For the past month, Philippine and Chinese diplomats have been working overtime. After the countries’ most violent clash yet in the South China Sea, officials on both sides have been trying to de-escalate a confrontation that threatens to spiral into open conflict.

Those efforts have led to agreement to open new communication channels for maritime incidents, and a temporary arrangement for the Philippines’ resupply missions to its military outpost on Second Thomas Shoal, a submerged reef in the disputed waters.

But lowering tensions will be difficult. Earlier attempts at compromise over the past year fell apart within weeks, and Beijing and Manila started disagreeing over the terms of their latest arrangement less than a day after it was announced.

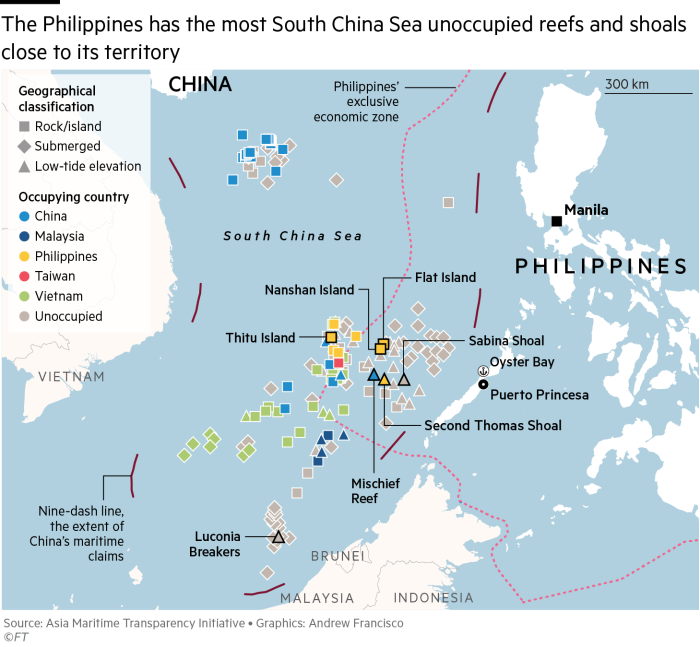

At the same time, the countries’ coast guards have become embroiled in another stand-off. On July 3, a day after the latest round of diplomatic talks, China’s largest coast guard ship, a 165-metre vessel Philippine officials have nicknamed The Monster, anchored at Sabina Shoal, a reef about 65km east of Second Thomas Shoal.

Its mission is to intimidate a much smaller counterpart: the Teresa Magbanua, which the Philippine coast guard deployed to the shoal in April after the discovery of heaps of crushed coral sparked suspicion of a new Chinese island-building attempt.

“We urge the Philippines to immediately evacuate personnel and ships and not go further down the wrong path,” Chinese defence ministry spokesperson Zhang Xiaogang warned on July 12, charging that Manila’s presence “seriously violated China’s sovereignty . . . created new tensions in the South China Sea, and further undermined regional peace and stability”.

Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr said in his state of the nation address on Monday that his country was continuously trying to find ways to de-escalate tensions in contested waters. But he added: “The Philippines cannot yield, the Philippines cannot waver.”

Sabina Shoal seems an even more unlikely place to fight over than Second Thomas Shoal. The latter has served as a critical military outpost for the Philippines since its navy purposely grounded a decommissioned US warship in 1999. A small group of Marines stationed there asserts Manila’s jurisdiction and keeps track of ever-more frequent Chinese incursions.

Since early 2023, China’s coast guard has steadily stepped up the level of force to disrupt Philippine resupply missions to the shoal, including temporarily blinding Philippine sailors with lasers, ramming vessels and spraying them with water cannon.

In a skirmish in June, Chinese forces punctured the Philippine Navy’s rigid inflatable boats, towed vessels away, boarded others and confiscated guns — actions that injured one Philippine soldier, according to Manila, and which international law experts warned came dangerously close to an act of war.

Greg Poling, director of the Southeast Asia Program and the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) at CSIS, the Washington think-tank, said the risk of escalation at Sabina was far less than at Second Thomas.

“Sabina Shoal falls into a second category, which is everything else around the Philippines’ islands, where Manila is trying to maintain a presence, increase patrols, to show that it’s in control of its waters,” Poling said. “If the situation there develops into something, it would be irrational. But a lot of what happens in the South China Sea is irrational.”

For defence experts in Manila, the situation looks very different. “You pass by Sabina Shoal on the way to Ayungin,” said Gen Emmanuel Bautista, former chief of staff of the armed forces of the Philippines, referring to Second Thomas Shoal by its Philippine name. “So if China seized Sabina, they would practically be cutting off Ayungin Shoal.”

With control of Sabina, China would be close to access routes to other features Manila controls, such as Nanshan and Flat Island, and “creeping closer” to Palawan, a province in the Philippines.

“It would be on a potential path of an invasion from Mischief Reef,” Bautista said, referring to one of the China-built artificial islands from which Beijing polices its claim over almost the entire South China Sea.

Despite Manila’s initial fears, many officials now believe that the traces of tampering with the coral reef are unlikely to point to another reclamation attempt. Satellite imagery shows no evidence of recent new Chinese island building, according to AMTI.

Beijing has little need for new outposts, with bases on artificial islands and a huge fleet of coast guard and maritime militia vessels allowing it to interfere in the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone within hours, one Philippine security official said.

Other claimants face similar pressure. According to AMTI statistics, the area most frequently patrolled by Chinese coast guard ships was Malaysia’s Luconia Shoals, more often even than Second Thomas Shoal.

“Their operating distance has become so much shorter, they can stop for resupply and stay out longer,” said Thomas Daniel, senior fellow at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies in Kuala Lumpur. “They also have maritime surveillance aircraft taking off from Fiery Cross,” he added, referring to another Chinese artificial island.

But the Philippines faces a geographic challenge absent for other South China Sea claimants. Vietnam controls a large number of land features that it occupied in the 1980s, long before China created its formidable maritime force, that are above water even at high tide. There are few unoccupied reefs between these land features and Vietnam’s coast.

The Philippines’ exclusive economic zone, by contrast, is studded with unoccupied reefs and low-tide elevations that Manila fears China could seize to enforce ever more of its territorial claims.

But Manila’s position is improving. Systems provided by the US, Japan and Canada allow it to track most Chinese coast guard and maritime militia vessels.

Moreover, Manila built a small harbour on Thitu Island in the Spratlys two years ago and established a naval detachment at Oyster Bay, on the west coast of Palawan. These two footholds drastically shorten the distance for patrols, which previously had to sail hundreds of kilometres from Puerto Princesa on Palawan’s east coast to reach the South China Sea.

“Now the Philippines is moving to a place where, much like Vietnam, it can have a small but capable force to patrol right at the scene of the action,” Poling said.

For de-escalating tensions with China though, that prospect may not bode well.

Diplomats in the region said the latest round of diplomacy was consistent with Beijing’s long-running pattern of engaging in consultations with rival claimants, which had yielded no real results over more than 20 years. “There are signs they are trying to press for some agreement, but no signs of compromise,” said a foreign diplomat in Manila.

The Philippine security official said that, despite efforts to improve communication, Manila would not back down. “If China does not understand that, no hotline will help,” he said.

Additional reporting by Anantha Lakshmi in Jakarta