Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

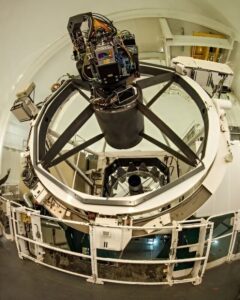

Michael Marriott’s east London studio is a wonderful mess. It’s rammed with tools, boxes, stools, signs, books and designs, prototypes of his own furniture and products and those of friends, piled all around with fascinating things. This is not one of those self-consciously showroom studios, more for effect than process, but rather a place of real ideas and work.

The designer, a dependable and much-loved fixture of London’s scene for the past three decades, makes me a strong coffee. I notice, halfway through our conversation, that the mug says The Tool Appreciation Society. “I love tools,” Marriott says. “They’re perfect objects, partly because they haven’t been tampered with by designers. They’ve evolved through use and they relate very closely to the human body, the way in which they fit in the hand.” We spend a happy few minutes talking about hammers.

His comment on the (lack of) design of tools is revealing. “I don’t really like the word ‘designer’,” he says. “Design means lots of things. Designer fashion or jeans, sometimes it’s just a colour scheme. I’m slightly ashamed to be a designer. We’re caught up in the world’s problems: overproduction, over-marketing. On the one hand I feel I should just stop. So I try to do things in a way that causes as little harm as possible. Design should be about solving problems but it becomes part of the problem, which is overconsumption.”

Marriott’s designs are often modest. They employ found objects or involve a small adaptation of an existing product, items which are useful and economical but also intelligent, sometimes wryly commenting on the broader world of design through small gestures. There are candlesticks and doorknockers made in the image of hex wrenches, for instance, a clock face made from old cardboard boxes, a lampshade made from a plastic bucket or a bottle-opener made from broken bicycle rims.

Of course, there are more conventional designs too, for furniture or shelving, the latter including his popular Croquet range, with brackets inspired by croquet hoops, but also his Olá café chair, a version of the bentwood Thonet classic. These he used in the designs for Bloomsbury’s Café Deco, a lovely space which manages to blend the proletarian-utilitarian style of a London caff with the bourgeois sophistication of a continental café.

He has a nice sideline in shop fittings (as at Leila’s in Shoreditch). “When I started out, I thought I was a furniture designer, and I think I am, by philosophy, but I like to do what I can using as little material as possible, making things that are reduced.” He has also become known for installation and exhibition design, where “you’re working with a curator and a graphic designer, so you’re not just making shapes but working with a cultural context too. And there’s also a fee . . . ”

What there often isn’t is a place to sell some of the more eclectic or eccentric designs: the smaller, quirkier things. Marriott addressed that with his online shop WoodMetalPlastic.

“That’s what these things I do are made of. At first we were just selling pieces like the Ernö hook [a tough, injection-moulded double wall hook] but then we started with other pieces like this camping tin-opener from Spain which was old stock; the manufacturer closed down in the 1960s, so these were probably the last of these things in the world.” There are also plenty of other wonderful, everyday, simple things: plastic bowls, brushes, lemon squeezers, brightly coloured but unselfconscious. And also inexpensive. This is not the world of Milanese high design but of good things made accessible. (I like the Kex cabinet handles adapted from brass radiator keys, £5.95 each, designed by Kitty Hiscox.)

For a long time Marriott taught at London’s Royal College of Art, where he studied, and his impact has been felt widely. He has always provided the antidote to the starry designers of self-conscious icons, the jet-setting names who think their work blurs boundaries between design and art and see their statement sofas sell for big money at auctions. But when I ask him about his effect on the London design scene, he modestly demurs. “I don’t see it myself,” he says, “but I have been told by others.”

In fact, he is very much a London designer. “I was born here,” he says, “and though I grew up in the suburbs [Dartford, Kent], I came back as soon as I could and have been here ever since.” There is something about his wit, the slightly sly take on the culture of consumption which he so successfully subverts with his designs, that has a hint of London’s ad hoc, almost punkish spirit. His shop had a presence during Milan’s Salone del Mobile this year, a lively storefront which was one of the sprawling event’s highlights (partly by being everything the design industry at large is not).

I pick up a pepper grinder from the table, a thing that was hiding behind my mug. It has a head shaped like a nut. “I know, the world doesn’t really need another pepper grinder,” he says, “but I’m more interested in how these things sit in a landscape of objects. How does it speak to the other objects on the table?” I look at the things around it: another mug, an Opinel knife, a handwoven basket, a book, a bent-metal oil and vinegar set-holder. Some are his designs, others he sells in his shop, others still are the workmanlike, useful objects he loves and lives with. It seems to me like they’re all having a pretty convivial conversation, at least as much as objects can.

michaelmarriott.com