For the last decade Wiltshire Council has hit central government-imposed housing targets and built around 2,000 homes a year. Now this rural region of south-west England is bracing itself for a housing revolution.

Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer has pledged to bust through the UK’s sclerotic planning system to “get Britain building again”, including by imposing tougher house building targets on local councils.

The ambition is bold, but in Wiltshire officials, councillors and builders say their new target of 3,476 homes a year — an increase of 81 per cent — is unrealistic without more far-reaching reforms than Labour has so far outlined.

“We can never deliver that number of houses, ever, and we’re a pro-building county” said Nic Thomas, director of planning for Wiltshire, a Conservative-controlled local authority responsible for 500,000 people, half whom live in small towns and villages.

A day spent at Wiltshire’s County Hall headquarters in Trowbridge, talking to officials, politicians and planning agents reveals the complex web of problems that have thwarted governments of all political stripes from hitting their housing targets over the last 40 years.

These include developers seeking to control the supply of new homes; infrastructure shortages that hold up developments; and a decline in staffing at local planning departments just when new environmental regulations have made approving fresh projects ever more time-consuming.

Labour has promised to deliver 1.5mn homes in its first five-year term, driven by reforms that housing secretary Angela Rayner told the party conference on Sunday would deliver “decent homes for working people”.

The plans include allowing building on “ugly” parts of the protected greenbelt, limiting aesthetic objections from local councils, and prioritising “critical” infrastructure projects.

Parvis Khansari, the director of place at Wiltshire, is sceptical that Labour’s reforms will come anywhere close to cutting the Gordian knot of problems that have held back house building for decades.

“The proposals from the current government are really just doing more of the same, but a bit better,” he said. “It’s radical in terms of the numbers — they are incredible — but just not in terms of actual delivery.”

Getting the builders to build

Delivering change will require braver steps to empower councils to force developers to actually build on the sites where they have already been given permission, according to Richard Clewer, the Conservative leader of Wiltshire Council.

More than a million homes given planning permission in England and Wales since 2010 have not been built, according to an analysis of planning applications by the Local Government Association.

Wiltshire currently has given planning permission for more than 16,000 homes, Clewer said, but only a small fraction of these are being built because developers “game the system” to avoid large developments that also require them to build roads, schools and other amenities.

The National Planning Policy Framework — government guidelines that set planning policy across England — requires councils to maintain a five-year pipeline of house building projects.

If they fail to do so, then a “presumption” in favour of approving residential developments kicks in, which allows developers to cherry-pick where they build, Clewer said.

“It’s become impossible to maintain a ‘five supply’ even when building 2,000 homes a year, because the developers play the system by holding back developments. They say they don’t, but they do,” he added.

The result, says Clewer, is piecemeal, “cookie-cutter” developments thrown up on the outskirts of towns like Salisbury or Warminster, rather than larger, better-planned developments.

Clewer cited a long-stalled plan for a 2,500 home development at West Ashton south of Trowbridge as an example of how difficult it was to bring forward larger projects.

The application for the development was first lodged in 2015 but nine years later negotiations are still continuing with Persimmon Homes over how much infrastructure and affordable housing the developer should provide.

Persimmon said it was working to bring the development forward as quickly as possible, but was navigating a “fiendishly complex” system for developers and local authorities alike.

The company also rejected the notion that larger developers were engaged in land banking, citing an investigation by the Competition and Markets Authority that found while housebuilders held more land than was good for a “well-functioning market” this was driven by “uncertainty” surrounding the planning process.

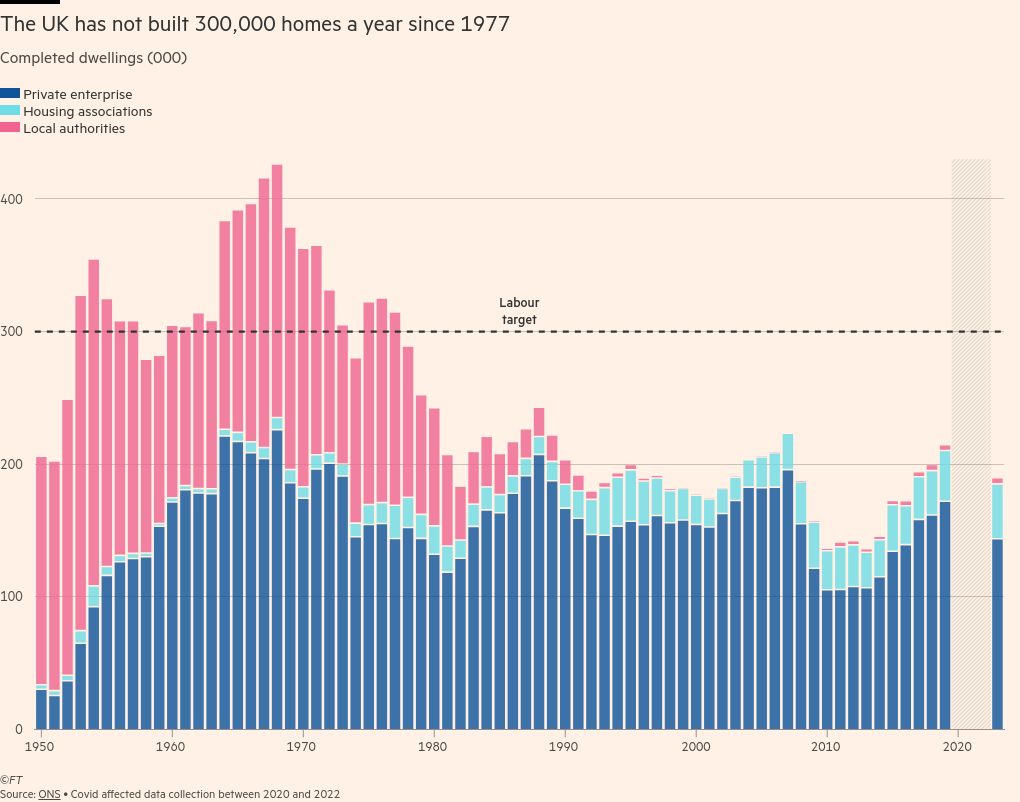

The UK last delivered 300,000 homes a year in 1977, when nearly half were built by local councils. Clewer says there no realistic prospect of that system returning, and in his view private developers won’t build at that volume under current rules.

“We need more carrots and sticks to get developers to move. It would be far easier if they lost the permissions full stop, when their option expired, or even were required to start paying an element of council tax on the unbuilt homes,” he said.

Unlocking the land

In other cases, planning officers said, the challenge is getting land promoters to release land they have optioned, but hold back in the hope of winning lucrative residential planning consents at some point in the future.

In the nearby town of Melksham, five miles north-east of Trowbridge, local businessman Sam Gompels has struggled to find land on which to expand his fast-growing medical and hygiene products distribution business.

His Gompels HealthCare business employs 80 people and has 100,000 sq ft of warehouse space. But after a boom in sales following the Covid-19 pandemic, the entrepreneur wants to double the footprint.

A field directly adjacent to current warehouses would be perfect, but Gompels and council officials said the company that has an option on the site, Gladman Land, is retaining it for future residential development. Gladman Land did not respond to a request for comment.

The council has also rejected several other alternative sites proposed by Gompels.

“We’ve already lost out on several big contracts because we don’t have the space to service them. Overall the development would bring 275 additional jobs to the area, but as it is, I spent 30 per cent of my time fighting planning when I should be out winning new business,” he said.

Jonathon Seed, Gompels’s local councillor, shares his constituent’s frustration, conceding the council could be more proactive about encouraging development for business purposes.

He added that even though it ran against his Conservative free-market instincts, it was time for the government to consider creating additional compulsory purchase order (CPO) powers.

“I don’t like it in principle, but we need to find some way of unlocking land from developers. If we have developers who are acting without any thought for the community and only in their commercial interest, then we need to find a way of addressing that,” he said.

People familiar with discussions in Whitehall said Labour was looking at extending CPO powers but one of them conceded that any reforms were still “some way off”, and required careful testing in order to be legally watertight.

A broken bureaucracy

Developers, builders, planning consultants and land agents in Wiltshire say the real block to development is time-consuming new regulations and poor service from the local council.

“Officers are not very proactive, if there’s an issue, instead of trying to find a solution, they just refuse it,” said one agent at a Wiltshire Council feedback session attended by the Financial Times last week.

“Officers often engage too late in the application process, and when they do, they just kick it down the line,” said another.

Wiltshire is spending £1mn upgrading its planning services and has created 18 new roles in its planning department since February. But the investment comes after years of cuts to local government funding since 2010.

Labour has said it will hire 300 new planning officers, but this would replace only a tiny fraction of those lost to the system during the austerity years and would do very little to address staff shortages at a national level.

At the same time as planning services have shrunk, the burdens on them have increased massively with developments now requiring complex evaluations about their impacts on biodiversity and water pollution.

Councillor Nick Botterill, cabinet member for strategic planning, said a recent trip to the archives had revealed how much more paperwork modern planning consents required.

“It was a development for 20 houses done in 1980. It was typed on three pages and on the back, someone had simply written ‘condition discharged’ and a date. Applications now cost hundreds of thousands of pounds to prepare and can run to hundreds of pages,” he said.

One developer cited the example of the Jubilee Gardens development outside Warminster that was impacted by “nutrient neutrality” rules. They require builders to mitigate the amount of phosphates leaching into the water course as a result of sewage.

Planning approval was delayed a year after Natural England, the government’s environmental adviser, queried the phosphate mitigation plan.

“The expensive bit is time. Waiting for approvals means I have to demobilise and then remobilise construction teams. I would pay 10 times the fees if I could get guarantees on how long approvals were going to take,” he said.