This article is an on-site version of our The State of Britain newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every week. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Good afternoon. Difficult times for Sir Keir Starmer’s new government which seems perilously close to being engulfed in the kind of petty scandal and infighting that so paralysed and distracted the Tories in recent years.

Clearly, that superficial comparison ends with Starmer’s huge parliamentary majority, but the similarity is that clouds of media controversy about relative trivialities — freebie frocks and tickets to watch Arsenal — are obscuring the actual policy agenda of the government.

Starmer might argue that the fact he finds himself fighting such fires is a reflection of the superficiality of the UK political media, but I’d counter it is also a function of his failure to establish a strong counter-narrative about his actual plans to rebuild Britain.

Labour came to power offering an antidote to the “chaos” of the post-Brexit years. The manifesto was simply entitled “Change” and promised to rebuild Britain, “tearing down” the barriers to trade with Europe, investing in skills and future industries as part of sweeping plans to expedite the UK’s path to net zero and build 1.5mn homes.

A lack of momentum

It was uplifting stuff, even if it lacked detail, and as one senior executive said to me this week, the business community embraced the prospect of a Labour government despite the fact it almost certainly meant higher taxes and more entitlements for workers.

But since taking power, Labour has broadly failed to create a sense of momentum with the public that — for all the caveats that this is going to be a long journey and the public finances are tight — it is taking the first steps on the road to a better Britain.

This week, a group of leading economists warned in the Financial Times that cutting investment would damage the “foundations of the economy”. They were followed by Manchester mayor Andy Burnham chafing against the mentality under which the Treasury was “saying no to everything”.

The overwhelming narrative since July 4, both externally but also internally across Whitehall, has been about retrenchment not rebuilding.

‘Austerity lite’

The government has promised an industrial strategy backed by a statutory council — something that is widely supported by business groups — but there has been a conspicuous lack of detail about how it will work and whether it will have real clout to “join the dots”.

That means bringing together ambitions for net zero, housebuilding and targeted investment in key growth sectors such as artificial intelligence and life sciences, with a coherent package of policies on skills, planning reform and infrastructure investment that are designed to serve that end.

Work is continuing in all of those areas, often under a series of reviews and consultations or interim bodies, such as Skills England, which themselves become a mechanism to deflect difficult questions from stakeholders over where the government intends to invest.

In the meantime, the headlines are consumed by negative news, such as the cancellation of the supercomputer, the failure to appoint an investment minister or a chair for the Industrial Strategy Council, with ITV boss Dame Carolyn McCall the latest to turn down the job.

Even those on the inside, who hold regular meetings with ministers, are starting to grumble gently about the general lack of oomph. “There’s lots of enthusiasm and top-level announcements but really not much detail when you ask for it,” one said.

A senior Whitehall official was more direct. “The challenge on the industrial strategy is that the government seems to have locked itself into the ‘austerity lite’ plan, which then infects everything. There isn’t much evidence of an industrial policy so far.” Yikes.

You can hear a tone of frustration creeping in, even from fundamentally supportive voices such as Lord Peter Mandelson who has made a series of interventions urging the government to be bolder about driving industrial and technological growth from the UK’s research base.

In remarks to a recent Braemar Summit on the theme of “Science for Good”, Mandelson warned about the need to invest in order to “lift ourselves out of the economic mire” but also that it needed to be a broad-based approach.

“To get the growth the country desperately needs, the government should plan across the whole economy, not just the energy sector,” he said, noting that greening the economy did not, in itself, raise productivity. That required planning and investment.

And what about investors?

For investors, the current narrative — timidity on the EU reset, emphasis on spending cuts over investment and talk of raising business taxes — creates an uncertain backdrop to the investment summit the government is holding in mid-October.

There is undoubtedly a stability dividend from moving on from the Conservatives, but as one supportive executive put it, the other signals about whether Labour can really shift the dial away from the short-termism and political pettiness of the post-Brexit years are more mixed.

“It’s an interesting question. What are they going to say that is now different than under the Tories? If anything, you’d think the first steps they’ve taken — the public sector pay deals and spending cuts — make the UK a less attractive place to invest, not more,” they added.

The government might argue that these rising frustrations are themselves based on a superficial analysis of what matters.

We are told that teams are working behind the scenes on plans for Labour’s ‘five missions’ and there have been some high-quality hires along the way. Ministers, when cornered, ask for patience and promise more will be revealed after the party conferences and around the Budget.

We can live in hope, but what is less clear is why so little effort has been made in the first 100 days of Starmer’s administration to engender broader confidence that — as that manifesto title page promises — “change” is really coming.

I find it genuinely surprising. Because, as one stakeholder who works regularly (and constructively) with the government observed: “Now is the window. If they don’t come up with a plan soon, they’ll lose the crowd.”

Britain in numbers

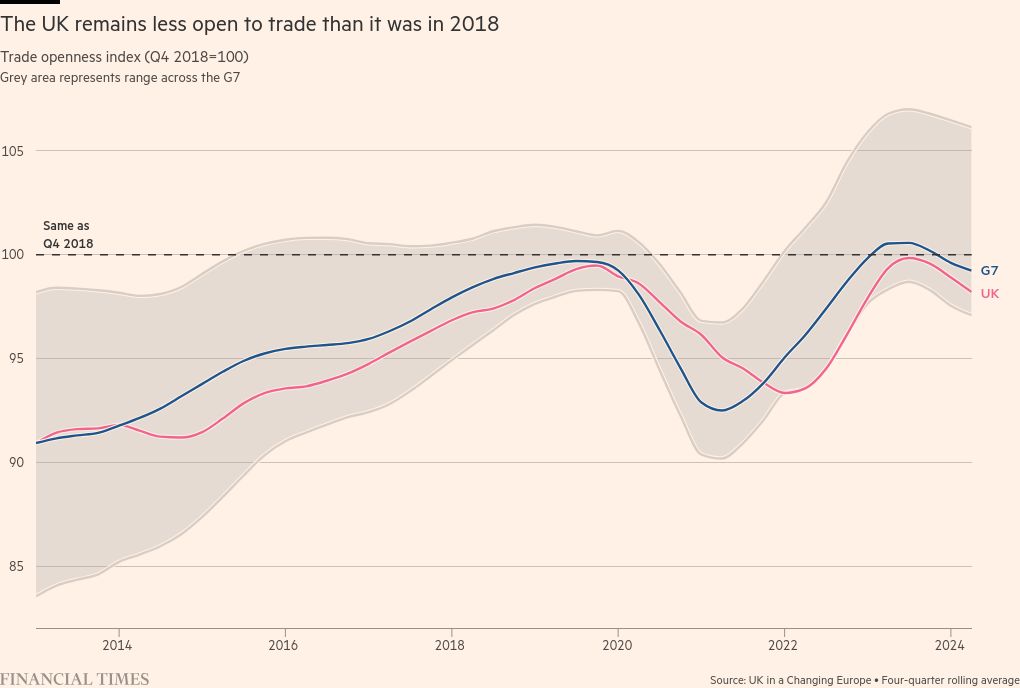

This week’s chart comes from UK in a Changing Europe’s quarterly trade tracker. It finds the UK is still struggling to surpass 2018 levels of “trade openness”, which is a measure of how open an economy is to trade.

The key takeaways from the report by Stephen Hunsaker are:

-

EU trade remains by far the biggest portion of UK trade

-

EU trade will not be supplanted by non-EU trade “anytime soon”

-

Smoothing trade relations with the EU will “help at the margins” but not “shift the needle significantly”

While it is true that the US has also been unable to surpass its 2018 levels of trade openness, he warns the comparison provides scant comfort, because the US is a far more insular economy in the first place.

The UK does not enjoy the same position, which is why, Hunsaker writes, “the UK’s relative underperformance is a serious concern for the new Labour government”.

Equally of concern in the Department for Business and Trade this week will be the latest technical analysis by Jun Du at Aston University that shows the persistent and continuing effects of Brexit on the UK’s goods trade and supply chains.

On the positive side, it shows advanced supply chains such as aerospace and autos are holding up better than other sectors, but given the direction of travel — and the UK’s desire to attract investment — it is not clear how long that will last given incoming challenges, such as the unsynchronised introduction of carbon border taxes.

All of that will be food for thought as the UK embarks on its self-limited reset with the EU, which — as trade specialist and former UK official David Henig sets out elegantly here — will be piecemeal but nonetheless important if both sides can find a way to scope out an agenda with Labour’s red lines.

More realistically, as the practical limits of the discussion on improving the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement become clear, it may be that greater dividends are found in the UK taking unilateral steps to digitise and streamline trade.

This report from Chris Southworth and the International Chamber of Commerce on the benefits of digitising trade spells out what might be achieved with concerted efforts. It’s also an area where a “nimbler” UK has a chance to lead outside the EU.

All of this raises broader questions about the complex trade-offs that will confront the UK as it cements its position outside the EU in the coming parliament, following a period of relative stasis under the Conservatives.

Which makes it doubly baffling that the Economic and Social Science Research Council has decided to pull its funding from UK in a Changing Europe from April next year, just at the point when things were getting interesting!

Like a lot of people who have benefited from UKICE’s work over the past eight years, I sincerely hope the ESRC reconsiders or another funder can be found. There has never been a greater need for clarity of thought in the debates over Britain’s future.

The State of Britain is edited by Gordon Smith. Premium subscribers can sign up here to have it delivered straight to their inbox every Thursday afternoon. Or you can take out a Premium subscription here. Read earlier editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Your essential guide to money, interest rates, inflation and what central banks are thinking. Sign up here

Swamp Notes— Expert insight on the intersection of money and power in US politics. Sign up here