Radek Hábl quit his job in finance and set up a think-tank focusing on debt relief after his cousin asked him for the Czech equivalent of a €4,000 loan.

“I was ready to help her, but I first wanted to understand her problems,” Hábl said. “So we listed all her debts and loan sharks, and it showed not only that she was in a terrible spiral, but also the victim of a huge and unregulated debt business that we should never have allowed to develop.”

Under the Czech Republic’s post-Communist-era debt laws, loan sharks had powers to apply exorbitant late-payment penalties, force the freezing of debtors’ bank accounts or cut off their electricity without court rulings.

“The laws were written by a small group of lawyers who saw collecting unpaid debt as their quick way to become very very rich, even if this created a social crisis,” said Hábl, who set up the Institute for Debt Prevention and Resolution in 2019.

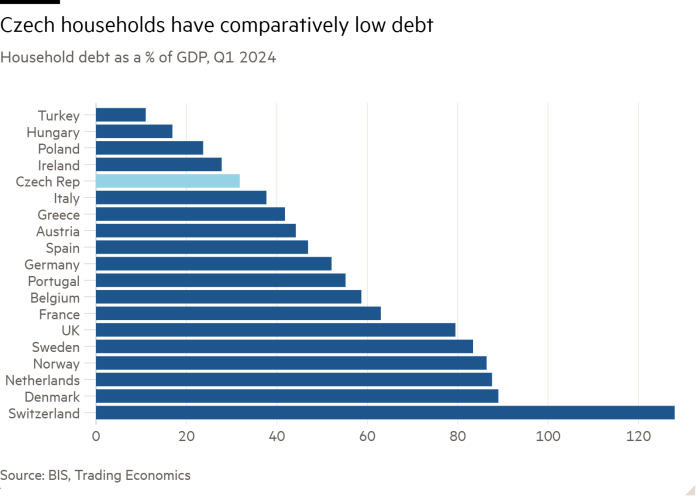

But on the back of campaigning by Hábl and other grassroots activists, lawmakers acted on a debt trap that once affected one in 10 Czechs. A series of measures since the turn of the decade has set the Czech Republic on course to move from being a nation with a big borrowing problem to become one of the least indebted countries in Europe.

Breaking the grip of personal debt has much broader benefits for society, from sustaining the labour market to ensuring children can finish schooling rather than being forced by their parents to leave early to earn money. The reforms have helped the central European country of 10.5mn people become a beacon of financial and economic equality.

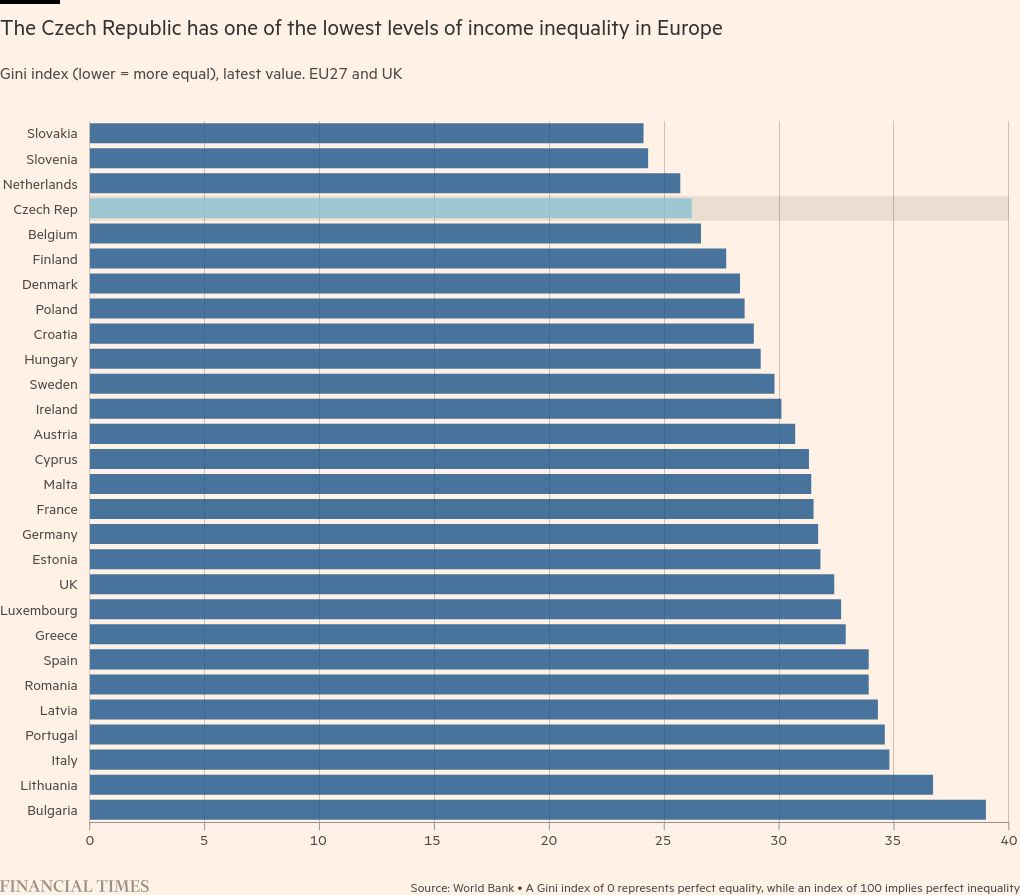

The Czech unemployment rate of 2.7 per cent is the lowest in the EU and the country’s poverty rate of 12 per cent is also the lowest — almost half the EU average of 21.4 per cent, according to Eurostat data on poverty risk and social exclusion.

The country also has one of Europe’s best records on inequality, as measured by the benchmark Gini coefficient.

Grassroots activists started by gathering data on repossession claims, which helped highlight the crisis and convince lawmakers to limit the powers of bailiffs.

While legislators tightened controls on these debt collectors, the Czech parliament separately agreed in 2021 to declare a “summer of mercy”, during which residents could pay off the principal on some state debt and in return get forgiven interest rate payments and other charges.

The finance ministry collected Kč400mn ($18mn) over three months of “mercy” and forgave Kč1.5bn of additional debt for public services ranging from court fees to municipal housing and waste collection taxes. With some adjustments, the mercy programme continues to be rolled out every year.

Separately, a new regulation approved by parliament in May this year reduces the period during which a debt relief claimant first has to pay back a minimum monthly amount after claiming insolvency.

Some Czech debt law was also changed to comply with EU legislation.

Still, some local economists warn that Eurostat is overstating the financial solidity of Czech society by calculating the poverty line at 60 per cent of its median income.

“Simply put, because we generally have low incomes, there are relatively few households that fall below that threshold,” said David Navrátil, head of research at Erste Group’s Czech subsidiary Česká Spořitelna.

Navrátil and others also note that the EU statistical office’s figures do not account for foreclosure proceedings and rely on surveys with a response rate of about 50 per cent. These most likely exclude many in abject poverty, from the homeless to members of largely segregated communities such as the country’s Roma population.

Eva Zamrazilová, deputy governor of the Czech central bank, wants more to be done to curb “predatory” non-bank intermediaries, as well as help borrowers understand their debt protection rights. “While the legislation may have improved, the financial literacy situation has not, despite the extensive efforts of various private and public sector institutions,” she said.

The measures have also not erased significant divergence between Czech regions, notably between the wealthy capital Prague and poorer surrounding cities such as Kladno.

Kladno’s coal and steel output, which helped power the country’s industrial revolution, has almost evaporated since the 1990s.

While factories and warehouses run by Lego, Amazon and two Czech bakery groups provide jobs, there are many shuttered shops on the high street, as well as several selling discount goods and secondhand clothing that suggest local consumers have little to spend. Some of Kladno’s 70,000 residents also live in derelict housing, including many Roma families.

For the past two years Sabina Kešelová, 24, who lives alongside seven other relatives in her parents’ home in Kladno, has struggled after taking a bank loan of Kč200,000 to pay for driving lessons and buy a secondhand car.

Soon after her purchase, she lost her factory job and had to fix the car’s engine, forcing her to halt loan repayments. Penalty and interest charges mean she now owes Kč500,000 and is considering declaring insolvency, because “my possibility of paying all this back keeps getting lower and lower”.

Kešelová is now seeking help from one of the country’s biggest charities, People in Need, which has a staff of 60 in Kladno and its surrounding Bohemia region, 12 of whom specialise in debt relief.

“The laws have got better and Czech society has become more open about discussing debt, which used to be seen as just shameful,” said Jana Odvárková, who works for People in Need in the city. “But when you look at our work here, it shows that EU statistics don’t tell the whole story and that we Czechs are still also perhaps number one at hiding some of our problems.”

Data visualisation by Keith Fray