This article is an onsite version of our Unhedged newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every weekday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Good morning. Donald Trump has pledged to end the “persecution” of the cryptofinance industry, saying its rules should be “written by people who love [the] industry.” And so end Unhedged’s dreams of working at Trump’s SEC. Email us with consoling thoughts: [email protected] and [email protected].

Inflation is falling, the economy is strong, and the Fed needn’t rush

Wednesday’s FOMC meeting threatens to be pretty boring. No one thinks there will be a rate cut, and everyone thinks the Fed will open the door to a cut in September.

If the next CPI and PCE inflation readings are below the Fed’s 2 per cent target, we may indeed get a September cut. But it isn’t anything like a certainty, and it shouldn’t be. The risks of the Fed holding on a little longer are modest, because growth looks firm and steady in the face of the current level of rates.

Many observers, on Wall Street and beyond, are getting jumpy about the economy and worried that the Fed might break something. Unhedged thinks they need to calm down a bit.

Let’s go through the numbers.

Inflation

US inflation is just about at the Fed’s target. June core CPI — Unhedged’s preferred measure — was notably low, recording a 1 per cent month on month increase and a three month average of just below 2 per cent. The Fed’s preferred inflation measure — the personal consumption expenditure price index — is almost as good, but not quite. It came in slightly above expectations at 2.6 per cent annual growth, the same as May’s reading. But the pattern is similar. We don’t need things to get better, we just need the trend to hold.

Employment

Those who think rate cuts should kick off now are mostly worried about rising unemployment.

The headline unemployment rate has hit a 2 year high of 4.1 per cent. Though low by historical standards, the increase has been large enough that it almost triggers the Sahm rule, a recessionary gauge which suggests that a recession typically begins when the three month moving average unemployment is 0.5 percentage points higher than its low for the previous 12 months. The measure reached 0.43 percentage points in June.

But Claudia Sahm, inventor of the rule, is doubtful that its current reading indicates an impending recession. She told Unhedged:

Where we are right now, we are not necessarily on the cusp of a recession, but the 6-month chances of a recession are higher . . . What makes this all complicated is we have an expanding pool of labour supply, in part from immigrants, who make the labour market harder to measure. And it can take [some migrants] longer to find work. So you could expect the unemployment rate to drift back [once they do]. Immigration has increased at a speed and scale of disruption that is notable, which makes the employment numbers harder to read.

This cycle has been weird. The simple point to keep in mind is that unemployment around 4 per cent is very low. It is hard to imagine something awful happening to the economy when this many people have jobs.

Survey data

Both the recent GDP numbers and the early news from the Atlanta’s Fed GDPNow monitor suggest the overall growth is solid, and probably even above trend. All the same, the nervous nellies are nervous about squishy survey data.

Both the June ISM manufacturing and services surveys showed decreases in economic activity, including a surprising 12 per cent drop in the economic activity sub-index for services, into contraction territory. Manufacturing activity has contracted for 3 months in a row, and is doing so at an accelerating clip. Both surveys’ employment components are in contraction.

But the Fed has been particularly focused on non-housing services inflation, and they will not relax because of a single month’s ISM reading. The services component has been in expansion mode for 16 of the past 18 months. The price sub-indices are still in expansion for both manufacturing and services, too.

Is the consumer slowing down?

“US consumers show signs of flagging,” was the headline of an FT story over the weekend. The piece noted, variously, weakening consumer sentiment surveys; soft outlooks from consumer-product companies including Whirlpool, Lamb Weston, and UPS; and reports of discounting at retail chains.

These points are all true and all important. But these pullbacks look more like normalisation after periods of post-pandemic “revenge spending” than signs of widespread household belt-tightening. And the soft spots are matched with areas that look very robust.

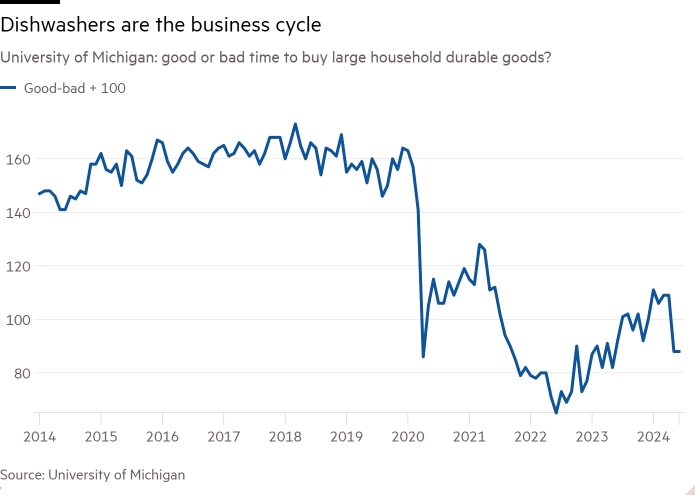

The latest reading of the University of Michigan consumer sentiment survey was indeed weak. But these readings have been hard to interpret since the pandemic. Over the past two years, there is a rising trend, but one marked by increasing volatility, with higher high and lower lows. The latest reading does not seem to break that pattern.

One key Michigan sub-survey asks consumers whether now would be a good time to make a major household purchase such as an appliance. Here the trend has clearly broken to the downside. An early indicator of weakness to come?

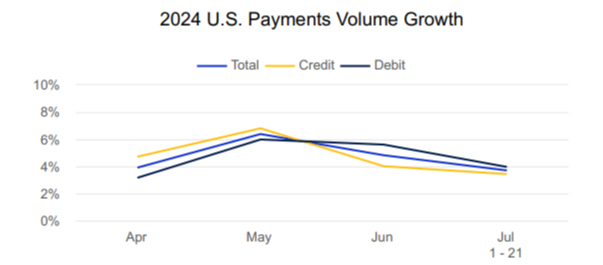

But the wobble in sentiment is not showing up in spending numbers. Real personal consumption expenditures growth continue to trend at about 2.5 per cent annually. Private data confirm that, while spending has slowed slightly, it is still growing nicely. Here is Visa’s charts of spending on their US networks:

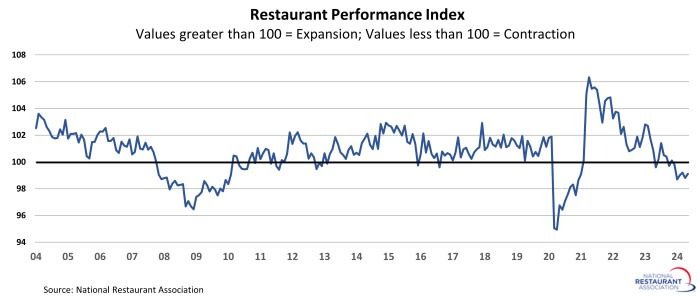

Last week in our discussion of Lamb Weston, we noted that there has been a slowdown in restaurant traffic and evidence of competitive discounting among fast-food chains. This shows up in the National Restaurant Association’s performance index, which has fallen into contraction:

This is striking, but may be less a signal of macroeconomic weakness than a natural response to the extraordinary restaurant boom of 2022 and 2023. It is hard to see a general consumer pullback when airline passenger volume looks like this:

While there have been a couple of disappointing reports from companies in the past few weeks, second-quarter earnings overall have been quite strong — S&P 500 companies have reported aggregate revenue growth of 5 per cent and earnings growth of almost 10 per cent, according to FactSet.

UPS’s bad quarter would normally be a bad omen, given that the company’s fortunes are generally tied to those of the overall economy. But the company’s problems are mostly about costs rather than demand. The US package volume trend has been improving for a year or so, and package volumes rose in the second quarter for the first time in nine quarters.

While some companies — Lamb Weston, for example — are facing tough pricing pressure, this is far from true across the board. Coca-Cola’s US business grew by 10 per cent in the quarter; almost all of that was down to price. While some housing-linked companies such as Whirlpool are struggling, not all of them are. The paint retailer Sherwin-Williams had a good quarter with higher volumes and prices. Branded consumer companies such as Colgate and Unilever reported good results; Colgate did cut some prices, but volumes rose sharply.

Financial conditions

In choosing its strategy for both communication and monetary policy, the Fed needs to consider the impact of financial conditions on growth. And while higher interest rates are clearly pinching certain sectors — housing and construction, mostly — financial conditions overall remain loose. Stocks are within a few percentage points of their all-time highs. Credit spreads are tight. Implied volatility is low. The economy overall does not look financially constrained.

In sum

The Fed does not appear to be in danger of making the classic mistake of keeping rates too high for too long. The economy remains notably strong, with more points of strength than weakness. Unemployment is low and companies are prospering. The Fed can afford to wait a little longer — longer even than September, perhaps — to be certain that inflation is defeated.

(Armstrong and Reiter)

One good read

An Olympic Zen master

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Swamp Notes — Expert insight on the intersection of money and power in US politics. Sign up here

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Vital news and views on what central banks are thinking, inflation, interest rates and money. Sign up here