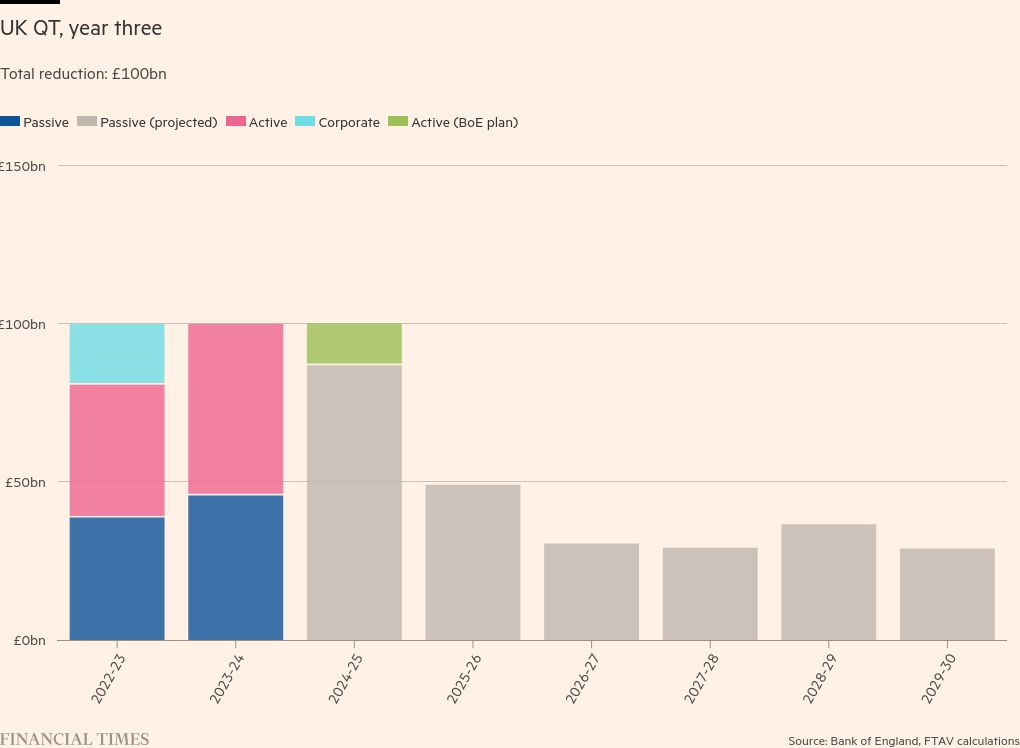

The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee today announced it will keep its quantitative tightening envelope at £100bn.

As a result, over the coming year Asset Purchase Facility reduction will consist of £87bn of bonds maturing and rolling off, and £13bn of active sales. From the summary:

The MPC also reaffirmed that there would be a high bar for amending the planned reduction in the stock of purchased gilts outside a scheduled annual review. That was in order to remain consistent with the principles that Bank Rate should be the active policy tool when adjusting the stance of monetary policy, and that APF reduction should be predictable.

This is what was expected (albeit not universally) so isn’t a huge shock. However, because the UK is a silly country, it might matter hugely.

Here are two things.

First, from Szu Ping Chan, a former colleague of the author, at the Telegraph:

Rachel Reeves has been handed a boost of up to £10bn ahead of the Budget after the Bank of England said it was slowing down sales of government bonds amassed during lockdown.

Second, from Tom Rees, a former colleague of the author, at Bloomberg:

[T]he BOE sticking to a £100 billion run-off for a third year means the OBR could adopt a new assumption that this pace continues going forward. Bloomberg Economics calculates that this would reduce the chancellor’s already thin headroom by a further £5.5 billion.

So, £15.5bn of fiscal headroom swing — money that can be spent on things like hospitals for sickly orphans, or hospitality tickets for Keir Starmer to go see Arsenal play — hinges on assumptions made by the OBR.

Two key points that you probably all know by now:

— QT is bad for the government because QT makes the BoE lose money, and the Treasury has to indemnify those losses.

— The UK’s fiscal rules dictate that public debt must be falling at the end of the five years following a fiscal event, meaning it is straitjacketed by projections made by the OBR, the government’s fiscal watchdog.

And time to tap the sign so we’re all on the same page:

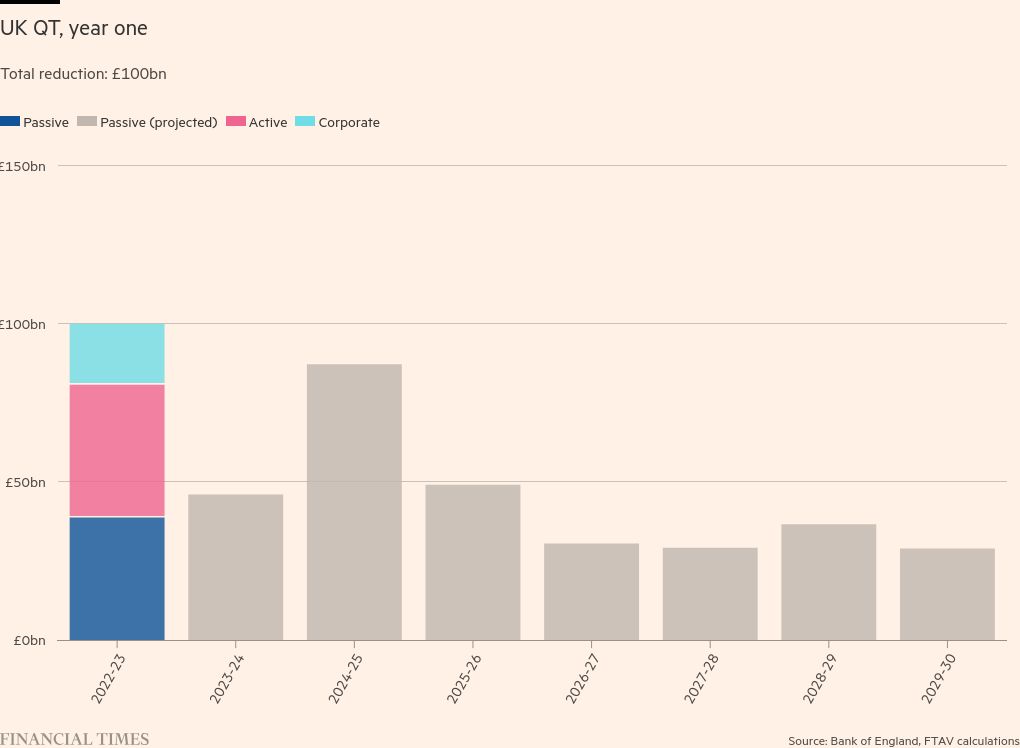

Let’s quickly unpack how we got here. The Bank of England launched its active quantitative tightening process in autumn 2022. In the ensuing year, it reduced the APF by £100bn, comprising about £39bn in maturing bonds rolling off, £42bn in active gilt sales, and £19bn in corporate bond sales (thanks for Pantheon Macroeconomics’s Elliott Jordan-Doak for helping us pull these numbers):

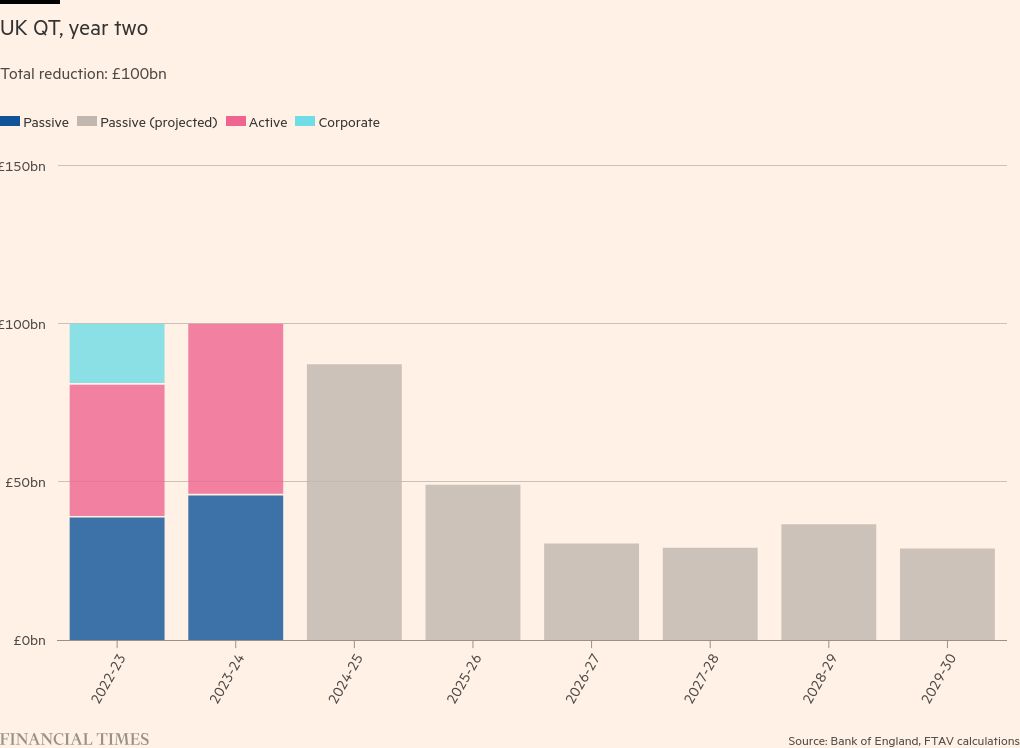

In the programme’s second year (which is now coming to an end), it is reducing the APF by £100bn, comprising £46bn in maturing bonds rolling off, and, by implication, £54bn in active gilt sales:

That the Bank of England’s target for the current year is £100bn has been known since last September.

Armed with these pieces of information, the OBR (the decisions of which are material because they determine the amount of headroom available under the fiscal rules) had to make a call ahead of its March economic and fiscal outlook: which was more likely — that the BoE would continue to aim for £100bn of reduction per year; or that the BoE was agnostic to the pace of passive roll-off and instead would aim to keep a consistent level of active sales?

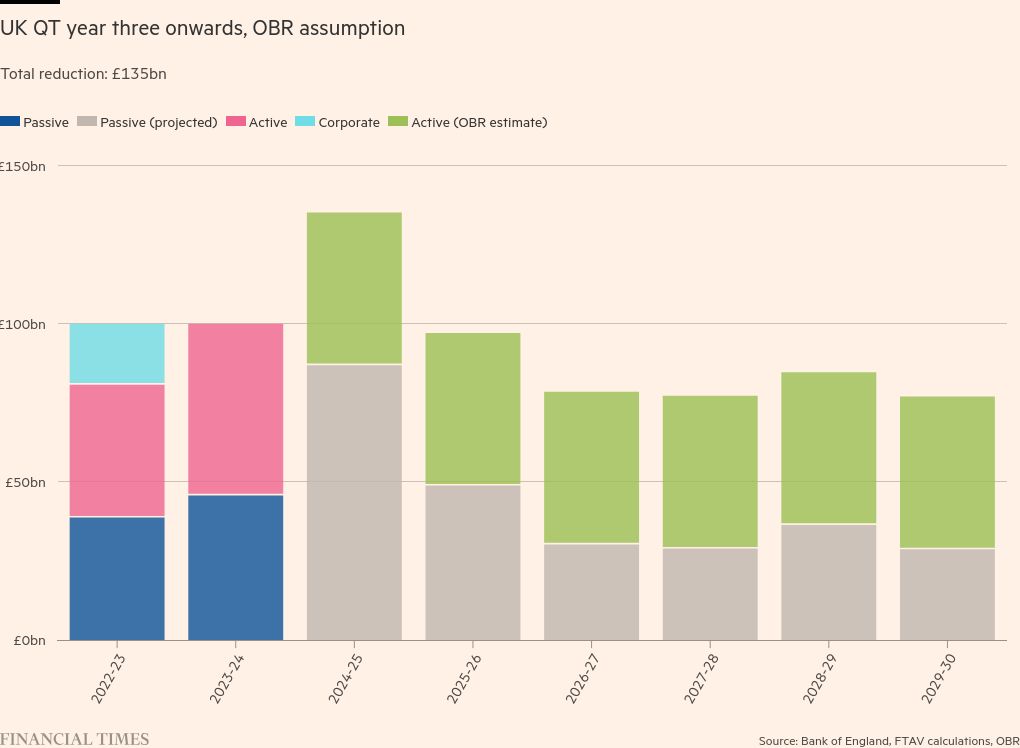

It chose the latter, determining — by a simple average of the first two years’ outcomes — that the BoE would decide to undertake £48bn of active sales in QT’s third year, taking the overall envelope to £135bn (£87bn passive + £48bn active).

With the benefit of hindsight the continuation of a £100bn per year pace of reduction seems obvious. But there were credible arguments for both scenarios (when the BoE set out the £100bn envelope for year two, minutes note “the Committee placed some weight on continuity in the pace of sales”), and the sellside has been full of murmurs all year about which way the MPC would decide to go. We don’t really blame the OBR for choosing the one they did, but we must live with the consequences.

However, it has also long been known that the third year of QT would be a weird one: that’s because an unusually large number of gilts held in the APF are due to mature — the £87bn we referred to earlier.

So we face a major slowdown in active sales in the coming QT year. What are the consequences?

Well, that’s up to the OBR.

Quickly, it’s worth another reminder of why the UK’s fiscal rules suck: things only matter on a rolling five-year horizon, meaning present decision-making is constantly hostage to assumptions and extrapolations across a half-decade timespan. And this is a perfect example of the OBR making big assumptions about a big area.

As far as we can see, there are three obvious paths:

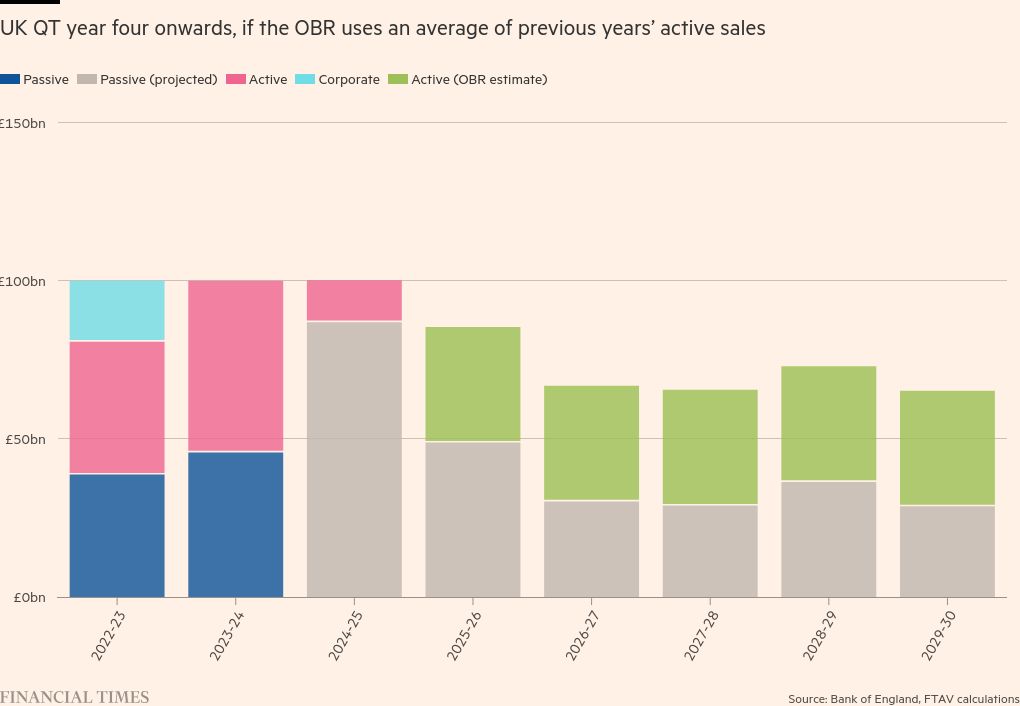

Option 1) The OBR sticks to its previous methodology, and when estimating the future pace of sales averages the first three years (£42bn, £54bn, and £13bn). That would give it a figure of £36.3bn in active sales per year, a kind of middle way:

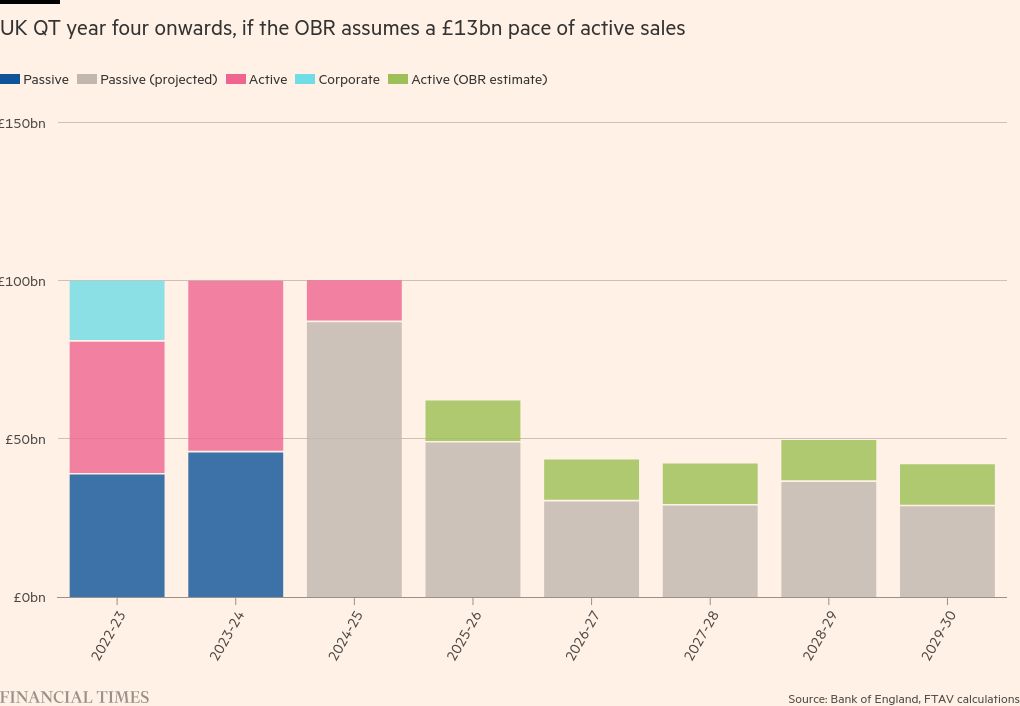

Option 2) The OBR assumes £13bn of active sales is the pace going forward. This is the rather, dare we say, optimistic estimate deployed by Goldman Sachs in a June note that is the basis for the Telegraph’s piece — and the ideal one for Chancellor Rachel Reeves:

As Goldman wrote then:

We estimate that if the OBR were to instead assume a £13bn pace of active sales going forward, then that drag would reduce by around £10bn. We think the next government would likely use the additional fiscal space to slow the pace of fiscal consolidation.

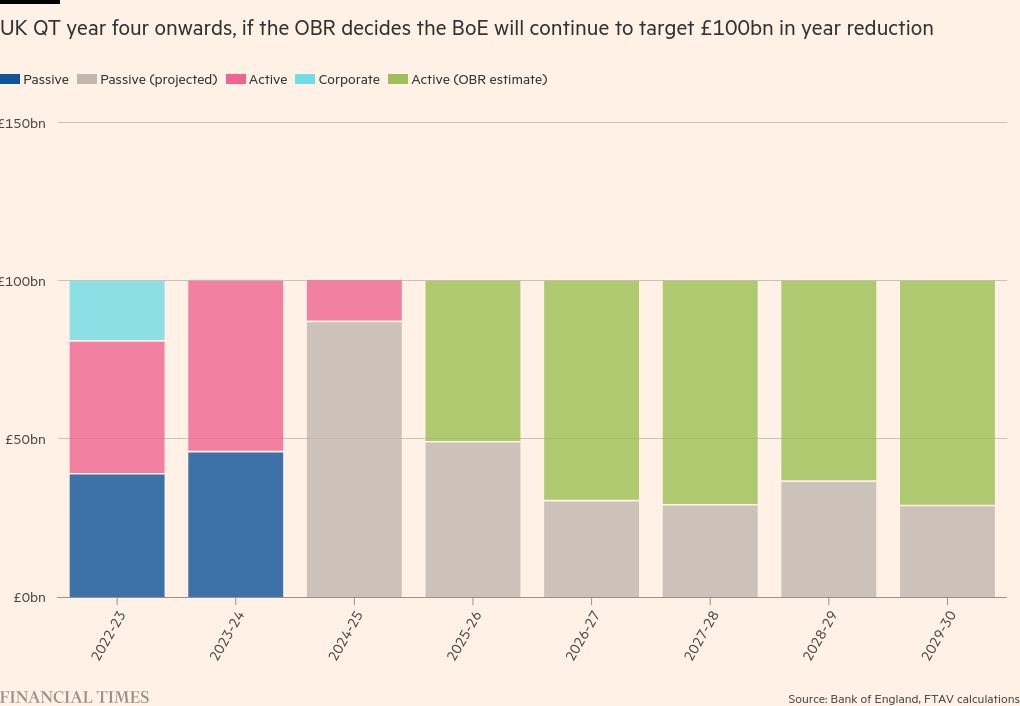

Option 3) The OBR takes the EXTREMELY STRONG HINT from three consecutive years of this being the policy that the BoE will continue to target £100bn of overall reduction, and therefore vary its active sales over the coming years to meet that target:

This would also seem to be the most bearish outcome possible in terms of the implications for the public finances. As Bloomberg Intelligence’s Dan Hanson, who created the assumption used in Bloomberg News’ piece, wrote earlier this month:

[If] the OBR decides to adopt that assumption going forward, it would reduce the already limited headroom by £5.5 billion.

Now, there’s a good chance that this will all become irrelevant, if Reeves takes the advice of those such as our learnèd MainFT colleague Chris Giles and changes the measure of debt the government targets to exclude QT losses. As he wrote last month:

It goes without saying that the UK should not set fiscal policy based on the OBR’s forecast on QT five years into the future.

We agree! And it’s even worse if said forecasts are based so heavily on total guesswork by the OBR, and even worse given it’s based on assumptions of the scale of policy that might suddenly stop when the BoE reaches its preferred minimum range of reserves (or before).

So let’s hope for a change, lest the OBR goes big and the Emirates soon finds itself down Ødegaard and Starmer.

Further reading:

— Does the Bank of England have a plumbing problem? (FTAV)