Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Global inflation myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Last month, George wrote about the Institute for Economic Affairs’ Shadow Monetary Policy committee: a bunch of dudes who (until recently) just wanted to chat about economics and for some reason need the backing of a think tank that won’t disclose its funding to do so.

Certain Shadow MPC members were slightly unhappy about us covering their newfound interest in directly lobbying the Bank of England. In particular, the article’s allusions to the patchy links between money supply and inflation caused some apparent consternation.

So Alphaville, which is of flexible ideology, would like to issue the following apology: monetarists of Britain, we’re sorry if we hurt your feelings.

But of course our views matter little, so thankfully Martin Wolf has come in with a spirited defence of the role of money in his column today:

In this case, the fiscal and monetary responses to the Covid shock were strongly expansionary. Indeed, the pandemic was treated almost as if it was another great depression. It is no surprise therefore that demand soared as soon as it ended. At the very least, this accommodated the overall effect of price rises in scarce products and services. Arguably, it drove much of the demand that generated those rises…

This was a global monetary glut. Nothing, Milton Friedman would have said, was more certain than the subsequent “supply shortages” and soaring price levels. Fiscal policy added to the flames. Yes, one cannot steer the economy by money in normal times. But a paper from Bruegel suggests that it is in unsettled conditions that money matters for inflation. The Bank for International Settlements has argued similarly. Thus, big monetary expansions (and contractions) should not be ignored.

The Bruegel paper is here, the BIS one here. Together, they and common sense make a compelling case that money supply matters in certain ways in certain contexts. We’re not sure we’ve ever seen someone argue that it’s totally irrelevant, and we certainly didn’t suggest that.

However, it’s worth noting that both papers are pretty inconclusive. The BIS toplines:

The strength of the link between money growth and inflation depends on the inflation regime: it is one-to-one when inflation is high and virtually non-existent when it is low.

Which sounds like a win for focusing on the money, except their actual findings and conclusion introduce a lot more nuance:

The findings above should be interpreted with great care and caution.

First, they say little about causality. The debate about the direction of causality in the link between money and inflation has not been fully settled. The observation that money growth today helps to predict inflation tomorrow does not, in and of itself, imply causality (eg Tobin (1970)). Causality is neither necessary nor sufficient for money to have useful information content for inflation – which is our focus here…

Second, the findings are based on just one episode, albeit one that is broadly shared across countries. The acid test will come in the years ahead. Having said all this, the findings give pause for thought. Might the neglect of monetary aggregates have gone too far? In the end, only time will tell.

The Bruegel piece — which was published in autumn 2021, during the heyday of Team Transitory — says:

Overall, while, in contrast to the quantity theory of money, there is no constant relationship between money and inflation, in unsettled monetary and inflation conditions monetary developments do provide information relevant to inflation. However, it is not the sporadic extreme observations that matter, but a sustained pattern of high volatility…

Currently, notwithstanding the recent increase, no pattern of inflation variability prevails, hence the acceleration of money provides no evident sign of coming inflation.

Basically, there is a lot to consider, which is more or less always the way things end up with macroeconomics.

Which may leave you wondering why this is an Axes of Evil article.

Well. Here’s part of the intro to the Bruegel piece:

In the view of economists, money seems to have lost its relevance for forecasting, let alone explaining, inflation…

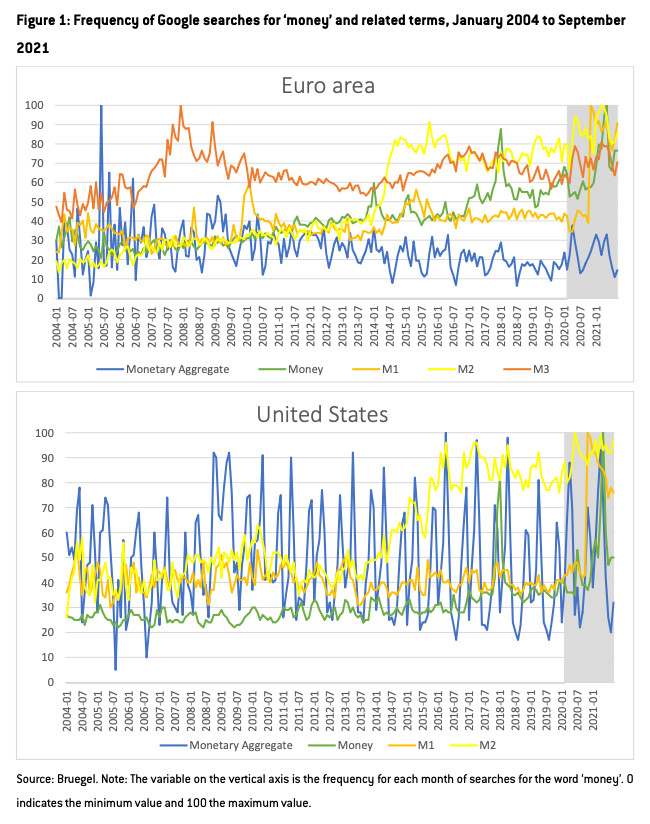

However, a Google search for the word ‘money’ and its cousins (monetary aggregates, M1, M2, M3) for the euro area and the United States is not consistent with this irrelevance hypothesis. The frequency of the word ‘money’, in particular in its narrower definition of M1, has increased quite abruptly since the end of 2019 (Figure 1).

The authors provided the following charts:

Let’s ignore the fundamental problem in the premise (when most people Google “money”, are we sure it is because of their curiosity about macroeconomic fundamentals?), and focus on the very silly bits.

Yes, that is an absolutely huge spike in searches for M1 in autumn 2021. Hypothetically, which do you think is the more likely reason?

a) As inflation picked up, the Western world suddenly took a keen interest in levels of narrow money.

b) The launch of Apple’s M1 computer chipset in November 2021.

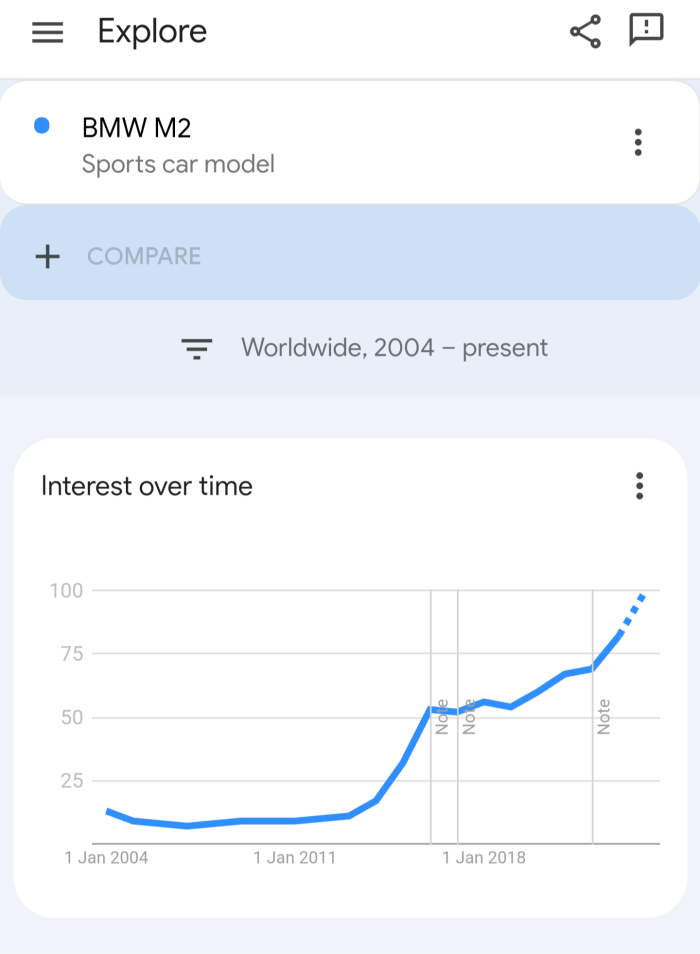

And isn’t it strange that interest in M2 picked up so much in the mid-2010s?

Maybe this chart will help provide a clue:

The real lesson here is that, in money as in all things, it’s a good idea to keep an open mind.