Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Japan has emerged from its hottest summer to its biggest rice shortage in 30 years, with empty shelves, surging prices and the government imploring shoppers not to panic buy.

Supermarkets have limited customers to one bag at a time amid the shortages, which have been variously blamed on an influx of sushi-hungry tourists, extreme weather and decades of misguided agricultural policy. Online shoppers have had purchases abruptly cancelled or faced “lotteries”, where only some buyers get the rice they have ordered.

Private sector inventories in June were at their lowest level since comparable records began in 1999, while standard 5kg bags of Japanese rice now cost about ¥3,000 ($21), up to 60 per cent higher than a year ago.

“People in a panic must be buying more rice right now than they are ever going to eat. But I understand why,” said Minami Ota, a shopper in Tokyo’s Bunkyo ward who had visited four stores before securing a bag of lower quality domestic rice than she would normally buy.

“Even if you don’t eat it every day, Japanese like to know it is there in the house.”

Government officials have said they are reassessing the resilience of the food system in Japan, which only meets 38 per cent of overall demand with domestic supply. Japan is self-sufficient in rice and the government carefully controls imports while seeking to limit production to keep prices high.

Japan had neglected its rising susceptibility to food-related shocks, said Kazuhito Yamashita, a former top official at the agriculture ministry and now a fellow at the Canon Institute of Global Studies.

“Japanese policy of deliberately reducing production to support prices has put the country in a position where relatively small changes in the supply or demand side of rice can cause these quite severe effects,” he said.

“We chose our current situation,” said Yamashita, adding that with different policies, Japan could have become a rice-exporting superpower, with twice as much output, massive reserves and a global role in reducing food insecurity.

Japan’s rising numbers of foreign visitors are one factor driving up rice consumption, which reached 6.9mn tonnes in 2023. A record 21mn tourists visited Japan between January and July this year with collective spending on food and drink in the April to June period roughly 75 per cent higher than the same quarter in 2019. Foreigners may now account for an additional 100,000 tonnes of rice demand a year, said rice experts.

And while overall yields from the 2023 rice harvest were close to average, heavy rain and intense heat had made much of the crop unsaleable. The damage may have taken an additional 200,000 tonnes out of circulation, said Yamashita.

Meanwhile the total amount of land given over to rice cultivation has been falling. Successive Japanese governments, relying heavily on rural voters, have subsidised farmers to let paddies lie fallow in a so-called “set aside” programme.

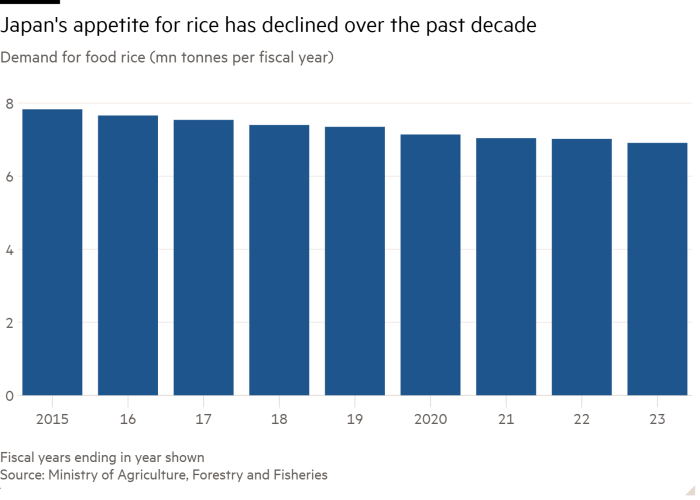

The policies have been justified by a combination of the shrinking population and changing taste. For all of rice’s cherished role in Japanese cuisine, the country has been turning away from it for decades — since 2014 households have spent more each year on bread than on rice, according to the statistics bureau.

Rice consumption has been falling at about 100,000 tonnes per year — roughly the same amount by which the government artificially reduces production.

At the same time, farmers, whose average age is almost 69, are dying out. Rice farms are going out of business at what research group Teikoku Databank says will be a record rate this year, as fertiliser and energy costs rise.

“If the situation continues, there is a possibility that a stable supply of rice will not be possible in the future,” warned Teikoku analyst Daisuke Iijima.

Immediate relief on the supermarket shelves may be on the way as this summer’s crop is harvested and rushed into stores over the coming weeks. But experts said that would mean an early drawdown of supplies and could create shortages again next summer.

“In May this year, when the rice that is being harvested now was planted, the government didn’t think there would be shortages, so there was encouragement to reduce production in 2024 too,” said Yamashita.