Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

What immediately strikes you about Seoul, the South Korean capital, is its energetic mix of traditional and modern. It’s there in the architecture — the ancient wooden city gates against the steel and glass of high-rise office blocks — and it is also vibrantly represented in Korea’s traditional music, which is currently undergoing a revival in new contemporary forms.

These sounds can be heard in London’s annual K-Music Festival, opening this week; the festival has been running since 2013 with the soft power support of South Korea’s Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism.

The headline event is the visit of the National Changgeuk Company of Korea with a version of King Lear. Changgeuk is itself a mix of ancient Korean and “modern” western theatre traditions that was created a little over a century ago.

Korea’s traditional dramatic genre is pansori. It’s just one singer, narrating and playing the parts, accompanied by a drum, telling a long narrative story in a harsh and growly singing style — captivating, but an acquired taste. Changgeuk takes its music from pansori, but the narrative is given to individual characters and the instrumental accompaniment is expanded. It becomes something like theatre as it is known in the west. The NCCK have done changgeuk versions of the pansori canon, but also versions of western classics such as Euripides’ Trojan Women, which was highly praised when it toured last year in Europe. King Lear premiered in Seoul in 2022 and, according to composer Han Seung-seok, “the audience were very surprised how iconic western drama blended so well with the pansori tradition.”

Han sang with the NCCK from 1998-2002 and has been involved on the production side since 2014. He sees changgeuk as much more accessible than pansori. “Young people in Korea don’t necessarily grow up encountering traditional music, so find pansori very difficult to appreciate. In changgeuk, as in western theatre traditions, we have many different characters in their own costumes with props, set design, lights and theatrical devices, so it’s easier for the audience to engage in the narrative and drama.”

While the key music is composed by Han, there’s incidental music for piano and western instruments composed by Jung Jae-il, who wrote the soundtracks for the multi-Oscar-winning film Parasite and Netflix series Squid Game, adding a more contemporary edge.

Perhaps most intriguing is the casting of Lear. The aged king, dividing up his kingdom at the end of his life, is played by Kim Jun-su, an actor in his thirties. “If this had been a straightforward piece of drama we couldn’t have cast him,” says Han. “But as a pansori singer Jun-su has played many different roles of all ages — even animals, in the Sugungga pansori [about a tortoise and a hare]. So he has been well trained to express many different characters’ psychology and emotions.”

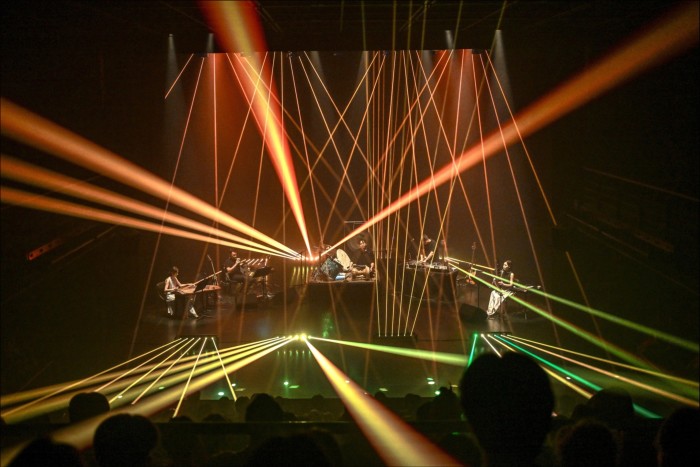

Far from the slick, ultra-processed offerings of K-pop, the K-Music Festival also offers an introduction to bands deeply rooted in Korean tradition, who have found enthusiastic audiences in the UK, Europe and the US. The most successful band in the Korean new wave is Jambinai, who fuse traditional sounds with heavy metal influences, combining haegeum (two-string fiddle) and geomungo zither with electric guitar, bass guitar and drums. Jambinai are not performing this year, but their leader Lee Il-woo is coming with his other, more traditional band No-Noise, which features six musicians on daegeum (flute), saenghwang (mouth organ), piri (flute), gayageum zither, guitar and synthesiser. If their name suggests a quiet evening, Lee’s involvement ensures that’s not the case. One of their pieces aims to create the impression of the mayhem of a busy town square, with different voices converging.

Korea has three types of zither which figure prominently in its traditional music. The most common is the plucked gayageum, with an elegant and refined sound. Much more harsh is the scratchy bowed ajaeng, which is largely heard in classical sanjo recitals. But most funky is the geomungo, plucked and rhythmically strummed with a bamboo stick. This is why it has a central role in Black String, another high-profile group performing at the festival. Drawing on jazz for inspiration, the four players brilliantly interweave their lines against virtuoso traditional drumming, a Korean speciality.

Black String’s leader Youn Jeong Heo was attracted to the geomungo at an early age. “Except for percussion, it’s the most rhythmic of Korean traditional instruments,” she says. “Traditionally it’s known for gentle and meditative sounds and I wanted to completely transform it and make it work like the guitar in a rock band. It’s that multi-dimensional sound that appeals to me as a musician.”

They’ll be premiering Road of Oasis, their third album, influenced by the ancient desert Silk Road and its music. “Black String was really born in London, thanks to a collaboration with saxophonist Tim Garland in the London Jazz Festival,” Heo says. “We Korean musicians grew into Black String. UK audiences were an inspiration, they give me so much energy.”

Changgeuk ‘Lear’ is at the Barbican, October 3-6; Black String are at Kings Place, October 31; No-Noise are at the Purcell Room, November 15, kccuk.org.uk