When French swimming star Léon Marchand dives into the Olympic pool on Sunday, the 22-year-old will be favourite to win gold — and a crucial part of the host country’s effort to boost its medal haul.

After decades of stagnation in the bottom of the top-10 Olympic medal-winning countries, France began a push to improve the sporting prowess and mental resilience of its athletes ahead of the Games starting on Friday.

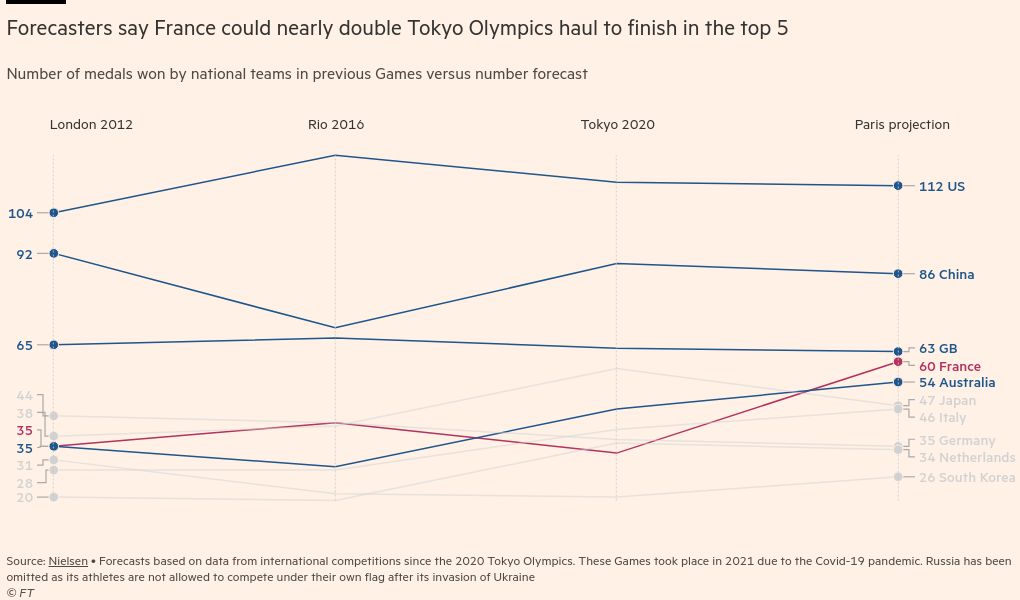

The cheerleader-in-chief, President Emmanuel Macron, set France a target to become a top-five medal-winning country. Experts and Macron himself admit this will be a tough challenge, given the resources and talent pool available to sporting leaders such as the US and China, and the head start the UK and Australia have achieved on investment and results.

But Macron said this week: “We have invested like never before in France over the past seven years . . . in our high-level athletes.” He added: “There will be a home-field advantage, so we have to be in the top five.”

Claude Onesta, a gruff but highly successful former coach of the men’s national handball team, is leading Macron’s mission. The Paris Games will be the first big test of his more top-down, national approach, inspired by the UK.

“Our old approach was invented in the 1970s out of a period of mediocrity, but had grown outdated. Other countries caught up while we were stuck,” Onesta told the Financial Times. “There was no time for diplomacy.”

Onesta turned to the UK as a model because it had greatly improved its Olympic results since the late 1990s, largely fuelled by a big cash infusion from National Lottery money. It hired the best coaches, built elite-level facilities and paid athletes to train.

Government agency UK Sport pushed fresh investment into sports with medal potential. Before the 2000 Sydney Games, UK Sport distributed £37mn to 13 sports. That figure leapt to £209mn before Beijing in 2008, while the number of sports receiving cash more than doubled.

The efforts paid off. A surge in podium finishes meant the UK finished third in the medals table when it hosted the Games in 2012.

After studying the UK model, and talking to France’s own federation heads about their gripes and desires, Onesta came away convinced that the French system needed a radical and rapid shake-up. Its federations were of uneven quality, he said. Complacency had set in because budgets did not change based on performance, and adoption of best practice on everything from nutrition to data analytics was patchy.

His idea was to create the Agence Nationale du Sport to centralise expertise and provide more rigorous oversight. The ANS, founded in 2019 and now led by Onesta, secured an extra €110mn on top of the usual state funding. It began to direct extra money to federations with the greatest medal potential and hold them accountable for athletes’ progress.

Controversially, Onesta also stopped allocating cash to federations relatively equally, although he did not dare go as far as the UK in targeting fewer sports.

“This would have been seen as decapitating the federations and provoked a revolt,” he said.

Instead, more money was given to 600 athletes on the ANS high-performance list, while dedicated experts supported their training. The strategy was inspired by the UK: France supported 5,500 athletes ahead of the 2012 Games, while Team GB backed about 1,200 but won far more medals.

French athletes to watch in the Paris Olympics

Léon Marchand

Competing in four events, the swimming prodigy is France’s great gold medal hope. He has been training at Arizona University where his coach is Bob Bowman, who taught 23-time gold medal winner Michael Phelps.

Teddy Riner

The judo wrestler has already won three Olympic golds. More than 2 metres tall and weighing about 140kg, Guadeloupe-born Riner, 35, towers over many competitors and has become an iconic figure in France, where there is keen interest in judo.

Clarisse Agbégnénou

The judo star from Rennes won gold at the Tokyo Games in 2021. Known off the tatami mat for her outspokenness about women’s issues, Agbégnénou, 31, had her first child two years ago and is seeking to show that mothers can return to the top level in sport.

Vahiné Fierro

The surfing champion from the tiny French Polynesian island of Ra’iātea grew up riding the waves. Fierro, 24, is one of the favourites in the surfing event, which is being held close to her island home in Tahiti on a legendary but difficult wave known as Teahupo’o.

Victor Wembanyama

The basketball player, 20, has been a sensation in the NBA where his freakish height (2.2 metres) and skilful co-ordination have wowed American fans. The French men’s basketball team hopes to eclipse the silver medal it won in Tokyo.

Sara Balzer

After winning a silver medal in Tokyo, the 29-year old fencer will compete in one team and two individual events. She is hitting her stride at the right time after strong performances in recent international competitions.

Onesta’s new approach ruffled feathers, especially with officials in larger federations who bristled under the agency’s tutelage.

Julien Issoulié, head of the swimming federation, was initially wary of ANS meddling, but came to appreciate the extra resources that allowed him to recruit a foreign coach, Jacco Verhaeren, who had driven the Australia team to Olympics glory.

“Bringing in an outsider with instant credibility helped end squabbling and rivalries between the different coaches and local clubs. It signalled we had big ambitions,” said Issoulié in an interview.

Swimming prodigy Marchand, who will compete in four Olympic events, will lead the charge. Born in Toulouse to parents who were competitive swimmers, Marchand is a product of France’s elite training system, which he joined aged nine. But his breakthrough came in 2021 when he went to the US to train under the former coach of swimming champion Michael Phelps.

Helped by new techniques, he shattered Phelps’s world record last year in the 400-metre individual medley, a feat he aims to repeat on Sunday.

Beyond the swimming pool, forecasters predict France can win in sports where it has historically been strong, such as fencing, handball, judo and rugby. Asked why France was so strong in fencing, Onesta said: “Well, we are the country of the Three Musketeers, after all.”

In judo, officials have drawn on ANS expertise in data and technology to better analyse athletes’ performance, and scope out opponents’ techniques via a purpose-built app.

While French judo’s biggest star, the three-time gold medal winner Teddy Riner, benefits from sponsorships, most of his teammates are amateurs with fewer resources, including five women seen as medal favourites. To help them earn enough to train, the ANS placed some in police and army jobs that offered flexibility.

Once-weaker sports, such as table tennis, taekwondo and triathlon, have newfound medal potential.

Surfing, an Olympic sport since 2021, used ANS support to build a training facility in Tahiti near the famous Teahupoʻo wave, where the competition will be held. Coaches moved to the distant island full time to allow roughly 50 surfers aiming for the Games to train on the powerful wave known for its huge tubes.

Four surfers qualified for the Games, including the 24-year-old French Polynesian Vahiné Fierro, who could win gold.

“In our sport there is a lot we cannot master, like the weather conditions and the wave, but we have improved everything we have control over,” said Stéphane Corbinien, who heads the surfing federation. “We will see soon whether the years of preparation pay off.”