Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Global shipowners are racing to tighten scrutiny of Chinese shipyards as soaring demand for liquefied natural gas carriers forces them to turn to inexperienced manufacturers in the world’s second-largest economy.

Shipping groups around the world are looking to tighten the reins on the shipyards to ensure they meet global standards for the construction of LNG vessels.

The shipping groups are trying to carry out more thorough on-site inspections and demanding involvement in the regulatory process to soothe their jitters over Chinese manufacturers’ ability to properly build the complex vessels.

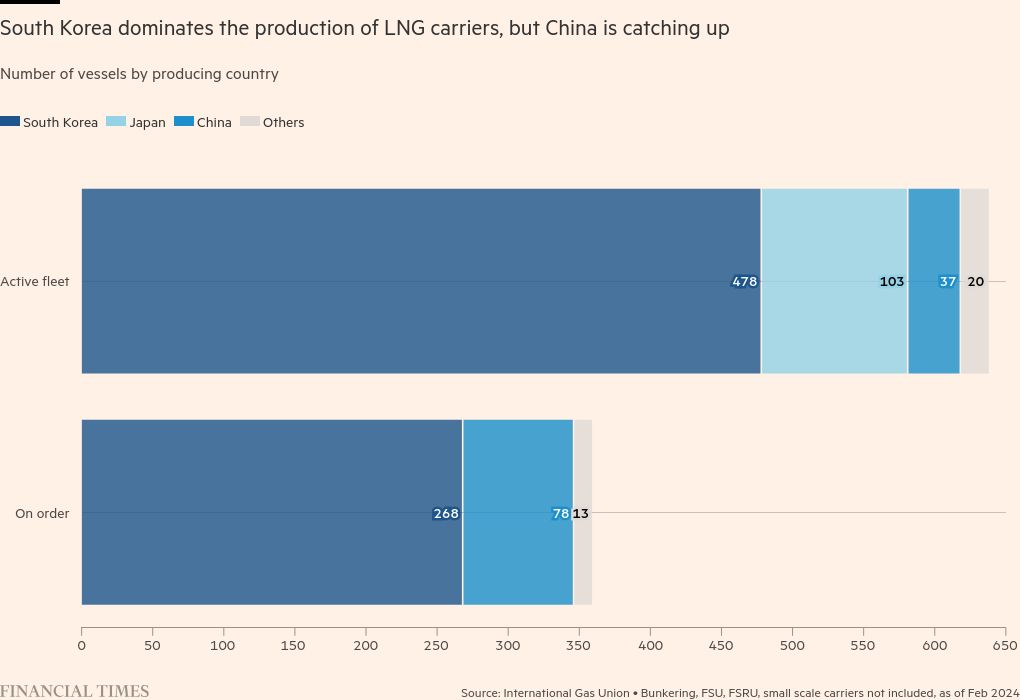

The trend highlights shipowners’ growing dependence on Chinese shipyards, despite their limited experience in building LNG vessels. Demand for the super-chilled fuel has left more established shipyards in South Korea unable to meet the need for new vessels, forcing the industry to seek alternatives.

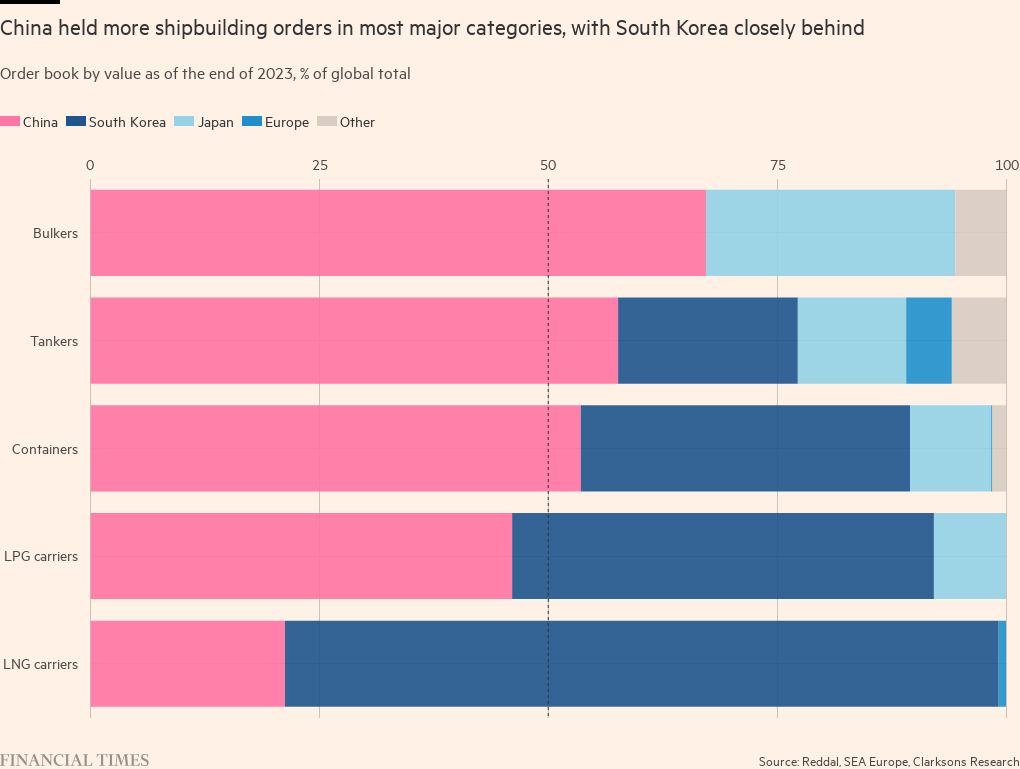

The rising demand comes despite the possibility of Washington imposing tariffs on China’s shipbuilders, which already dominate the production of container vessels and oil tankers.

“We’re in need of more ships than Korean shipyards can build [and] Chinese shipyards saw a great opportunity,” said Panos Mitrou, director of the gas business at Lloyd’s Register, one of the classification societies that regulates the construction of ships globally.

But the quality of LNG ships being built at Chinese shipyards is “a likely concern”, Mitrou said, meaning shipowners “believe in the right investment in supervision, in having the right teams there and making sure the quality is there”.

There is “huge demand for supervision teams” in Chinese shipyards, said Stephen Fewster, head of shipping finance at Dutch bank ING, which finances shipbuilding deals. “China doesn’t have experience of building LNG ships in the same way. The supervision the owner puts on the yard has to be that much more intense.”

The construction of LNG vessels, which transport gas liquefied by cooling it to below minus 160C, requires the installation of much more sophisticated containment and loading systems than those needed for other ships.

One shipowner said some customers preferred new vessels to be built in South Korea, despite its limited capacity and more expensive costs. “While a major [Chinese] shipbuilder like Hudong-Zhongua may now be on par with its Korean rivals, we are yet to finish quality due diligence on all the other Chinese shipyards,” the shipowner said. “There are lingering concerns about building the vessels in China.”

As well as sending more staff to construction sites, shipowners are also seeking contractual commitments from Chinese shipyards, according to two London-based lawyers who specialise in shipbuilding.

They added that ship buyers have used negotiations to request permission to attend meetings between shipyards and classification societies, as well as to be copied into emails between these groups.

Such demands have often been resisted by Chinese shipyards, who are in a stronger negotiating position when demand is exceeding capacity, the lawyers said.

The global LNG carrier fleet is expected to rise from 660 to 1,040 vessels by 2029, according to analysis group Drewry.

Countries from the US to those in the Middle East are boosting production of the gas to meet demand for alternatives to Russian gas and dirtier fossil fuels.

Although Chinese shipyards built just 6 per cent of the current fleet by volume, they are due to deliver over a fifth of the LNG carriers on order, according to industry group the International Gas Union.

Their increasing role in LNG carrier production mirrors China’s earlier takeover of other shipbuilding sectors, as its state-backed shipyards drew orders by undercutting rivals in South Korea and Japan on price. The average cost of building an LNG carrier in China is about $247mn, compared with $265mn in South Korea, according to Drewry.

Across all commercial ship types globally, Chinese shipyards built 46 per cent of the capacity delivered last year, according to the UN.

This growing dominance led the White House in April to announce an investigation into China’s “interventionist” and “unfair trade practices in shipbuilding”, prompting concerns that this could lead to US tariffs on Chinese-built ships.

But as China entered the more complex LNG shipbuilding industry, shipping groups warned they were struggling to find enough people to carry out the due diligence that they wanted on site.

The availability of LNG shipbuilding expertise “is awful”, said one shipping executive. “Finding the right people manning the supervision teams is a nightmare.”

He added that there was “a huge struggle between [the desire for] technical quality and commercial interests”.

“Whether we like it or not, these ships need to be delivered on time and they will be.”

Vanessa Tattersall, a partner at law firm HFW, said that although China was now delivering satisfactory LNG ships, similar situations had previously led to conflicts between shipbuilders and their customers.

“It will be interesting to see how many disputes we start seeing,” Tattersall said. “That’s my concern: are [Chinese shipyards] going to be able to cope with the amount of orders? Can they get these [LNG ships] out on time? Is any timing pressure that they’re under going to have an impact on quality?”