Unlock the US Election Countdown newsletter for free

The stories that matter on money and politics in the race for the White House

Kamala Harris is aiming to increase the US corporate tax rate to 28 per cent if she wins the White House in November, a move designed to raise government revenues from corporate America that is likely to draw criticism from business.

Harris’s presidential campaign said on Monday that she planned to stick by a proposal put forward by President Joe Biden in recent years to bring the corporate tax rate up from 21 per cent to 28 per cent.

The statement comes as the vice-president fleshes out her economic plans ahead of formally becoming the Democratic presidential nominee at the party’s convention in Chicago this week.

Her tax plan for businesses contrasts sharply with that of her rival for the presidency, Republican candidate Donald Trump, who is proposing slashing the corporate tax rate to 15 per cent. Harris’s proposal would make the US’s corporate tax rate higher than the UK’s, at 25 per cent, and one of the highest among advanced economies.

“Unlike Donald Trump, whose extreme Project 2025 agenda would drive up the deficit, increase taxes on the middle class by $3,900, and send our economy spiralling into recession — her plan is a fiscally responsible way to put money back in the pockets of working people and ensure billionaires and big corporations pay their fair share,” a Harris campaign spokesperson said.

Last week, Harris said she would seek to cut taxes for the middle class including families with children, as well as boost incentives for first-time homebuyers and ban price-gouging by food and grocery companies, in a bid to show that she is tackling rampant cost-of-living concerns among voters.

An increase in the corporate tax rate could help increase revenue for the US government to spend on other programmes, but Harris did not specify how any extra money would be used.

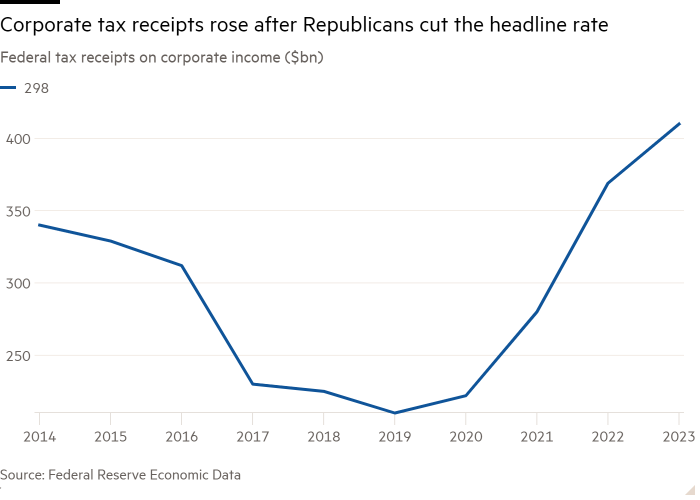

Her decision to stick to Biden’s goal of raising the corporate rate comes ahead of what is expected to be a fierce congressional battle next year over the expiration of sweeping tax cuts enacted by Republicans in 2017. Those cuts reduced the corporate tax rate to 21 per cent from a top rate of 35 per cent and the outcome of that negotiation will depend as much on control of Congress as it will on who wins the presidential election.

Despite the sharp fall in the headline rate after 2017, corporate tax receipts are higher now than they were at the higher rate, in part because of rising profits.

The Business Roundtable, a corporate lobby group, has estimated that Trump’s 2017 tax reform had resulted in $2.5tn of international earnings returning to the US. It has urged policymakers to retain a corporate income tax rate of “no more than 21 per cent”.

Unless Democrats win back the House of Representatives and keep control of the Senate, Harris will struggle to enact an increase in the corporate tax rate because of opposition from Republicans on Capitol Hill.