Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Dubbed the Davos for central bankers, the annual Jackson Hole summit, which starts on Thursday, gathers the world’s top macroeconomists in the mountains of Wyoming to chew over monetary policy matters. It may not be as glamorous as its swanky Swiss counterpart, but as the discussions influence thinking around interest rate policy and inflation, it can be more consequential for the global economy.

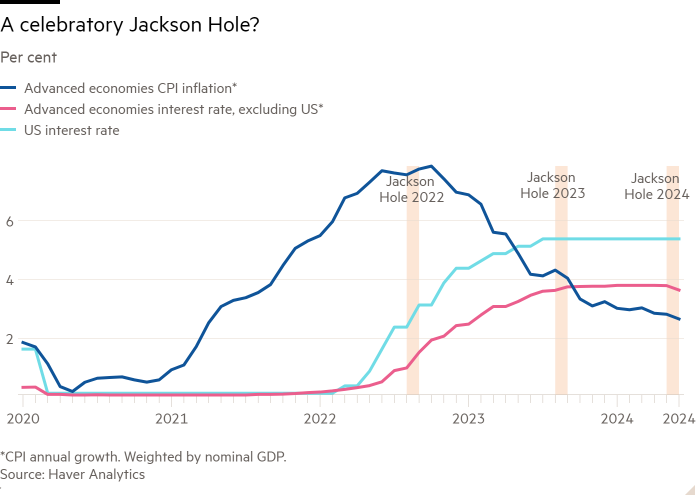

At last year’s symposium central bankers in advanced economies had made significant progress in battling inflation, but were far from certain they had vanquished the beast. This year, the tone will be different. Price growth is closer to inflation targets, and major central banks have already begun cutting rates, or are on the cusp of doing so. Price pressures are now less of a concern than support for slowing economies. All eyes are on US Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell’s speech on Friday, which may offer hints on America’s rate-cutting path.

Monetary policy wonks are not known for their partying, but the change in circumstances since the last summit warrants some celebration. Price growth has fallen without a significant rise in unemployment, so far. That is a rarity in rate-rising cycles. Central bankers may have got lucky: food and energy price pressures largely proved to be transitory, and labour-hoarding dynamics in the post-pandemic economy meant employers tended to restrain vacancies rather than jobs. Still, high rates helped anchor inflation expectations and curb demand.

It has not been a faultless rate-rising cycle, however. Central bankers were too slow to raise rates initially, and perhaps failed to realise that the feedback of higher rates into the real economy had weakened for several reasons during this cycle. Indeed, at this year’s summit — which will aptly ruminate on the “effectiveness and transmission of monetary policy” — central bankers ought to reflect on lessons learnt from the journey up, to manage the journey down.

What might they take away? First, central bankers need to better understand policy lags. The prevalence of fixed-rate mortgages in some economies meant that the impact of higher rates has come only with a long, and perhaps under-appreciated, delay. This should be kept in mind for rate cuts, too. Households that need to remortgage soon may still experience a notable tightening in their finances if they had locked in before rates shot up, even if rates are now coming down.

Second, rate-setters need to be more aware of on-the-ground economic dynamics that can interfere with assumed relationships. For example, the Phillips curve model — where lower inflation and higher unemployment accompany each other — has not been reliable in this cycle. That is partly due to quirks in the post-pandemic jobs market, such as labour hoarding, changing work preferences, and higher inactivity, which many monetary officials were too slow to grasp. Savings buffers and markets awash with liquidity also limited the effect of higher rates.

Third, effective communication is essential. Central bankers need to make clear that a “data-dependent” approach means they are focusing on a totality of data and not single data points, as Powell recently stated. Contradictory and sometimes unreliable economic data has made market expectations particularly volatile over this cycle. In future, placing more emphasis on a breadth of data and the overarching outlook may help policymakers guide markets better.

These lessons underscore the intricacy and, in turn, the limits of monetary policy. Central bankers have lessons to learn, but they cannot keep prices stable on their own. Keeping rates too high for too long eventually risks over-constraining the economy. Governments that have propped up inflation by running high deficits and failing to build enough homes also have their part to play.