Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Turkey’s economic growth slowed to the weakest pace since the coronavirus crisis four years ago, underscoring how interest rates of 50 per cent are heaping pressure on businesses and households.

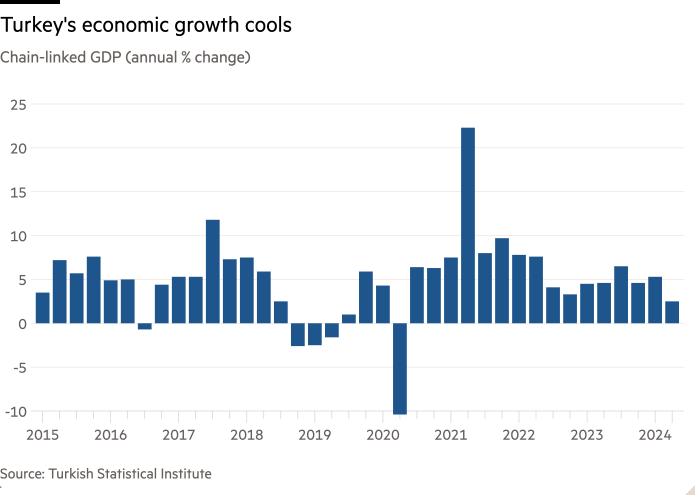

GDP increased at an annual rate of 2.5 per cent in the second quarter, Turkey’s statistical institute said on Monday, several percentage points lower than the downwardly revised 5.3 per cent in the first three months of this year.

Turkey’s decelerating growth underscores how policymakers’ programme to cool runaway inflation is exerting an increasingly heavy toll on major sectors across the country’s $1tn economy.

The annual rate of growth in the second quarter was the worst since a brief but steep contraction in mid-2020, at the height of the pandemic. It was also worse than the 3.4 per cent forecast by economists in a FactSet poll. Still, output inched up 0.1 per cent on a quarterly basis.

“Second-quarter GDP showed a significant loss of momentum,” said Hakan Kara, a former Turkish central bank chief economist. “Leading indicators suggest that lagged impact of monetary and credit tightening will be more visible in the second half of the year, but they do not point to a hard landing either.”

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan abandoned his failed policy of holding borrowing costs low despite blistering inflation after he was re-elected in May 2023. Turkey’s central bank, which is now run by a former Federal Reserve economist, followed up by boosting interest rates from 8.5 per cent to 50 per cent and vowing to keep monetary policy tight as long as necessary to tame the years-long inflation crisis.

There are now indications that high borrowing costs, combined with increases in petrol and VAT taxes and other fiscal tightening measures, are cascading across key industries. Manufacturing activity contracted for the fifth month in a row in August, an Istanbul Chamber of Industry survey released on Monday showed.

Meanwhile, previously red-hot consumer spending — one of the hallmarks of Turkey’s runway inflation — has been cooling in recent months. Car sales fell 16 per cent on an annual basis in July, according to Turkey’s Automotive Distributors’ and Mobility Association, while Turkish home appliances company Arçelik noted a “normalisation” in demand for white goods in the second quarter.

Policymakers and independent economists say cooling the overheating economy will be a pivotal step in bringing down inflation to the central bank’s 5 per cent target in the coming years.

The inflation picture has begun to improve, with annual consumer price growth coming in at 62 per cent in July after peaking above 85 per cent in late 2022. Turkish market participants expect inflation to hit 43 per cent by year-end before falling further in 2025, according to a central bank poll.

Mehmet Şimşek, the architect of the new economic programme, described Monday’s GDP data as a sign that growth had started to “stabilise”. He added: “We have left behind a difficult period in which we have significantly reduced vulnerabilities.”

However, economic officials privately concede that the recent progress on inflation has been the relatively easy part of the process because of last year’s high baseline in prices. The months ahead are likely to be more painful as businesses and consumers contend with high interest rates and slowing growth, a strong contrast to recent years when easy-money policies juiced up the economy.

“Domestic demand needs to weaken further and so policy will need to be kept tight for longer,” said William Jackson at Capital Economics in London. “Fiscal policy needs to do a lot of the work from here on, but monetary policy is also likely to remain restrictive.”

The tougher economic situation poses a conundrum for Erdoğan, who often touts Turkey’s years of fast economic growth as one of his key achievements since he rose to power at the turn of the millennium. Erdoğan has also used economic stimulus measures as a political tool, including ahead of the 2023 general election, which he won.

Erdoğan’s ruling Justice and Development party (AKP) sustained its biggest-ever defeat in March’s local elections as voters rebelled against the economic weakness. Polls show that the AKP’s popularity has continued to wane this summer as economic conditions have darkened for many Turks.