For more than three decades, Hizbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, whom Israel killed in an air strike, oversaw the Shia Islamist movement’s transformation from a guerrilla group into the Middle East’s most powerful transnational paramilitary force.

In his 32 years at the helm of Hizbollah, the 64-year-old cleric was credited with making it the pre-eminent force in Iran’s regional network of proxies known as the axis of resistance.

This gave Nasrallah an unrivalled position as both a public face and crucial strategist in the network — “more junior partner than proxy” in the axis, according to Hizbollah expert Amal Saad.

Rarely seen without his clerical garb, Nasrallah was viewed as one of the most important figures in the axis, second only to Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, following the US assassination of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani in 2020.

Nasrallah’s forces helped train fighters from Hamas, as well as other members of the Iran axis, including Iraq’s Shia militias and Yemen’s Houthis.

He will be remembered among his supporters for standing up to Israel and the US, and restoring Arab might. His enemies will point out that he was the leader of what they consider a terrorist organisation, which furthered Iran’s geopolitical agenda and was accused of widespread atrocities, both at home and abroad.

In Lebanon, Hizbollah is referred to as a state within a state, with a parallel network of social services that rival those of the government it has worked for decades to undermine.

Nasrallah was reviled by many in Lebanon’s Christian and Sunni communities, who blamed him for eroding the nation’s state institutions, putting Iran’s interests ahead of the country’s and turning his movement’s weapons inwards to quash dissent and opposition.

He was also loathed by many Syrians, after Hizbollah fighters helped president Bashar al-Assad’s regime brutally crush the opposition after civil war erupted there, following a 2011 popular uprising.

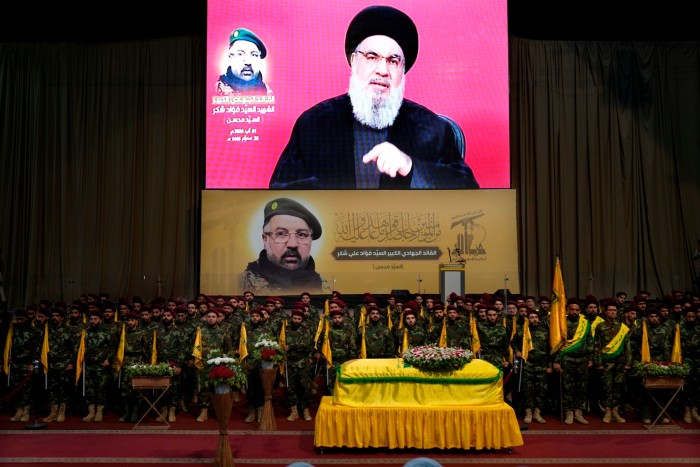

All the while, Nasrallah crafted his public image, weaponising his charisma and his battlefield victories to hone a cult of personality that led his supporters to revere him as near-omnipotent.

His face appears on billboards and key chains, mugs and candlelit shrines. Lebanese routinely trade Nasrallah stickers on WhatsApp while snippets of his speeches are often turned into memes.

The portrait painted by people who knew Nasrallah or met him over the past 40 years is of a strategic thinker with a commanding presence, a man feared and admired in equal measure, revered by Islamist militants and Middle Eastern tyrants.

Very few people met him in person in recent decades. Those who have, described Nasrallah as courteous, perceptive and funny.

A powerful orator, he spoke colloquial Arabic — not classical — while a life-long speech impediment, which left him unable to pronounce his Rs, was widely viewed as disarming.

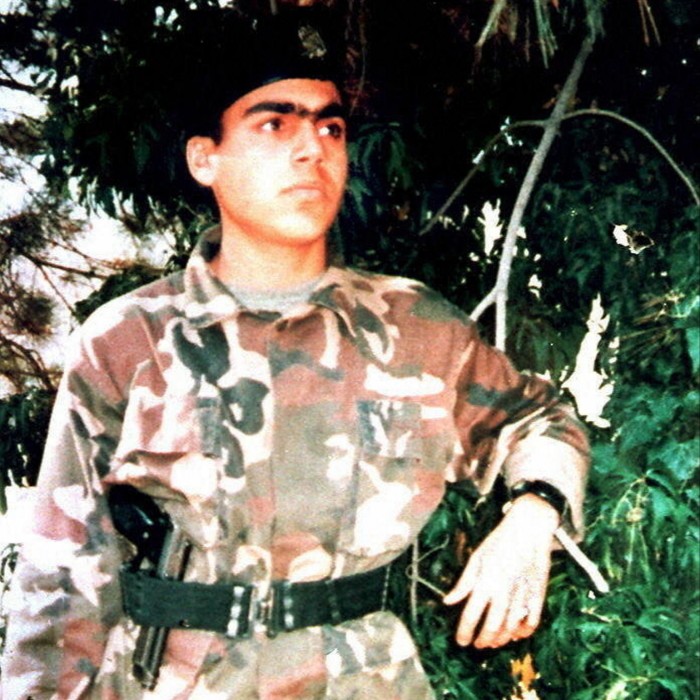

Nasrallah was born on August 31, 1960 in an impoverished Beirut neighbourhood that was home to Christian Armenians, Druze, Shia and Palestinians. He said he was “an observant Muslim at the age of nine”, more preoccupied with his prayers than helping his father in his vegetable shop.

When Nasrallah was 16, he sent himself to a seminary for aspiring Shia clerics in the Iraqi city of Najaf. He left less than two years later, fixated on resistance to Israel.

While in Najaf, he came under the influence of Abbas Mussawi, a Lebanese cleric just a few years older than him, with whom he would eventually found Hizbollah in the early 1980s.

He climbed quickly up the ranks, forging close ties with the men suspected of plotting some of the group’s earliest terror attacks — including the 1983 bombing of the Beirut barracks housing US and French peacekeepers, which killed at least 360 people.

“After 1982, our youth, years, life and time became part of Hizbollah,” Nasrallah told a Lebanese newspaper in 1993, a few months after he was appointed leader of the militant group following Mussawi’s assassination by Israel.

Unlike other paramilitary leaders, Nasrallah was not known to have personally fought. But his leadership earned him respect among Hizbollah’s ranks as a battlefield commander, particularly after his 18-year-old son Hadi was killed by Israeli commandos in 1997.

“We, Hizbollah’s leadership, do not jealously guard our children,” Nasrallah said the day after Hadi’s death, cementing his reputation as a wartime leader who was willing to make sacrifice for their cause. Nasrallah shared at least three other children with his wife Fatima.

Nasrallah’s reputation in the region grew when Israel withdrew from southern Lebanon in 2000. “He achieved what few if any Arab states and armies had done fighting Israel,” Saad said. His reputation was enhanced after Hizbollah fought Israel in a 34-day war in 2006.

This also made him one of Israel’s prime targets. He lived largely underground, “somewhere between southern Lebanon, Beirut and Syria”, to evade assassination attempts.

When thousands of Hizbollah’s electronic devices detonated this month killing dozens and maiming thousands more, in attacks widely blamed on Israel, Nasrallah was said to be unharmed. He never handled electronic devices, which were always heavily screened before being allowed in his vicinity.

He was also rarely known to answer his own phone after Israel was allegedly able to reach him on his personal landline, which exists only on Hizbollah’s parallel telecommunications network.

His frequent speeches were delivered via secure live feed to his legions of followers, broadcast from unknown locations, and he sent emissaries to meet his political allies and foes. This helped him deepen his enigmatic aura and the reverence his public had for him.

As Israel has stepped up its attacks on Hizbollah over the past year, it has killed many of the group’s leadership, targeting its field officers before taking aim its senior most command.

Almost none of the original members of the group’s jihad council, Hizbollah’s top military body that Nasrallah oversaw, is left alive, according to people familiar with the group’s operations.

Many Lebanese remember the destruction wrought the last time Hizbollah went to war with Israel in 2006. In the final hours before the ceasefire took hold, waves of Israeli bombs rained down over Beirut’s southern suburb of Dahiyeh. It was considered a last-ditch attempt to kill Nasrallah.

When that war ended, Nasrallah said he would “absolutely not” have launched the attack that triggered the conflict “if I had known . . . that the operation would lead to such a war”.

It was in Dahiyeh where Friday’s strike killed Nasrallah.

Additional reporting by James Shotter in Jerusalem