Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Levels of hunger are set to remain “shamefully” high, UN officials said as the multilateral organisation published a report that predicts almost 600mn people will be undernourished by 2030.

The report, published on Wednesday, came as senior UN officials called on donor governments to rethink prioritising national interests over foreign aid.

While the 582mn figure is lower than current levels, it is a long way off the target of eradicating hunger by 2030, set by the 191 member states that make up the UN under the multilateral organisation’s sustainable development goals in 2015.

Half of the number will be in Africa, according to the UN food, agriculture and health agencies, which together authored the report. Most of the remainder of people unable to consume enough calories to maintain a healthy lifestyle reside in Asia.

The report follows the publication of UN estimates, which show official development assistance to developing countries is going down.

According to the UN report, only about a quarter of that assistance — $77bn — went to improving food security and nutrition in 2021, the most recent year for which data is available.

Alvaro Lario, president of the UN’s International Fund of Agricultural Development (IFAD), said the political landscape was placing foreign aid and multilateralism “more and more into question” as national interests were being brought to the fore.

“That clearly diverts the focus on trying to address and join forces on tackling a global issue, which is food insecurity,” Lario told the Financial Times.

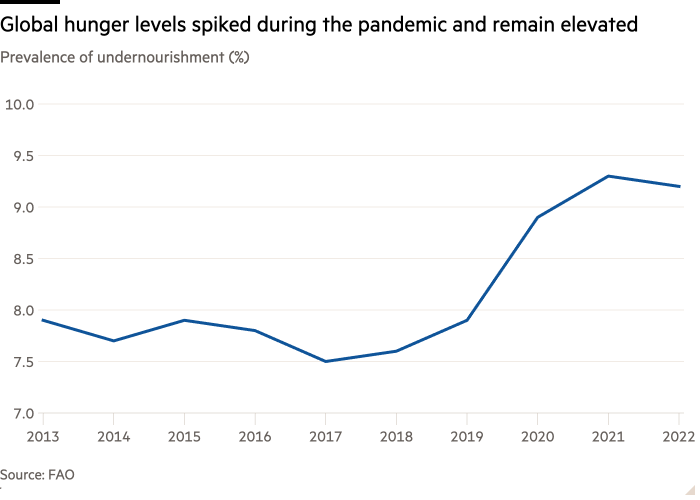

Rates of hunger jumped in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and have since failed to come back down as UN agencies expected. Last year, between 713mn and 757mn people were facing hunger, according to the UN report.

While the number of people without enough to eat has declined in Latin America and the Caribbean and stayed relatively unchanged in Asia, it is continuing to rise in Africa, said the report. There, one in five people faced hunger last year.

Overall, a higher portion of people are undernourished today than 10 years ago, according to UN estimates. This leaves the world on course to have a projected 582mn people chronically undernourished by the end of the decade.

Shock events, such as the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, have helped to drive up food insecurity. Before the pandemic struck, the projection for 2030 was for 451.8mn people to be undernourished.

However, UN officials believe the goal of zero hunger by 2030 could have been achieved with more funding from donor governments and better co-ordination.

“Not only the donors, but our agencies should feel ashamed because it’s not only the money, it’s also how we implement it,” said Maximo Torero, chief economist at the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization. “There is a co-ordination failure. There is a lot of inefficiencies in the way the resources are being used.”

Often foreign aid focuses on emergency assistance, but more funds need to go to agriculture — “the root causes” of food insecurity, said Lario. “In five years, unless we invest now, we’ll be in the same situation,” he said.

In particular, small-scale farmers in poor countries need more financing to adapt to climate change.

“Why today [does] only 3 per cent of climate financing goes to agriculture and agri food systems?” said Torero. At successive COP climate conferences, agriculture has been portrayed as “the bad sector”, he said. “They forget the fact that agriculture is the one that provides food to people.”