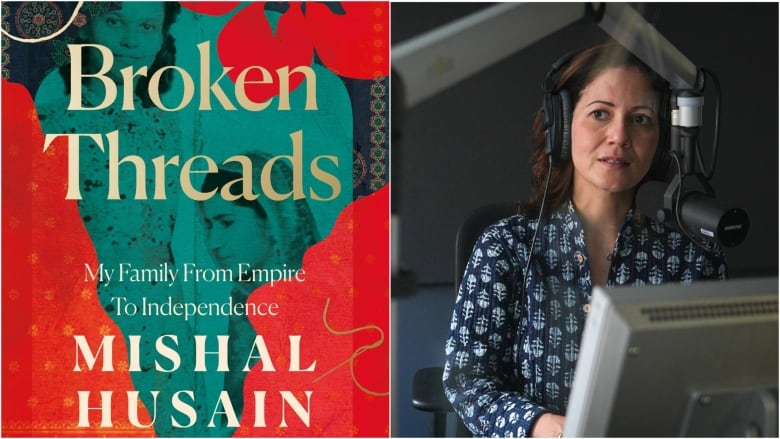

As It Happens26:49How the Partition of India shaped BBC host Mishal Husain’s family history, and sense of self

In her new book, BBC journalist Mishal Husain tells the story of her own family. But in doing so, she says she’s telling “the story of many families.”

Husain, host of BBC Radio’s Today and BBC TV’s News at Ten, was born and raised in England to Pakistani parents. But just one generation before that, most of her relatives were not citizens of any country, but rather subjects of the British Empire.

That changed in 1947, when a cash-strapped Britain ended its almost century-long reign over the Indian subcontinent, a period known as the Raj.

But in granting India’s independence, Britain divided the subcontinent, drawing a new border separating India and its majority-Hindu population, from the new state of Pakistan, which was mostly Muslim.

Known as the Partition of India, the sudden change created a massive surge of violence, migration and displacement, the repercussions of which are still felt today. Between 200,000 and one million people were killed, according to the BBC, some in communal violence, and others from disease in refugee camps.

In Broken Threads: My Family from Empire to Independence, Husain documents her family history during that turbulent time, and how it has shaped the lives of her grandparents and parents, and even her identity today.

The following is an excerpt from from Husain’s conversation with As It Happens host Nil Kӧksal.

How did you decide to make time and space … to put this book together?

This book has been in the back of my mind for a really long time because I knew that my grandparents … lived through extraordinary times.

I begin the book with Shahid and Tahirah, my maternal grandparents, and Mary and Mumtaz, my paternal grandparents, in many ways in the heyday of British India in the early part of the 20th century.

They were born in a time where they did not think the Raj was going to end in their lifetimes. And then they grew up in the ’30s and lived through the Second World War and … the cataclysmic events of 1947, when these two couples chose Pakistan rather than India.

The reason I called it Broken Threads is that it is an attempt to recapture a part of my history, which is, to a large extent, lost to me and my family.

When you can’t really go to the places that your grandparents grew up in, and the streets they walked, or the schools they went to, I think there is a strange feeling of rootlessness that comes from that. And I felt I didn’t really have any history of my own when I was growing up in England.

All my English friends had their villages, which they’d lived in for generations. And I felt like, well, you know, where did I come from?

It’s quite moving to hear you say that, because, you know, I see you, and I think many people see you, as someone who is very much a part of the fabric of the U.K., the media landscape. And I was going to ask you if you ever felt like an outsider, despite being born there and being so intertwined and so prominent there.

I have felt like an outsider. But in a way, sometimes these things are quite hard to acknowledge, because generally you want to fit in.

I used to see myself as a daughter of an immigrant, in that my father came to the U.K. as a doctor to work in the National Health Service.

But through writing this book [I found] the passport issued in 1931 to my grandfather, Shahid, in which his national status is recorded as “British subject” by birth. Because, of course it was. Everyone born in British India up to 1947 was a British subject by birth. [But] I’d never seen him as that.

This is how I feel my sense of identity change. I now think I’m not the daughter of an immigrant; I’m the granddaughter of British subjects. That’s what this generation that I write about were.

Your wedding day. It’s an emotional time for anybody during a wedding. And then you get this gift. I mean, I’m going to cry just thinking about it.

It’s a very plain beige-coloured woolen shawl. And it was a cousin of my mother’s who gave it to me as a wedding present, Shahmeen.

When she gave it to me 21 years ago, she said: “The border of this shawl is all that remains of a sari that was given to my mother when your grandparents got married.”

Most of it had frayed over time, but just this border remained. And Shahmeen thought it would be the fitting thing to use it to edge a shawl and give it to me for my wedding.

I looked at it and I realized that this sari went from India to Pakistan at a very tough moment. Because I knew that Shahmeen had been in the care of her grandmother, and that this part of the family, in the autumn of 1947, had left their home in Lucknow in India as the security situation deteriorated. And I knew that they had just packed up a few bags and got on a train.

And I thought to myself, in the stress of that moment, as they look around their house and they think, “What are we going to take with us?” … someone thought that for this little girl, who was then six, they should grab this particular sari that had belonged to her mother and take it with them to Pakistan.

You also had … resources within the family to draw from, which are quite extraordinary as well … recordings of one of your grandmothers, tape recordings that she had made, unfinished memoirs as well. When did you realize that those existed and that you had those to work with?

As I tried to work on the story of my grandmother, Thyra, my mother came to me and said, “I found these tapes.” And they were cassette tapes.

I put the tape into the player and I pressed play and I heard her voice again. And it was like an audio memoir. Her eyes weren’t very good, and so she thought it was easier for her to talk rather than write. She was starting to record a lookback on her life and think about the events that she saw.

I’ll read you a little bit:

“I feel that before Pakistan came into being, we had a complete life. Countries have their problems, whether they’re ruled by others or by people that actually belong, and nothing is perfect. All I know is that the life I had before the Partition of India was as beautiful and as rich as it was afterwards.”

What do you think your grandparents would think of what you’ve done here with Broken Threads?

My grandfather Mumtaz, in his unpublished memoir, says right at the beginning: “I’m putting down the story of my life, but I know that none of my children or grandchildren are interested in it. I’m writing it anyway.”

I am very lucky that that account was saved from his computer when he died by one of my uncles, who sent it around to everyone in the family. And the truth is I didn’t read it then. I didn’t read it for a long time, until I really needed to read it. And when I read those words of his, I felt so ashamed, because he was right. We weren’t interested.

But I’m so grateful that he wrote the everyday aspects of life down, because all of it is interesting.

If I have one message in this, it’s that people should record their parents or grandparents talking if they possibly can. Even if you don’t have any intention to use it, just get it down while you still can.

You never know when or who is going to be interested in it, and the kind of picture it helps them build of themselves.