Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Global Economy myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Governments need to cut spending and raise taxes to bring down debt and recover the fiscal firepower needed to respond to future economic shocks, the OECD has warned.

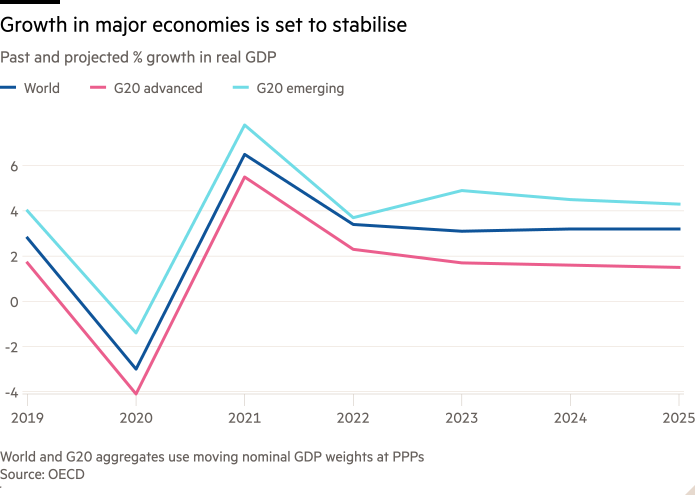

Large economies have now “turned the corner” in tackling inflation, the Paris-based organisation said on Wednesday. In its new forecast, the OECD said price pressures would continue to ease and global GDP growth was set to stabilise at 3.2 per cent in 2024 and 2025.

This should create space for central banks to continue cutting interest rates, although the timing and pace of reductions would need to be “carefully judged”, the OECD said. But it urged governments to step up efforts to contain spending and boost tax revenues to rebuild fiscal buffers.

“Fiscal issues have not been given enough importance in the past few years,” said Álvaro Pereira, the OECD’s chief economist, noting the growing pressures of ageing populations, climate change, rising defence spending and higher debt service burdens. “The sooner the better in restoring fiscal discipline.”

The OECD’s intervention came against a backdrop of growing alarm over France’s ability to close its budget deficit, with Paris asking for a delay in submitting its plans on how it will comply with EU rules.

Bank of France governor François Villeroy de Galhau on Wednesday said it was “not realistic” for the French deficit to meet the EU rule of 3% of its GDP in the next three years, but that this could be achieved within five years.

France’s 10-year bond yields traded at the same level as those of Spain on Tuesday as finance minister Antoine Armand said Paris was looking at ways to raise new tax revenues from the wealthy and from corporations to tackle “one of the worst deficits in our history”.

Pereira declined to comment on France’s situation but said it was “certainly very possible” for high debt levels in certain countries to lead to market upsets.

“We are advocating fiscal discipline, not the return of austerity,” he added. The OECD believes many countries need to reform pension and wider welfare systems, while raising more revenue through indirect and property taxes, and scrapping tax exemptions.

The end of the inflationary crisis is not yet guaranteed, however, Pereira warned: in many countries, a decline of 1 percentage point or more in services price inflation was still needed to bring core inflation back to rates consistent with central banks’ targets.

There was also a “disconnect” between the direction of policy and people’s daily experience in countries where wages had not yet caught up with food prices, he added, noting. “People still feel the pinch when they go to the supermarket.”

Meanwhile the relative reliance of global growth hides a sharp transatlantic divergence. The US economy is set to grow by 2.6 per cent in 2024 and 1.6 per cent in 2025 on the new OECD projections, while the eurozone is expected to grow by just 0.7 per cent this year and 1.3 per cent in 2025.

Pereira said one route to lift long-term growth would be to break down barriers to competition in the services sector — especially in regulated professions and in energy, telecoms and transport.