Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A common misconception is that the summer news lull ends as soon as September arrives. In actuality, the first week of the September is often the nadir, before kids settle into school and people working in finance get back on their bullshit.

So let’s rewind to last week. On Thursday, the Office for Budget Responsibility — the UK’s fiscal watchdog and, thanks to the exceedingly bad choices of successive governments, the key arbiter of its entire economic structure — released a discussion paper: Public investment and potential output.

The paper lays out how the OBR accounts for public investment in its forecasts, focusing on its modelling of lags and transmission mechanisms (something it has previously been doing on a something of an ad-hoc basis).

Its authors write:

This paper explores in greater depth how changes in public investment can affect potential output and seeks feedback on our proposed approach to reflecting this more explicitly in our forecasts…

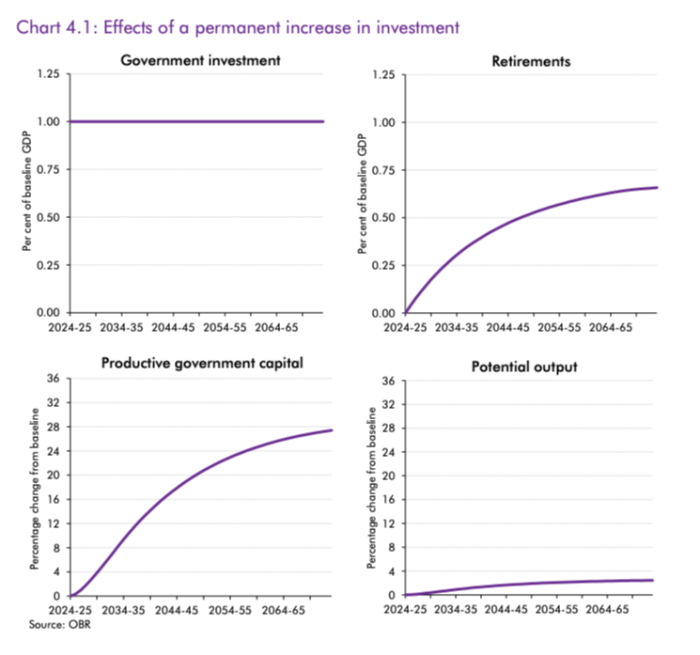

We use a calibrated model to simulate the impacts of a stylised unit shock to public investment of +1 per cent of GDP. The impact of cuts to public investment can be estimated using the same tools and would be symmetric. In our initial, high-level, and partial equilibrium analysis, we find that a sustained 1 per cent of GDP increase in public investment could plausibly increase the level of potential output by just under ½ a percent after five years and around 2½ per cent in the long run (50 years).

Oddly, OBR chooses to present this in a way that de-emphasises the growth impact (why can’t each of these charts have its own Y-axis?):

Grumbles aside, let’s tackle the 50-year forecast first. This feels like a potentially significant intervention, not least because it gives politicians an investment rule of thumb that is easy to convey: a pound invested today will be worth nearly three pounds in fifty years. Sure, there are better rates of return available, but it’s not bad as a pitch for borrowing to invest.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. As Keynes didn’t quite write, in the long run nothing matters because the only things that do matter are the rolling five-year windows dictated by the UK’s nonsense fiscal rules.

So, to the 5-year view… well, it’s basically as close as the OBR is going to get to giving Chancellor Rachel Reeves a green light to invest. As Barclays’ Jack Meaning and Abbas Khan write:

If this is carried over into the OBR’s budget analysis it would mean that the chancellor could borrow to invest in a way that causes the fiscal rule to bite much less aggressively than if she were just expanding day-to-day spending.

One further thing to emphasise: it doesn’t matter whether the OBR is right. Because of the fiscal straitjacket the UK has put itself into, all that matters is that the OBR thinks this is right. Their convictions set the bounds of economic possibility.

While we’re on the topic of borrowing:

(Bloomberg) — The UK pulled in more than £110 billion ($144 billion) of orders for a new bond sale Tuesday, in a sign investor appetite for government debt remains strong after Labour won a landslide election in July.

The country’s Debt Management Office raised £8 billion from a gilt maturing in January 2040 with a 4.375% coupon. The security, the first new bond sold via banks since the election, priced at 4 basis points over comparable notes. The orderbook matched a record set in June and is the biggest-ever demand compared to the size of the sale, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Now, as mainFT’s Mary McDougall wrote for FTAV earlier this year, these demand numbers are often something of a mirage, likely a product of hedge funds over-ordering to get the best slice of a limited allocation.

But still — the demand is there, the OBR is basically saying go for it, and the good-vibe credits can still be cashed in.

(Side note: gotta hand it to the Telegraph for this headline with regards to today’s sale in the context of a broader shift from 25-year to shorter-dated bonds:

)

Coda

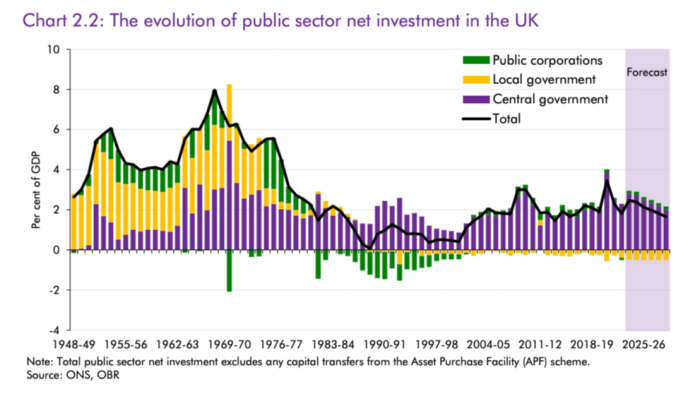

This chart, from the paper, showing the wipeout of local government and public corporation investment, is unsurprising but still pretty eye-catching: