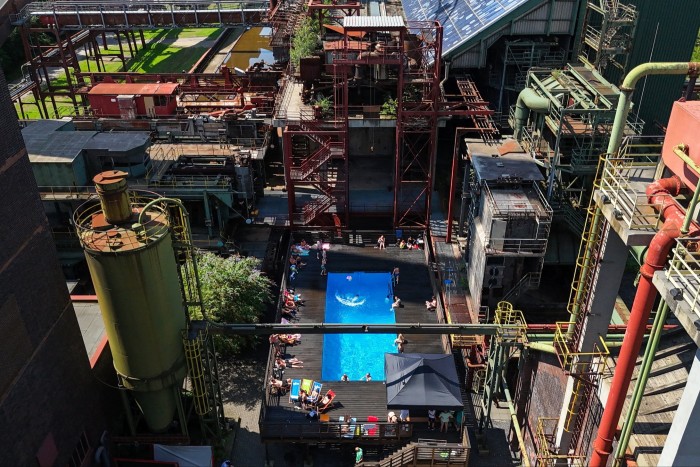

Where industrial buildings have been preserved they have proved hugely adaptable and popular. Think of Tate Modern in London with its Turbine Hall, converted from a vast power station and arguably London’s greatest new public space. Or Battersea Power Station — now with a hotel, residential and office blocks and retail space — or the Centre for Contemporary Art at the Baltic mills in Gateshead.

Nowhere has done it quite as extensively as Germany’s Ruhr valley with its vast legacy of rusting towers and ruined foundries turned into mesmerising follies in public parkland. The remarkable Inota outside Budapest (for which the familiar cooling-tower shapes were invented in the 1950s) has shown how cavernous industrial interiors can lend themselves to booming club nights and shows with incredible acoustics. Meanwhile, a pair of cooling towers in South Africa’s Soweto Township have been successfully repurposed as a venue for extreme sports.

Back in the UK, the Twentieth Century Society, which lobbies for the protection of modern buildings, has a campaign to save the nation’s cooling towers, like the dense huddle at Ratcliffe, gone quiet this week. In the 1960s there were 240 of these huge concrete towers, like pots in the process of being thrown, across the country. Now there are 45 left and those are mostly earmarked for demolition within the decade.

These places are cathedrals of power, looming, ready for reimagining. The reason Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall is so impressive is that we could never now justify building on that scale for culture today. Yet these places exist and they could provide epic centrepieces and markers for the much-touted new towns. One such at Fawley in Hampshire saw the demolition of a power station with its glam-futuristic 1970s control room, only for the town site to be abandoned as depressingly bleak.

These powerful structures have consistently inspired culture. German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher’s portraits of industrial structures founded a new movement in objective photography — the Düsseldorf School, from whence came Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer and Thomas Struth. Playwright James Graham broadcast a plea on the BBC to save the Ratcliffe cooling towers, familiar to him from his childhood. And director Ridley Scott, in creating one of the most memorable futurescapes in the film Blade Runner, attempted to evoke his memories of the now flattened Teesside steelworks at night, belching smoke and spitting fire like monstrous metal beasts.

The buildings might be at the end of one of their lives — they represent a carbon catastrophe and a planetary crisis, after all — but all that embodied concrete, energy, architecture and hard labour could be better served by maintaining them as relics from a past that will, one day, be almost incomprehensible. For the nation that pioneered the industrial revolution to be so careless with its industrial sublime looks intensely short-sighted.